Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsTerawan in hot water again, this time over radiology services

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

H

ealth Minister Terawan Agus Putranto, a radiologist who heads the Indonesian Radiology Specialists Association (PDSRI), has come under fire yet again after issuing a regulation that many doctors say prioritizes radiologists and could have negative impacts on prompt treatment of patients.

Sixty-four of 76 specialist doctor organizations and medical specialist academy councils have signed a letter urging Terawan to revoke Ministerial Regulation No. 24/2020 on clinical radiology services.

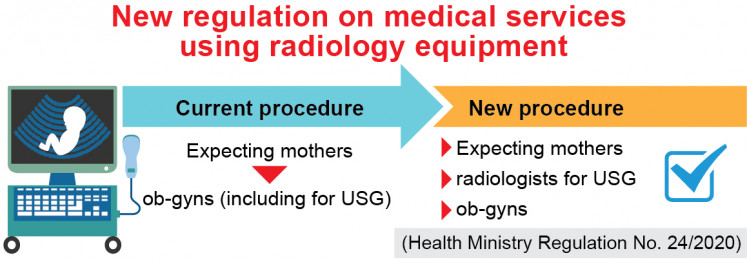

The regulation requires health facilities providing services involving radiation instruments -- from community health centers to clinics and hospitals -- to have radiologists.

Primary service providers who offer mobile or dental X-ray services and ultrasonography (USG) but do not yet have any radiologists must employ either general practitioners or other specialists with radiology-related skills as proven by certificates from the Radiology Collegium, a radiology specialization education board. They must also be supervised by radiologists.

Those providing more advanced services, from CT-scans and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to digital subtraction angiography (DSA) must have at least two to four radiologists, depending on the levels of their services.

In the letter, doctors said Terawan had “prioritized fellow radiologists in medical services that make use of radiology instruments [...] when other doctors have met the standards for competency and qualifications both in terms of knowledge [and] skills” in line with the 2004 Law on medical practices and with Indonesian Medical Council (KKI) regulations.

The regulation, they added, would put doctors in uncomfortable situations and erode teamwork at a time when it was needed the most amid the country's ongoing battle against the COVID-19 outbreak.

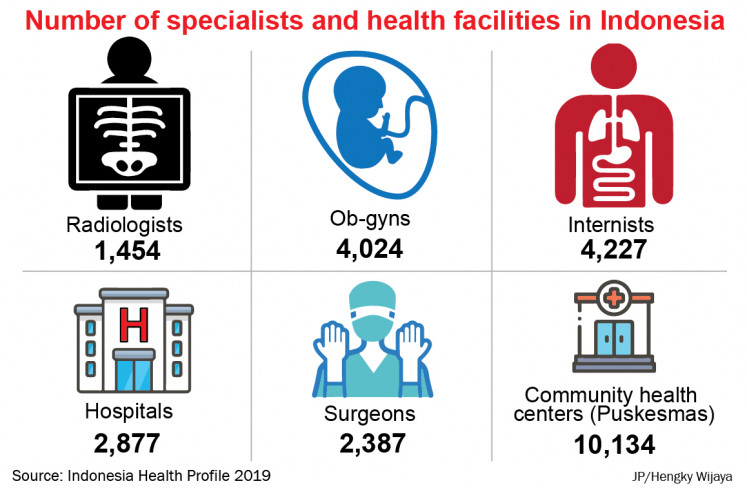

The doctors said they were worried most about how the regulation would disrupt healthcare services, as a deficit of radiologists was to be expected, even with the regulation giving a two-year grace period for healthcare facilities to adjust.

Read also: Stretched thin, Indonesia deploys medical interns to COVID-19 front lines

Only 1,578 of some 41,000 specialist doctors in the country are radiologists, according to the chair of IDI's Academy of Medicine of Indonesia (MKKI), David S. Perdanakusuma. Indonesia has about 3,000 hospitals and 10,000 community health centers.

David said the regulation would mean that services involving radiology instruments might only be provided by a much smaller number of radiologists, while in fact, all this time, they had been provided by 25,000 specialists from 15 different fields, and by many general practitioners. He expressed concern that this would jeopardize the prompt delivery and quality of patient treatment.

For instance, he said, expecting mothers would have to first visit radiologists for USG instead of simply visiting ob-gyns -- when USG had become like a stethoscope to doctors, meaning it was no longer a special procedure.

"Patients' pathway [to treatment] will be longer, the expenses will be higher and it will also be time-consuming. If there's an urgency, such as fetal distress, ob-gyns would notice it sooner to decide on surgery,” David told The Jakarta Post. “It could affect patients' safety if decisions are tardy.”

The uneven distribution of specialists across the country is another reason why many doctors deem the regulation problematic. The chair of the Indonesian Medical Association’s Professional Service Development Council (MPPK), ob-gyn Poedjo Hartono, said general practitioners in rural areas were expected to run basic USG on pregnant women for the early detection of abnormality, allowing them to refer patients to bigger hospitals as early as possible if necessary.

Poedjo said he feared that, by limiting this procedure, the country's already high maternal and child death rates would only rise further. And this concern was not limited to childbirth but applied also to other life-saving procedures requiring early and well-performed diagnosis as well as prompt action, such as coronary stent placement, he said.

"There's a shared competency [between specialists]; we're not eliminating each other. There's been no problem with radiologists while providing services [...]. So what's the use of this [regulation]? It'll only lead to disorder," Poedjo said.

David said that with the regulation, the MKKI would also have to make changes in the medical education of the 15 specialty fields as well as for radiologists, affecting at least 8,953 residents. Radiology, for instance, had thus far been rather focusing on diagnostics, but with this regulation, it would have to also cover therapy.

He said the deliberation on the regulation had actually begun in May, but doctors refused to continue with it, as they were preoccupied with the COVID-19 outbreak.

Read also: COVID-19 deaths 'redefinition' prompts pushback

David criticized Terawan for issuing the regulation even though important stakeholders had not been involved in its deliberation. He questioned the urgency of such a regulation that would not even help the country fight the pandemic. David alleged there were conflicts of interest in the deliberation.

The Health Ministry had invited doctors to inform them on the regulation, which the doctors associations had refused, insisting instead that the regulation be revoked, David said.

"Doctors' competencies are regulated by medical academy councils and the KKI, not by ministerial regulations," he added.

The problem, doctors noted, was that the recently inaugurated KKI members had been opposed by various doctors associations, who said that none of the chosen names had been among candidates proposed by the groups.

Read also: Six months on, health experts covet greater voice in pandemic response

Radiologist and former IDI chairman Prijo Sidipratomo said overlapping competencies were normal in the medical world, and if there was to be a regulation on that, especially concerning workers' and patients' safety around imaging instruments used in radiology, it should have been the authority of the KKI and the Nuclear Energy Regulatory Agency (Bapeten), not the Health Ministry.

Prijo said that, if the ministry was to get to the root of the problem, it should change the fee-for-service system into a salaried system for doctors, since that would allow them to work in teams involving various specialists to assess patients.

The ministry’s acting health services director general, Abdul Kadir, did not immediately respond to a request for comment.