Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsOei Hiem Hwie: The guardian of Pramoedya Ananta Toer’s banned literary tetralogy

Oei Hiem Hwie quietly smuggled the Buru Quartet, a series of novels banned under Soeharto’s rule, past the regime’s ideological enforcers.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

T

his article is the first of a two-part story on Oei Hiem Hwie, a former political prisoner and a close friend of author Pramoedya Ananta Noer who today manages a library called Medayu Agung in Surabaya.

Oei Hiem Hwie quietly smuggled the Buru Quartet, a series of novels banned under Soeharto’s rule, past the regime’s ideological enforcers.

Without his courage, one of the novels, Bumi Manusia (This Earth of Mankind), which explores the colonial period's sociopolitical issues, would have been unknown to modern audiences. The book, which remains one of the iconic author’s most recognized works, was banned by the Attorney General’s Office (AGO) in 1981, allegedly because it promoted Marxist-Leninist doctrines and communism.

On Nov. 26, 1970, Hwie and hundreds of other political prisoners arrived on the island of Buru in Maluku. There, Hwie was detained for 13 years without a trial by Soeharto's New Order government.

Hwie was imprisoned after the country’s 1965 massacre of alleged communist sympathizers. Before ending up on Buru, he had moved from one prison to another. He was arrested in Malang, East Java, and was first sent to Lowokwaru Prison in late 1965. He was then transferred to Koblen Penitentary, an institution for political prisoners in Surabaya. A few months later, he and hundreds of others were transferred to Nusa Kambangan, where Hwie spent five years before finally ending up on Buru.

The New Order was meticulous about what it called “putting things in order”, dealing with so-called “leftists”. People who were labeled as such had only three possibilities: imprisonment, exile or execution. According to Pramoedya Ananta Toer, the events of 1965 claimed at least 2.5 million lives. "And [former Indonesian Military (TNI) leader] Sarwo Edhi said those numbers proudly," Pramoedya noted in the 2001 film Mass Grave by Lexy Rambadeta.

Hwie's name was on the list of leftists. This was because of his close relationship with former president Sukarno during his time as a journalist at the Trompet Masjarakat newspaper. He was labeled a “Sukarnoist”, and such sympathies were considered counter to the political principles of the New Order.

"I couldn't find a reason to deny the accusation that I was an admirer of Sukarno. I indeed idolize Sukarno. As a president he was very close to his people," Oei Hiem Hwie told The Jakarta Post on Sept. 11.

"There is one memory that will always remain with me: being given a watch by the former president. 'Hwie, you are a journalist. You must have style. How come a journalist doesn't have a watch?' Then, he took off his watch. I still have that watch,” he said.

In the Buru internment camp, the days were bleak. Having been denied a trial, Hwie did not know how long he would languish on the solitary island. He formed friendships with prisoners with the same fate. One was Pramoedya Ananta Toer, a writer whose work was later translated into 42 languages. Hwie met Pram – Pramoedya's nickname – through his work on the island as a mail courier. Through Hwie, Pram discussed the works he was writing in exile with other intellectual figures.

Hesri Setiawan, Oey Hai Djoen, Sartono and other prominent thinkers were often given copies of Pram's jotted-down thoughts. Without Hwie, the letters would not have reached them. Hwie and Pram also became closer as they regularly exchanged ideas, and Hwie readily provided anything that was needed for the creative process of the Blora-born writer.

Memories: Photos show Hwie with Pramoedya Ananta Toer after the writer was released from imprisonment on the island of Buru in 1980. (JP/Ivan Darski) (JP/Ivan Darski)"Pram, at that time, had a different cell. He was utterly exiled, and other prisoners were forbidden to approach him. He was isolated in a hut near a field. We had to make our way secretly if we wanted to meet Pramoedya. If we were caught by the guards, well, just be prepared for this,” Hwi said, raising clenched fists. “But that didn't scare us. We just took it all. The most important thing was for Pram to be able to continue writing and sharing his thoughts.”

Other prisoners were also involved in the writer’s process. For example, when Pram was writing a non-fiction book titled Perawan Remaja Dalam Cengkeraman Militer (teenage virgins in the military’s grip), fellow prisoners helped with the research by visiting and chatting with former jugun ianfu [comfort women] on Pram’s behalf.

"In between work in the forest and fields, friends visited the many jugun ianfu who were stranded on Buru. After that, we delivered our research to Pram. And then the book was published," explained Hwie.

Cement sacks, indigo and outhouses

On Buru, silence and solitude were familiar companions to the prisoners. The 12,656 square kilometer island in Maluku province was only inhabited by a handful of residents, soldiers and political prisoners. There, everything was limited. The prisoners had to hunt rats, crickets and work the fields to fill their stomachs. According to Oei Hiem Hwie, it was not uncommon for the detainees to die of starvation.

"Getting enough to eat was hard. Can you imagine how it was to write? You had [the ideas] in your head, right? We were being watched 24 hours a day. We had to rack our brains to be able to write. We took advantage of everything we had: charcoal, indigo sap, cement sacks, anything so that Pramoedya could keep writing," said Hwie.

On Buru, paper was very scarce. Pramoedya often wrote on dry leaves or on old cement sacks. For ink, they used pigment from nearby indigo plants or charcoal from firewood. To outsmart the security guards, Hwie dug a hole made to look like an outhouse and placed a cement cover on top. In emergencies, the manuscripts were hidden in that hole.

"Soldiers couldn't possibly check. They thought it contained shit. Actually, Pram's handwritten manuscripts were inside."

After Pramoedya finished writing, Hwie borrowed a typewriter from the command secretariat's office to copy the manuscript. Hwie would read the text aloud as one of his close friends, Paimin, a political prisoner from Tegal, typed.

"After that, the manuscripts were distributed to other detainees to be read, commented on and evaluated. In addition, copies of the manuscript were also made in case the original manuscript was confiscated and burned."

Smuggling the text out

A fresh wind of hope blew sweetly into Oei Hiem Hwie's ears at the end of November 1977. At that time, he was watching television at the military command headquarters. There was a news report on the potential release of political prisoners like himself.

"When I heard it, I felt pessimistic. It wasn't the first time such news had come to us. These words were often spoken by the international world, but then it never happened," Hwie said.

But one year later, in November 1978, Hwie was informed that he would be returned to East Java. After hearing what seemed like the happiest news in the past 15 years, he told his best friend. But Pramoedya’s name did not appear on the list of political prisoners to be released.

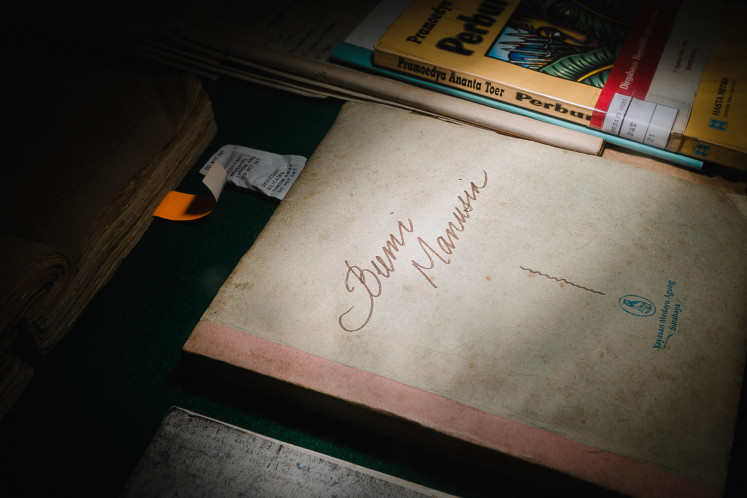

"He said to me, ‘Hwie, I'll just leave this to you.’ And then he handed me a bundle of paper containing handwritten notes, which today is known as Bumi Manusia."

Piece of history: A draft of Bumi Manusia (This Earth of Mankind). (JP/Ivan Darski) (JP/Ivan Darski)Even though he was haunted by fears of being searched and his return was delayed, Hwie did not flinch. He was determined to fulfill his friend’s request.

"I figured it out. I put the manuscript in a besek [bamboo container] mixed with dirty clothes, dishes and food. I also brought the cement casting we usually used to hide the manuscript. It was a political witness – a mute, silent witness to our journey," said Hwie.

Two years later, in 1980, Hwie heard that his comrade had been freed. Pramoedya finally returned to Jakarta, and an overjoyed Hwie left for the city. When they met at Pramoedya's house, his best friend refused to take back the notes he had given to Hwie when they were in exile.

“No need. You just keep this. Please give me the copied version. The original one is a keepsake from me. Keep it, because it's dangerous here as it can be seized by the army," said Pramoedya, according to Hwie.

The manuscript now resides in a special glass case in the Medayu Agung library, which belongs to Hwie. It is exhibited alongside other manuscripts written by Pramoedya on Buru. In addition to Bumi Manusia, Hwie brought a manuscript entitled Enskiplopedi Citrawi Indonesia [encyclopedia of Indonesian images]. The manuscript was never published as Pramoedya passed away before it had reached the publisher.

Collectors have offered Hwie billions of rupiah for the collection.

"This is a witness to history,” he said. “Money could never buy our hardships or our friendship, we who were political prisoners, victims of state atrocities.”