Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsHow we can do better: No rose-tinted glasses: Inside Indonesia's human rights organizations

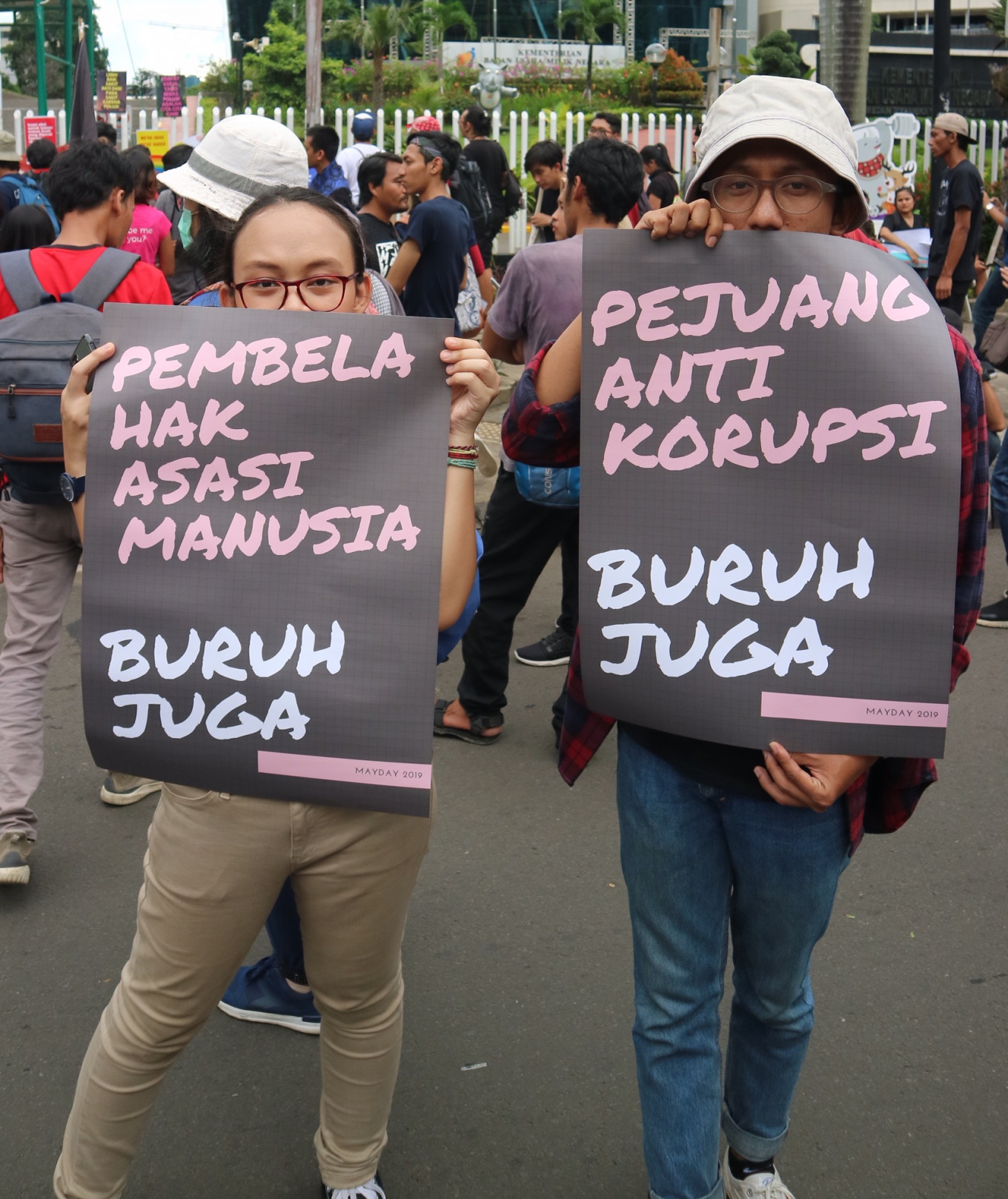

Working at a human rights organization may seem like a lifelong career in fighting for the common good of all people, but the reality is far from the ideal, as three activists recount their personal experiences on the job.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

“How we can do better” is a new column that takes an insider’s look at various sectors and how they could improve. In this second installment, we delve into Indonesia’s NGO sector.

For many victims of state crimes, human rights activists may represent their chance for making a final stab at justice and restitution, but life as a rights activist is a heavy one. As they fight against dirty donor politics, internal squabbles and financial woes, their stalwart dedication to humanity is their one saving grace.

Overworked, ridiculed and battling an enemy too distant to care, the misadventures experienced by human rights activists in Indonesia could fill a thick tome. They face death threats even as they confront the seediest sides of post-New Order Indonesia on a daily basis. But for many, it is a cross they have chosen bear out of a profound sense of duty.

"Personally, I feel like we're maintaining a common dream," said Esther (not her real name), a 29-year-old human rights activist. "In spite of everything, here we have a sense of hope."

Esther's story is a familiar one among activists her age. She belongs to a generation of post-2010 idealists who emerged after the elation of reformasi had subsided and frustration at the slow pace of democratization had already set in.

There was an atmosphere of hope, she recalled, but also uncertainty. Fresh out of law school, Esther applied for a research job at one of the country's top anticorruption watchdogs, where she has worked for the past eight years.

She possesses a steeliness when speaking about her chosen field. Even so, she has no illusions about the challenges her peers face. Forget the external threat that human rights violators pose: Today's activists must contend with a convoluted internal world of donor politics, an infamous toxic work environment and stuttering attempts at regeneration.

Win the battle, lose the war

Nisrina Nadhifah is considered somewhat of an old-timer in the nongovernmental organization (NGO) sector, despite her relatively young age of just 26. She has volunteered with various national and international NGOs for over a decade since her early teens. She has seen it all and she speaks with resigned weariness about donor politics, a universal issue that is also dogging Indonesian NGOs.

"We live under a regime of donors," Nisrina said. "There are [many] organizations with decades of experience and deep local insight, but when they meet foreign donors who hold all the funding, they have to follow suit. Many have to lower their standards to comply with the donors."

Nisrina observed that the shift to donor-driven funding happened after the birth of the Reform movement in 1998 and in the aftermath of the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake and tsunami in Aceh. Both were momentous times when large amounts of aid and social work were in sudden demand, and community-run organizations were forced to expand at an unnatural rate. The two events also positioned Indonesia as a young, fragile democracy in need of international aid, and donor funds began pouring in.

Read also: COVID-19 crisis erodes women’s rights in Indonesia: Activists

The unequal relationship between donors and NGOs, however, means that rather than executing actions that directly benefit civil society, many organizations have been distracted by endless programs that follow the whims of foreign donors. Such programs may look grand on paper, but often have limited long-term impacts for the people they are supposed to help.

Esther lamented the decline of activists as mere "proposal crafters", while Nisrina felt this had led to creating a "toxic culture” at organizations that had become reactive and unfocused.

"We are slowly forgetting the big picture," Nisrina criticized. "NGOs have become better at executing programs, but worse at planning and management."

"Donor politics is a dirty game," said Esther.

"[Donors] fund NGOs and governments alike. So when we're advocating against something, the donors are actually moderating the conflict, all the while really serving the purposes of their home countries. NGOs aren't free to decide their [own] moves. This conflict of interest often leads NGOs to soften their approach," she added.

Esther and Nisrina’s observations paint human rights organizations as reluctant players in a sector with unsustainable demand and a creaking, ponderous supply chain. Activists might grumble in private about the rules and wayward programs imposed by certain donors, but dig a little deeper and they will begrudgingly admit that such donors are, at the very least, a necessary evil.

Understandably, many NGOs are struggling to keep up amid the precariously limited resources and high demand for immediate action. Whether through careless management or sheer overload, human rights organizations have become notorious for their toxic work environment. A culture of overwork, low salaries, backdoor political gamesmanship and lack of work-life balance reign supreme.

"On paper, we work 9 to 5, but in reality it's more like 9 to 9," joked 28-year-old Nanda (not his real name). "If a client calls us at 10 p.m., it's an emergency. We can't just say we're out of office."

Esther and Nisrina both recount similar experiences of expectations that activists be on call 24/7 and treat every situation as urgent. For Nanda, a newlywed who has worked almost a decade in advocating for human rights, this unspoken culture has inexorably changed his personal life.

"We're afraid of planning something far in advance," he said. "For example, I can't say that next month I'm going to take a leave of absence or go on vacation. If I take a day off, it's a spur-of-the-moment thing. Everything is, except for work."

Worryingly, this situation is treated as the norm. "We normalize this simply because we work at NGOs," said Esther. "It's as if this is an acceptable risk when we're fighting for the common good, but this culture is exploitative. Many activists risk their lives in the field without overtime pay, transport reimbursements or operational support."

Any pushback is often been met with stiff resistance from management. "There's a feudalistic narrative that back in the day, activists were so dedicated they even lived in the office," Esther continued. "And older activists are happy to repeat this anytime someone protests about overwork. Asking for more reasonable working hours is considered as a sign of a lack of dedication."

The old guard

Esther's critique touches on a sensitive subject among today's activists: the role of senior employees at human rights NGOs, specifically those of the generation that flourished during the 1998 crises.

"NGOs definitely have a seniority problem," Nanda said. "And there's a lot of ‘shadow’ seniors [...] former activists or peers of board members and they think they know everything. This makes it difficult for younger activists to share their insight and ideas. Things only start moving once the seniors think that it's time."

This disproportionate loyalty toward a declining generation of activists, coupled with a dated, romanticized view of social work, has resulted in bleak morale.

Read also: Human rights deteriorated in Indonesia in 2020: Amnesty

"The line between the personal and professional is blurred," Nanda said. "The closer you are personally with the bosses, the better your life is. And that means it's difficult for [other] people to call you out when you make a legitimate mistake."

Although he declines to name names, he claims that many activists have gotten away with allegations of sexual assault, conflicts of interest and professional neglect because of their close ties with a cabal of senior activists. "They have a circle of friends that shield them from [such] allegations.”

“Many cases got lost in a fog of denial or half-measures that were taken in response. Obviously, no justice was truly served," he added.

As younger activists struggled to reckon with the questionable leadership of their seniors, the internal NGO culture apparently shifted to a more sinister direction.

"After 2014, we began seeing an influx of ambitious activists who saw NGOs as a stepping stone to politics. They would use their past [role] as an activist to convince people that they will fight for the common good. But in reality, these opportunists only bog down any attempt at meaningful change," said Esther.

After these “freeloaders” leave the NGOs, what's left is a cast of misfits: People like Esther who privately confide their fears that their skill set is unusable in any other sector; people like Nisrina and Nanda whose patience is only matched by their headstrong, genuine dedication to human rights; and many senior activists who haven't been picked to join their peers in political parties or political pressure groups.

Change is coming

"We're sliding further into donor dependency," Nisrina sighed. "When I look at feminist and LGBT collectives around the world, they've taken to more creative means to fund themselves. Some open ad agencies, others run salons, minimarkets and other small businesses to fund their activism."

The strategy isn't unthinkable in Indonesia, where it would have an unexpected, added advantage.

"The opposition has always painted us as the lackeys of a shadowy foreign power. It's not significant, but it's enough to foster distrust and dent our credibility to the public," Esther observed. Becoming financially independent and transparent would go some way toward restoring public trust in NGOs, she added.

Read also: Speaking out: Addressing past human rights violations in Aceh and Timor-Leste

According to Nanda, NGOs must also be proactive in breaking up the cumbersome bloc of aging activists. "Younger activists and people on the ground should be asked about the reality on the field and encouraged to suggest solutions, then we can collaborate with others to implement [these solutions]," he said. Simply put, it's high time that NGOs trusted their own people.

Ultimately, these innate problems can be fixed only through structural change. If these internal flaws are to be remedied, then NGOs must fundamentally rethink the way they're funded, managed and organized. Tall order, then, for a sector famously slow to adapt and stubbornly reluctant to change.

Many younger activists have allegedly found the going too rough and fallen by the wayside, but people like Nisrina are here to stay. Having handled some of the country's toughest human rights cases, her dedication remains as strong as ever.

"It may sound cliché, but this field makes me feel like I can truly be myself. I don't feel like I'm [...] a robot. I'm human and helping other humans. Somebody has to do it," she said. (*)