Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsRI democracy at lowest point: Scholars

Is Indonesia’s much-lauded democracy backsliding? A growing number of observers agree that Indonesia is not a full democracy, but instead has evolved into some other, more illiberal form of democratic government

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

I

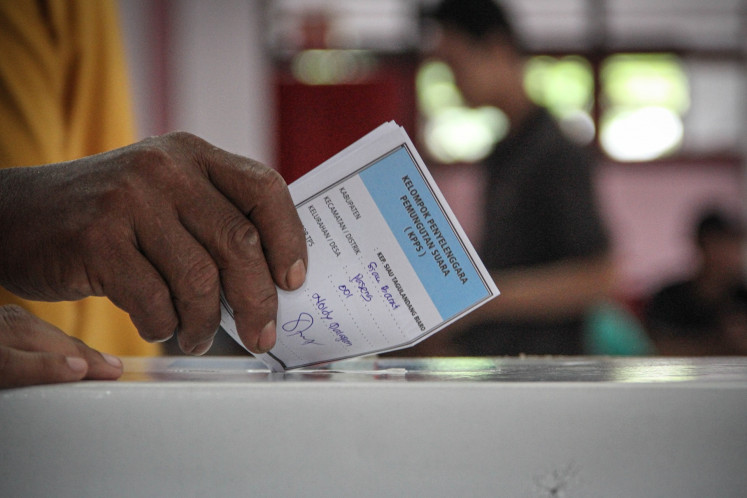

s Indonesia’s much-lauded democracy backsliding? A growing number of observers agree that Indonesia is not a full democracy, but instead has evolved into some other, more illiberal form of democratic government.

According to Australian National University (ANU) political scientists Edward Aspinall and Marcus Mietzner, Indonesia meets the requirements for an “electoral democracy”, which constitutes “the minimal level in the hierarchy of democratic polities”. But other important features of a full democracy, like protections for minorities, freedom of speech and freedom of organization have all eroded over the course of the Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono and Joko “Jokowi” Widodo presidencies.

Recent events confirm the worrying state of Indonesian democracy. A wave of online and offline protests led by activists, academics and members of the public as well as critical media outlets failed to stop the Jokowi administration and the House of Representatives from deliberating and passing a law amendment that weakens the Corruption Eradication Commission (KPK), a once-independent body that has become the nation’s leading icon in the fight against graft.

Prior to the law amendment, the lame duck lawmakers agreed to revise the Legislative Institutions ( MD3 ) Law to basically allow political parties to get a seat in the People’s Consultative Assembly (MPR) and enable power-sharing among themselves.

But such “collusive” maneuvers are only the most recent examples that serve as symptoms of the country’s “slow but notable democratic decline”, as described by Aspinall and Mietzner during the ANU Indonesia Update conference in Canberra on Sept. 6 and 7.

This year’s Indonesia Update conference bore the theme “From stagnation to regression? Indonesian democracy after twenty years.”

“Political illiberalism, weakening party foundations and escalating sectarian polarization have significantly undermined Indonesia’s democratic quality. This trend, which began in the early 2010s, extended into the 2019 elections and was accelerated by them,” they argued.

Aspinall and Mietzner cited the V-Dem Index of Deliberative Democracy, which suggested that Indonesia was at its democratic highpoint in 2006, and declined with fluctuations after that year. Meanwhile, Freedom House and the Economist’s Democracy Index also confirmed the trend, suggesting that Indonesian democracy is “above the minimum threshold of an electoral democracy, but well below the democratic quality it had in the mid to late 2000s”.

Speakers at the conference documented the Jokowi administration’s “illiberal” policies, justifying repressive measures to restrict Prabowo Subianto’s populist-Islamist campaign as a means to “protect Indonesia’s pluralist constitution”. One example was the Jokowi administration’s decision to ban Hizbut Tahrir Indonesia (HTI), a nonviolent Islamic organization seeking to establish a global Islamic caliphate, in 2017. But there were others too. Ken Setiawan of Melbourne University, another conference speaker, cited a range of cases that show how freedom of expression on and offline had eroded significantly in recent years.

Other researchers, including Eve Warburton of the National University of Singapore, explored deepening political polarization since 2014 along the Islamist-pluralist cleavage, and argued this was one of the key factors eroding democratic quality in the country. She compared Indonesia to deeply polarized countries like America and Turkey, and found that many worrying signs of polarization can now be found in Indonesia. For example, in election campaigns, she noted the delegitimizing of political opponents on both sides, and an increasingly toxic “us versus them” discourse.

This has led to animus between people on different sides at the community level. Using recent survey data, Warburton found 39 percent of Indonesians want to live in areas where people vote the same way. The number is slightly higher for Prabowo supporters (40 percent) and Jokowi supporters (44 percent). In international terms, these numbers are relatively high, she argued.

The findings reflect the socioreligious division that characterized the election outcome. An exit poll conducted by Jakarta-based pollster Indikator Politik Indonesia, showed that in 2019 Jokowi won a staggering 97 percent of non-Muslim voters, a 10-percent increase from the previous election, and 56 percent of voters affiliated with Nahdlatul Ulama (NU), the country’s largest Muslim organization, whose central figure Ma’ruf Amin ran as vice president alongside Jokowi in 2019.

NU has been an icon for a more moderate brand of Islam, in contrast to the more Islamist ideology demonstrated by Prabowo supporters. Though, as Nava Nuraniyah of the Institute for Policy Analysis and Conflict pointed out in her conference presentation, NU has become increasingly militant and has also contributed to a more polarized political landscape.

The decline in democratic qualities was also reflected in the ways voters responded to the election outcome and their perceptions of the way democracy works. Assessing attitudes among electoral losers in the 2019 elections, Burhanuddin Muhtadi of the Syarif Hidayatullah Islamic State University found that, “Losers in 2019 are more likely to perceive the election as less free and fair. The losers were convinced that their freedom of speech and freedom of association are being undermined.”

Such presumptions were not baseless. Among the most recent cases were online intimidation against academics and antigraft activists, who have been criticizing both executive and legislative’s moves that might jeopardize civil liberties through, among other means, the controversial revision of the Criminal Code. If passed, the new Code may further marginalize vulnerable groups, such as women and the lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) community, and restrict public criticism of the president.

Not all arguments were grim, however.

Risa J. Toha of the Yale-National University of Singapore College, reminded the audience that Indonesia still had an impressive record when it came to conducting elections, with very few cases of election-related violence taking place around the country since the reform movement.

At the same time, her research showed violence was higher in restive provinces such as Papua and Aceh and in areas with a long history of ethnocommunal conflicts such as Kalimantan and Maluku. Speakers from PUSAD Paramadina, Dyah Ayu Kartika and Irsyad Rafsadie agreed, with their presentation on West Kalimantan’s election highlighting the ongoing risks of electoral violence in post-conflict communities.

Dan Slater of the University of Michigan saw the glass as half full as well. He argued that Indonesia should be lauded for having avoided three of the four major pitfalls that a new democracy often confronts: state failure, military takeover and electoral authoritarianism. He said it was vital to appreciate that these threats “have all been successfully evaded and I expect those critical evasions to continue”.