Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsHow will ASEAN leaders approach regional COVID-19 response at 36th summit?

As the leaders of Southeast Asian nations prepare for the virtual 36th ASEAN Summit on Friday, we ask three key questions on their varying responses to the regional COVID-19 pandemic.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

W

ith its member states at different stages in their COVID-19 responses, a coordinated regional response will likely be top-of-mind as the nations' leaders prepare to convene virtually for the 36th ASEAN Summit on Friday.

Indonesia last week surpassed Singapore as the ASEAN nation with the highest cumulative total of confirmed cases, as its daily tally continues to hover around 1,000 new cases. Meanwhile, other ASEAN states like Vietnam, Brunei and Laos have all reported zero cases over the past few weeks.

Grouping nations with diverse governing systems and cultures, ASEAN has been strongly criticized for being too slow in responding to the pandemic, even though some sectors began discussing regional cooperation very early on.

How has ASEAN and individual states responded to COVID-19?

ASEAN began discussing collaborative action immediately after the World Health Organization (WHO) declared the COVID-19 outbreak a “public health emergency of international concern” on Jan. 30.

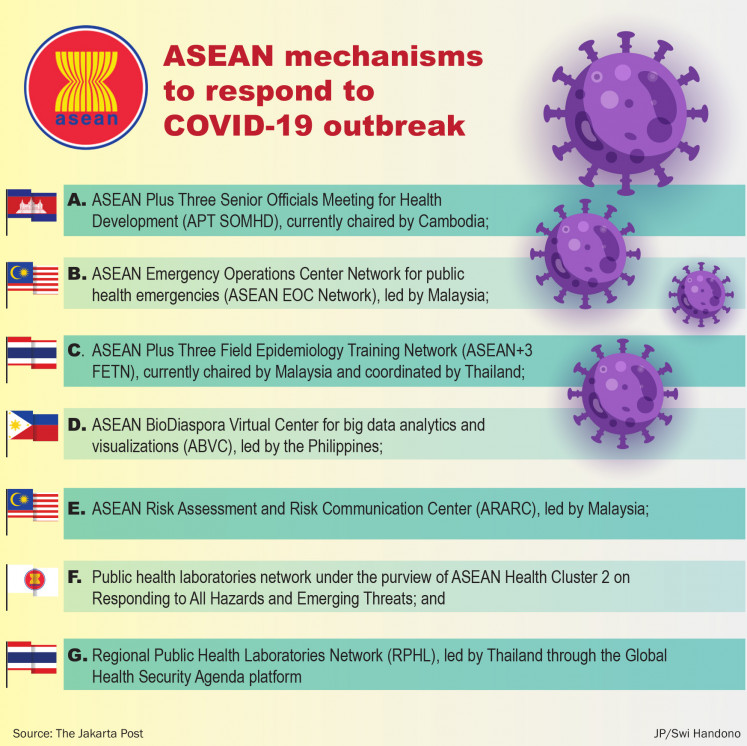

It also activated various existing regional mechanisms, such as the Regional Public Health Laboratories Network (PHLN) and the ASEAN Emergency Operations Center Network (EOC Network). These public health emergency mechanisms were installed as a result of past lessons learned, including the 2003 SARS outbreak that plagued the region.

Lessons learned: ASEAN has activated several public health emergency mechanisms that were established in response to past outbreaks, like SARS. (JP/File)ASEAN health ministers convened a meeting in late January, followed by a flurry of coordination meetings in other sectors including foreign affairs, defense, tourism, labor and agriculture. The meetings discussed collective outcomes and collaboration initiatives that were pooled and then presented at the ASEAN Summit on April 14.

Observers have noted the common resolve among ASEAN states to avoid insular or protectionist policies in their respective approach to COVID-19 mitigation and management, and lauded their commitment to keep markets open while continuing to support a rules-based international trading system.

Bilaterally, ASEAN states have also helped each other by providing medical equipment, supplies and other goods.

Individually, however, all 10 member states, have been at different stages in their COVID-19 responses, with some countries succeeding at containing the virus while others still grappling with high rates of infection.

*data from June 23, 2020

As the region’s most populous country, Indonesia has the highest tally of deaths linked to the disease with 2,573 total deaths as of June 24. This is more than twice that of the Philippines, which has the second highest death toll in ASEAN with 1,204 deaths.

Meanwhile, other ASEAN states have managed to maintain relatively low death tolls: Singapore has recorded 26 deaths to date and Vietnam has succeeded in containing its outbreak with zero deaths.

Why does ASEAN have such a wide statistical gap?

Indonesia has the largest territory and population in the region, with 267.7 million people across 34 provinces. However, its national healthcare system is woefully underprepared to manage the highly contagious virus, which has contributed to its high COVID-19 death toll.

Before additional ventilators and isolation rooms were provided to the Kemayoran Athletes Village COVID-19 emergency hospital in Central Jakarta, only 8,158 ventilators and 105 isolation rooms equipped with ventilators were available nationwide, according to Health Ministry data.

Read also: Grim result from COVID-19 modeling

The ministry data also shows that Indonesia has around 143,000 nurses and 22,000 doctors, with only 807 pulmonologists capable of treating the acute respiratory syndrome caused by the coronavirus. In comparison, Vietnam had readied 125,000 nurses and 90,000 doctors to serve its 95.54 million population, according to local news.

It all comes down to the response and preparedness of each individual nation.

Virtual safety: President Joko "Jokowi" Widodo (center), accompanied by Foreign Minister Retno Marsudi (rear left) and Health Minister Terawan Agus Putranto, attend the virtual ASEAN Plus Three Summit on April 14 from Bogor Palace. Indonesia has recorded the highest cumulative total of COVID-19 cases among ASEAN states. (Antara/Biro Pers - Lukas)Indonesia was among the last few countries in the region to confirm a local outbreak, reporting its first cases in early March. However, the government was reluctant to impose a nationwide lockdown and only took action nearly two weeks later with the introduction of the large-scale social restrictions (PSBB), which required regions to apply for prior ministerial approval.

Malaysia also dithered in its initial response, which was further complicated by an abrupt change in government. But then it immediately announced the movement control order (MCO) following a massive spike in cases in mid-March that originated from a tabligh mass religious gathering.

Read also: COVID-19 cases surge in ASEAN states

The Philippines has among the highest daily increase in new cases in the region. Observers say that Manila also veered from dismissing the threat of COVID-19 to imposing heavy-handed policies.

Singapore embedded social distancing measures in the "circuit breaker" program it implemented in early April, which was highly praised as effective until the virus began spreading among its migrant worker population. Fortunately, its world-class healthcare system kept the virus contained.

Vietnam used targeted lockdowns in select geographical areas, with local authorities managing strict measures on active cases. It also imposed its COVID-19 measures early, starting with travel restrictions in January. These tactics helped prevent wider spread of the disease among its population.

The remaining ASEAN states have reported low numbers of cases and deaths, such as in Myanmar, but observers have noted that this could be attributed to a lack of testing.

What can we expect from the summit?

ASEAN leaders are expected to issue a statement on a cohesive and responsive ASEAN on the issue of the regional COVID-19 response, according to the Indonesian Foreign Ministry's ASEAN affairs director general, Jose Tavares.

Among the key issues for potential discussion are measures to control the virus' spread, mitigation of social and economic impacts like unemployment and poverty, and economic recovery plans, said Dewi Fortuna Anwar, a research professor at the Indonesian Institute of Sciences Center for Political Studies (P2P-LIPI).

“I think they will focus on how to increase the resilience of each country and regional cooperation, both within ASEAN and with dialogue partners to assist ASEAN capabilities in these three issues,” said Dewi.

However, the 10 members' differing stages of response may complicate the grouping's efforts to agree on a collective action, said Ibrahim Almuttaqi, head of the ASEAN studies program at The Habibie Center.

“We may see ASEAN hamstrung by its old problem of only being as strong as its weakest members, and any regional response may have to be a watered-down, ‘low-hanging fruit’ version that takes into account the limitations of countries that are still struggling with the pandemic,” he said.

Dewi further cautioned that the region should not lose sight of the current geopolitical situation, especially the rivalry between the United States and China that has spilled over into other issues, such as the virus' origin and the WHO's role.

“Amid the COVID-19 pandemic, ASEAN countries have tried not to play the blame game with China, whose ‘COVID-19 diplomacy’ has turned it from a country unable to control the spread of the virus to a country that sends medical supplies and assistance,” she said.

Indonesian Foreign Minister Retno Marsudi told reporters on June 25 that the summit provided an opportunity for the leaders to “further consolidate and coordinate efforts to mitigate COVID-19 and its impact”.

She said Indonesia would raise two important points: that ASEAN must work harder on staying relevant in the face of major power rivalries, and that it must increase its collective capacity to mitigate the pandemic.

At the Informal Meeting of ASEAN Foreign Ministers a day prior, member states also underlined the importance of keeping track of shared concerns beyond the pandemic.

Retno highlighted the issues in the South China Sea, calling on all ASEAN states to contribute toward building stability and peace in the disputed waters.

“Indonesia believes it is time to resume the COC [Code of Conduct] negotiations, which was suspended because of the pandemic. We believe that the COC will contribute to an environment conducive [to peace and stability],” she said.

The minister also stressed the importance of preventive measures in handling the refugee crisis in Myanmar's Rakhine state.