Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsBurial of Christian test of tolerance in Yogyakarta village

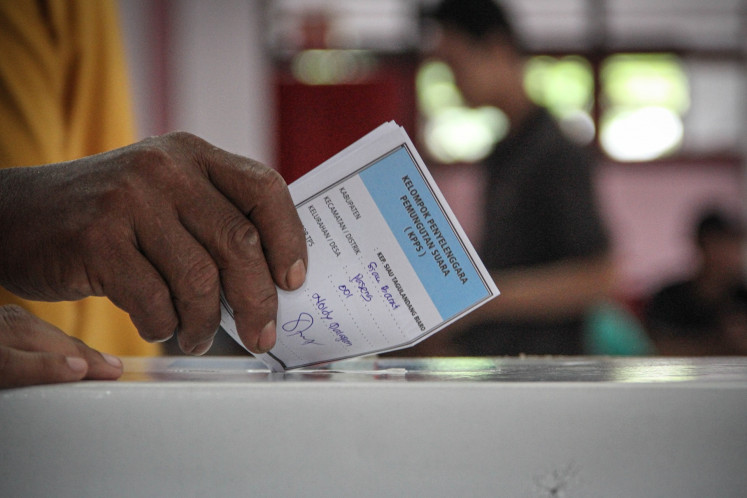

Grave concern: A headstone at the grave of Albertus Slamet Sugihardi, 63, at the Jambon cemetery in Purbayan village, Kotagede, Yogyakarta, is no longer shaped like a cross as residents cut part of it off

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

G

rave concern: A headstone at the grave of Albertus Slamet Sugihardi, 63, at the Jambon cemetery in Purbayan village, Kotagede, Yogyakarta, is no longer shaped like a cross as residents cut part of it off.(JP/Bambang Muryanto)

Albertus Slamet Sugihardi, a Catholic, had been a resident of Purbayan village in Kotagede, Yogyakarta, for a long time.

So when he suffered a heart attack and died at the age of 63 on Monday, his wife, Maria Sutris Winarni, 63, wanted her deceased husband to be buried at a cemetery not far from their house.

Little did she know that her simple wish would end up adding salt to her wounds and lead to some soul-searching within the country, which is now grappling with simmering intolerance.

The predominantly Muslim villagers in Purbayan allowed the grieving family to bury Slamet at the local cemetery, but with certain conditions attached: There should be no cross on his grave and the family is not allowed to conduct prayers near his grave.

“This is community consensus. He could be buried here, but there should be no Christian symbol,” Bejo Mulyono, a local figure, told reporters on Tuesday.

On Slamet’s grave, the top of a cross-shaped gravestone was cut off by residents. It now looks like the letter “T”, while the cut-off portion, which bears the wish “RIP”, has been placed beside it.

“[The people] who cut off the top of the cross live near the cemetery,” Soleh Rahmad Hidayat, the community head, said.

Bejo said the majority of Purbayan’s residents were Muslims, and that those buried at the local cemetery were Muslims. Slamet, he said, was allowed to be buried at the cemetery “because it was an emergency”.

Also, Slamet could only be buried on the periphery of the cemetery, he added.

He said all the requirements were made because in the future the Jambon cemetery would exclusively for Muslims.

“Our village is tolerant, except for religious rituals,” Bejo said.

He argued that non-Muslims were prohibited from holding prayers to avoid conflict with residents who objected to such religious activities.

He claimed that Slamet’s family had accepted the rule, showing what he said was a statement from Slamet’s wife that she accepted the rules and would not make an issue of the matter.

Yogyakarta Interfaith Brotherhood Forum secretary-general Timotius Aprianto deplored the incident, saying that religious pluralism was only recognized formally but not substantially embraced by society.

“We will hold a meeting with the Kotagede community,” he said.

While the incident sparked outrage on social media, religious leaders appear to have been more composed in their responses.

Indonesian Communion of Churches (PGI) executive and priest Jimmy Steven Sundalangi regretted that the cross had to be cut so that Slamet could be buried in the cemetery.

The priest, however, acknowledged that there was an understanding between religious communities about cemeteries for Muslims and non-Muslims.

“We just need to respect the [separation]. We do not need to force it,” he said.

Christians, he said, were accepting of the cutting of the cross, as they did not worship symbols.

He, however, deplored the fact that Slamet’s family was not allowed to conduct prayers near the cemetery.

“If prayers are prohibited, I think that is out of line. This is the first time I’ve heard of something like this,” he said.

Muhammadiyah secretary-general Abdul Mu’ti downplayed the significance of the incident, though he said the cutting of the cross was “unnecessary”,

“This is not a big deal. In several places, Muslims and non-Muslims are buried on different sides of the cemetery. I think the community leaders have the authority,” he said. He explained that some Muslims believed that Muslims and non-Muslims should have separate cemeteries.

Nahdlatul Ulama legal division head Robikin Emhas concurred with Mu’ti, saying that Muslim cemeteries should be separate.

“In this case, we cannot say the community is intolerant because Islam actually regulates this matter, but cutting off the top of the cross will not solve the problem,” he said.

He said the community and local administration should provide a specific place for non-Muslims to be buried so that similar cases did not arise again.

Institute for Policy Research and Advocacy researcher Wahyudi Djafar said the case appeared to legitimize the findings of several recent surveys regarding the rise of intolerance in Indonesia. In Yogyakarta in particular, there has been many cases of friction between religions that have not yet been fully resolved.(ggq)