Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsAdolfs: Generic beauty in the Dutch East Indies

To begin with, there can be no doubt that this sumptuous work is a must, in spite of its steep price, for the library of anyone interested in the Indonesian art scene or Dutch colonial lifestyle from 1920 to 1940

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

To begin with, there can be no doubt that this sumptuous work is a must, in spite of its steep price, for the library of anyone interested in the Indonesian art scene or Dutch colonial lifestyle from 1920 to 1940.

That said, while the ostensible subject of this immense tome, the self-taught artist Gerard Pieter Adolfs, produced some competent and even good work (my favorites are his graphic material) during his career, he will always remain a minor artist from a provincial neo-Impressionist school of painting known as the “Beautiful Indies Style” that is ultimately, eminently forgettable.

And so, it should come as no surprise that the book is important not because of the art itself (even luxurious foldouts cannot elevate the mundane), but rather the designer’s creative combination of diverse illustrative material (photos, memorabilia, drawings, sketches and desiderata) that have resulted in a fascinating historical document.

The text, written by Adolfs’ granddaughter and her husband, is informative and revealing in spite of some predictable forays into sentimentality. The combination of family stories and photos give a rare and intimate glimpse into colonial highlife in the 1920s and 30s.

Born in Surabaya to a Dutch father and Javanese mother, Adolfs was an intriguing and sometimes notorious figure with a well-earned reputation as a playboy. Diminutive by stature and dapper by character, the young man with elephantine ears was ambitious, self-assured and always dressed to kill. He also had a keen sense of publicity and would become something of a native hero in the city of his birth; greeted at the harbor by adoring reporters when he disembarked from his European tour, and proclaimed “The Wizard of Light”.

In the 1920s, Adolfs would hand-paint the provocative flapper gowns of his pretty young wife, Eveline, with gold Art Deco motifs. The toast of the town, these collected numerous prizes as Surabaya’s best Tango dancers (yes, the Tango is not new to Indonesia) wore them in Surabaya’s steamy clubs. The image gives a better idea of why many of the expatriate luminaries of Bali’s pre-World War II “Golden Age” (like the Mexican Miguel Covarrubias and his exotic dancer wife, Rose) took regular trips to Surabaya to escape Bali’s bucolic splendor!

While Adolfs may not have been a great artist, he had a quick mind and sharp tongue that he was not afraid to unleash on his critics. In the 1930s, Adolfs would send a series of testy diatribes to editors of nearly every colonial publication to denounce the “decadent” influence of European Modern Art and the need to defend Indonesia’s “native” born painters (he considered himself 100 percent Indonesian).

These epistles present one side of the clash of values and aesthetics that would give birth to Persagi, Indonesia’s first modern art movement – whose members denounced the pretty pictures of the colonial elite that Adolfs so vigorously defended.

His opinions on modern art were so reactionary that he even evoked the scorn of fellow artist and friend Dolf Breetfeld who wrote a scathing rebuttal: “the task of extracting precise meaning and thought – supposing there is any to be found – from Mr. Adolfs’ labyrinthine sentences is, as usual, a thankless one.” His warning served no purpose as Adolfs’ already large ego, propped-up by steady profits reaped from exhibitions catering to the conservative tastes of the colonial elite, allowed no self-doubt.

His public, like him, had a deep suspicion and distaste for Europe’s modern art movements – including Expressionism, Cubism and (as Adolfs disdainfully pronounced) other ‘isms’ being pushed by a new generation of art critics headed by Jeanne deLoos-Haaxman, the new director of the association of the colony’s exclusive Art Circles (Kunstkringen).

War was declared between Adolfs and deLoos in 1936 when she declared five of the 30 works he submitted for an exhibition were “unsuitable”. Adolfs leaned on powerful friends and had the decision reversed. Oblivious to her opinions, he celebrated by buying a new MG sports car.

As most monster art productions destined for the Indonesian market, this book would have benefited from better editing, and 100 fewer pages. One wonders how long it will take before somebody realizes that a glut of similar looking images dulls rather than excites the imagination.

Ironically it also seems to empirically prove the accusations of Adolfs’ critics; that his art is generic fluff. Other shortcomings include too many stock photos from his foreign journeys (we all know what Paris and Rome look like) and an indulgent chapter on the art of Adolfs’ daughter that from the point of view of art history does not even qualify as a footnote to a footnote.

Sadly, an essay on Adolfs’ place in the Beautiful Indies School that could have been the high point of the book is used instead as an excuse to cram in images of better-known artists presumably to increase the book’s marketability. Another low point is the pseudo-poetic, neo-hippie terminology (vibrant, sparkling, luminist) used to describe the artist’s stylistic phases.

The Second World War and Indonesian Independence brought tragedy and hardship especially to the Indo (Dutch-Indonesian) community, who were officially Dutch, but in reality Indonesian. Adolfs’ case was particularly tragic because he was caught in Amsterdam during the German invasion of 1940, after impetuously deciding to leave his jealous wife, beloved daughter and Surabaya. Destitute, he would live a subsistence existence while writing forlorn letters to his wife – ruing his rash decision and re-affirming his unwavering love – unaware that she had passed away shortly after the Japanese invasion of Surabaya.

Fate would prevent any return to the land of his birth before Adolfs’ death in 1968. Like other colonial artist refugees, he continued to paint anachronistic Indonesian scenes from his Amsterdam flat. Adolfs’ prospects shrank as the market for colonial scenes shrank. The new generation of Dutch had no fondness for tempoe doeloe and even looked upon their nation’s colonial legacy and ex-colonialists with mixed feelings, if not shame. As a result, Adolfs was largely forced to sell his exotic tropical scenes and topless women elsewhere in Europe where no such sentiments lingered. Sadly he would not live to see the resurgence of interest in Indonesian colonial paintings that first took off in the 1980s when more of his paintings and those of other members of the Beautiful Indies School started appearing in auction catalogues.

In spite of a momentary spike, few of these ever achieved the grand prices fetched by Spies, Le Mayeur, Hofker or Bonnet.

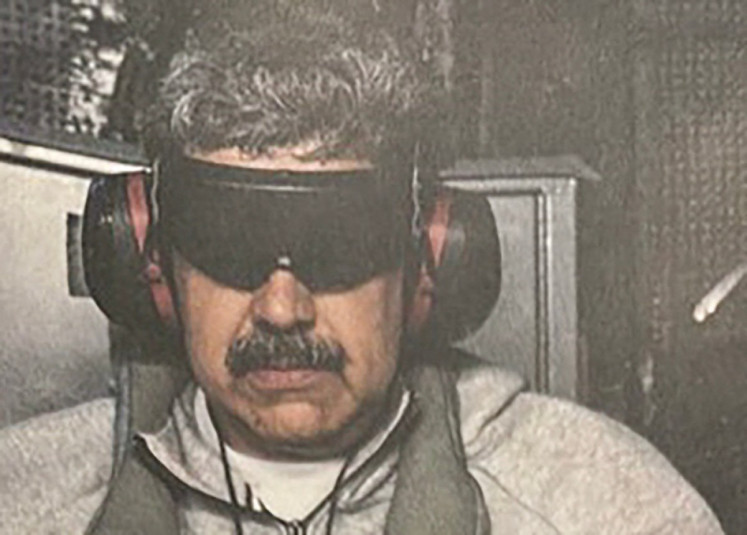

One of Adolfs’ European works, a portrait of a Balinese Legong dancer (1944), is featured on the cover. Its selection seems to have been driven by emotional attachment of the owners and sponsors rather than any great aesthetic value, since (at least in the opinion of this critic) it is rather weak if not unattractive, with a clumsy positioning of the hands unlike any Balinese mudra I know. From a Freudian point of view, however, the resemblance of the flat-breasted dancer’s rather masculine visage to a morose photo portrait of the artist’s wife (taken in the 1920s when they temporarily separated after quarreling over his philandering) is suggestive to say the least.

On a related note, it appears that the authors, their advisors and their publisher were unaware of (or chose to ignore) Adolfs’ student and most obvious successor – Koempoel Sujatno (circa 1912 -1987). Introduced to Adolfs by his headmaster, Koempoel studied under Adolfs’ tutelage from 1928-1932. The similarity between both men’s work leaves little doubt of Adolf’s enduring influence.

Already considered an accomplished painter in the 1930s, it is interesting to note that a Koempoel ‘s sold for only 5 guilders in contrast to the 50 demanded by the elitist Adolfs – a direct factor of their respective positions in society. While the injustice first chaffed Koempoel, the egalitarian ideals of the revolutionary struggle caused him to aspire to bring the joy of art to the masses, even if it meant he would remain a poor man.

Over the next decades Koempoel would paint thousands of city and landscapes and sell them for a pittance to achieve his goal as one of the more talented of countless (usually anonymous) painters who emulated the Beautiful Indies School even after Indonesian independence.

While many of his paintings are generic and decidedly commercial, Koempoel also produced a significant body of work that has since caught the attention of art critics and collectors.

Ironically a large book on his work, Koempoel Sujatno; the Maestro, was published with the support of the city of Surabaya in 2003, five years before that of Adolfs. If imitation is indeed the highest form of praise, Koempoel proved, at the very least, the continuing appeal

of pretty, albeit romantic images of a magic, bygone era that was probably largely imaginary in the first place.

While Adolfs may have protested at its implication, the fact that Koempoel’s work now fetches about the same prices as Adolfs’ on the Indonesian art market speaks for itself.

Gerard Pieter Adolfs

• Painter of Java and Bali 1898-1968

• Eveline Borntraeger-Stoll and Gianni Orsini

• 420 pages

• Full color, with more than 800 paintings, drawings, etchings, photographs

• Pictures Publishers, the Netherlands, 2008

• Available at some Periplus Stores