Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsA journey through time and spices

A young writer’s new book explores how the spice trade shaped Indonesia’s social and political structure.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

Spices are a big part of Indonesia’s identity.

During the archipelago’s European colonial period, they were the driving force of colonization. Hundreds of years before that, spices from Indonesia were one of the main commodities Chinese and Arab traders sold to Europeans. They not only gave flavor to dishes but also preserved food, something that was crucial during the middle ages, as Europe was regularly ravaged by war instigated by its ruling classes.

Europeans dreamed of direct access to spices and sent expeditions to find their source. In 1512, the Portuguese became the first European explorers to reach the islands of Molucca, now known as Maluku, which boasted an abundance of rare spices.

Soon after the Portuguese, the Spanish arrived in Maluku in 1521 by crossing the Pacific. The two nations, which had conquered many parts of the world, fought for dominance over the islands.

By the end of the 16th century, explorers from other European nations had begun to hoist their flags on the islands of what is now Indonesia. Then began the era of Dutch and British colonization. The Dutch East Indies Company (VOC) and the British East India Company (EIC) imposed forced labor on native populations for spice production.

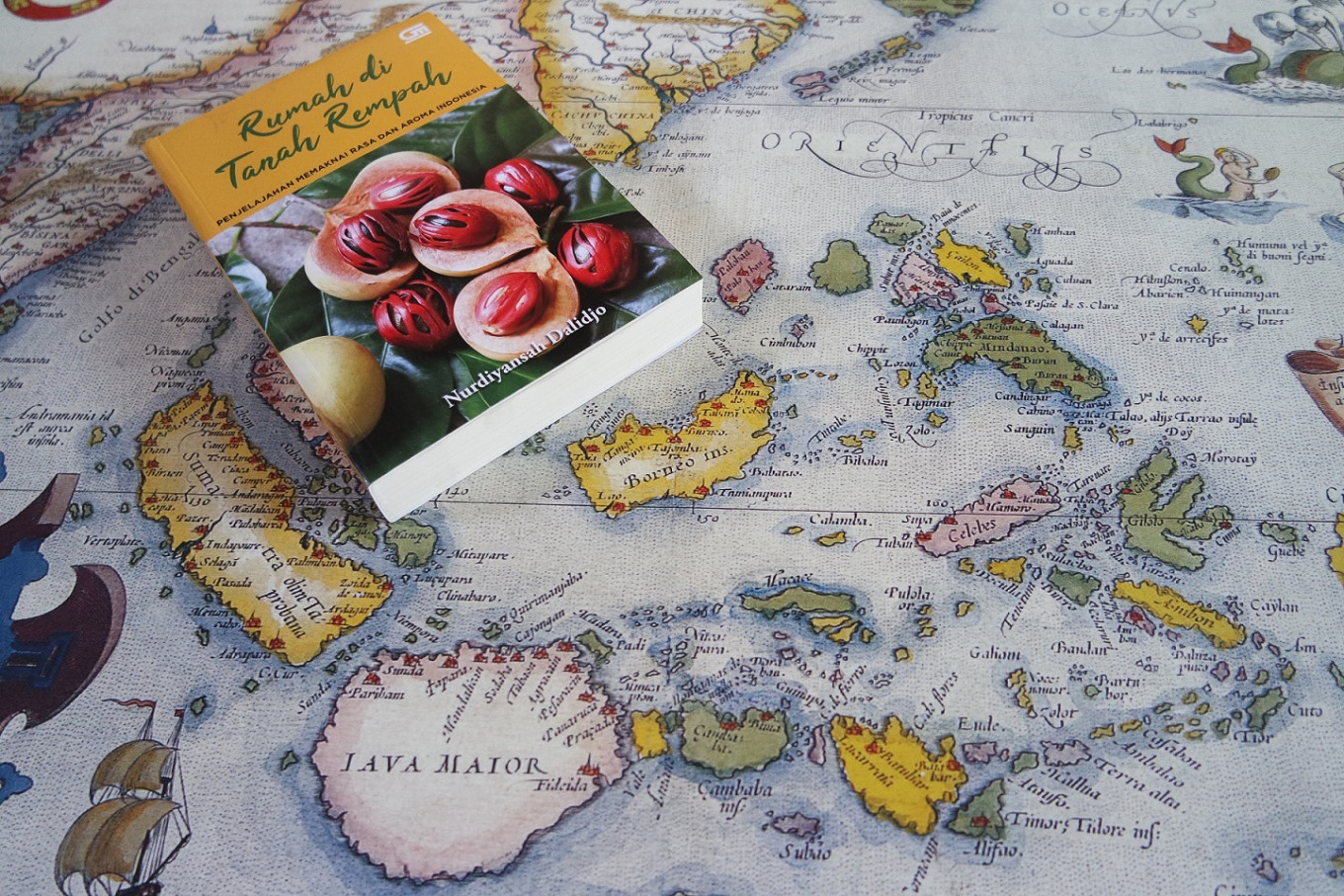

This spice-driven history of colonization is what pushed 33-year-old interdisciplinary writer, researcher and journalist Nurdiyansah “Diyan” Dalidjo to write a travelogue titled Rumah di Tanah Rempah (Home in the Land of Spices).

Nurdiyansah Dalidjo. (Nurdiyansah Dalidjo/-)Spices have been a big part of Diyan’s life since he was a boy. He grew up with a single mother who would cook him his meals and then have conversations with him while they ate.

Diyan became curious about the role of spices in Indonesia’s history.

In history classes at school, he was told to memorize historical events and figures without context, and he wondered how they were connected to the spices that brought Europeans to the islands that would constitute Indonesia.

He believed that behind the iconic foods and fragrant spices, every region of Indonesia had a history, from the colonial era to social revolutions.

“As someone who grew up during the New Order era, I did not understand why spices were so valuable that they caused Indonesia to be colonized and led the people into slavery and other human rights violations,” said Diyan, who also blogs about human rights and was once a journalist for Indonesian feminist publication Jurnal Perempuan (Women’s Journal).

Old gold: Nutmeg was once a prized commodity among European colonizers. (Nurdiyansah Dalidjo/-)Each chapter of the book covers an island of Indonesia and each subsection tells a story from the 21 different regions that Diyan visited, from Aceh to Ambon.

Diyan independently traveled and collected the data for his book from 2014 to 2018.

The book explores sensitive and provocative subjects such as the rise and fall of communism and how Soeharto’s New Order started a new revolution, but Diyan focuses his narrative on the issue of how human rights violations and social gaps are present in historical events and how they reflect parts of modern Indonesia.

Diyan titled one of the travel stories in the book Tahun tanpa Pempek (a year without fish cakes). It explores the large role of South Sulawesi in the creation of the Republic of Indonesia and the historical events transpired there.

While in Jambi, Diyan stopped by the Muarojambi Temple Complex, a place that, according to a Chinese Buddhist monk named I-Tsing who visited Sumatra in 671 AD, was once the world’s greatest center of Buddhist learning after Nalanda University in India.

The complex stretches 30 square kilometers and has numerous temples, remnants of the once-great kingdom of Srivijaya.

Srivijaya’s rule influenced most of the land and maritime areas of Sumatra, Java, the Malay Peninsula and its surroundings. It was the Musi River that made Palembang, a city famous for its pempek, the heart of international trade in the kingdom.

In South Sumatra, Diyan learned about the impact that the kingdom of Srivijaya had on Indonesian culture. The Malay language or Bahasa Melayu was the main language of the empire. The language was used for trade along the Strait of Malacca, the Sunda Strait and on the beaches of Sumatra and Java.

Indonesia’s national language is essentially a dialect of Malay, and Srivijaya played a big role in its transmission. The Musi River contributed to this historical change, making South Sulawesi the center of international trade in the area at the time.

Centuries later, the river became a part of another, bloodier historical event.

Standing on the small island of Kemaro, located on the banks of the Musi River, Diyan pictures how the island was a silent witness to the systematic killing of Indonesian Communist Party (PKI) members in 1965 and 1966.

“I would like to tell this story in a ‘they said’ quote, because it is believed that in 1965 to 1966, Kemaro Island was the place where the bodies of members and sympathizers of the PKI were thrown away or buried,” Diyan said.

According to Diyan, the idea of rotting bodies and blood in the river caused people in the area to avoid their fish-based iconic dish, making the period from 1965 to 1966 the year without pempek.

“This shows how history is not binary, and just like Indonesia’s culture, it is very diverse,” Diyan added.

With a master’s degree in tourism management and a bachelor’s degree in journalism, Diyan has a passion for travel and a knack for storytelling. He said he had written several scholarly travel books, noting that such books did not tend to appeal to the general public because they were boring to read and write, so the books only circulated in the academic community.

Rumah di Tanah Rempah is Diyan’s second published travelogue. His first was titled Porn(O) Tour: Sisi Lain Sebuah Perjalanan (Porn(O) Tour: The Other Side of Travel). In this book, he examined the disruptive effects of tourism on popular sites.

“The drive that made me write […] was my emotional ambition to travel all over Indonesia,” Diyan said.

The writer is an intern at The Jakarta Post.