Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsShort-circuited by red tape, companies struggle to electrify remote areas in Indonesia

The government prioritizes PLN, the country’s legally monopolistic but cash-strapped power distributor, while crowding out private enterprises.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

P

rivate companies across the country are struggling against government regulations as they attempt to provide isolated regions in the country with clean energy, partly due to strict government policies that often prioritize state-owned electricity firm PLN, despite the latter’s limited funds.

The Jakarta Post reached out to three private companies with projects in remote areas of Sumatra, Kalimantan and Papua, all of which had run-ins with government policy. Only one company, in Kalimantan, successfully completed its project, but at a cost.

In Sumatra, solar startup PT Surya Utama Nuansa (SUN) and a region-owned enterprise (BUMD), PT Bungo Dani Mandiri Utama, planned to build a 7.35-megawatt peak (MWp) solar mini-grid to power the riverside villages in Tanjung Jabung Barat, the second-most impoverished regency in Jambi, according to Statistics Indonesia (BPS).

The grid was slated to provide 24-hour power for 8,000 families starting June 2020, assuming all regulators greenlighted the project by 2019.

The companies had secured approval from various regional bodies, including the local energy agency, but then, on Nov. 7, in a fateful letter seen by the Post, the Energy and Mineral Resources Ministry in Jakarta rejected their application for an area electrification permit.

“And that’s where we’ve been held up,” said SUN project manager Verry Kristianto Soeswanto on Oct. 25. “This decision prevents us from further helping the community.”

The ministry wrote that PLN would connect all 19 villages by June this year but that only happened on Nov. 12, and even then the electricity has not yet been turned on.

SUN’s case reflects the government’s approach to electrifying remote areas that, many experts say, risks undermining the country’s ability to empower millions of off-grid, low-income, Indonesian homes – the proverbial “last mile”.

The approach prioritizes PLN, the country’s legally monopolistic but cash-strapped power distributor, while crowding out private enterprises, and even BUMD.

The government’s PLN-first policy is based on the 2009 Electrification Law that grants PLN its monopoly – with exceptions by request – but also obliges the company to electrify the archipelago’s unreachable corners.

“By default, when electrifying villages, it is always PLN even though PLN will not always have the financial capacity to electrify villages or consider it a priority,” said energy analyst Fabby Tumiwa of the Institute for Essential Services Reform (IESR).

PLN recently posted a Rp 12.2 trillion (US$863.1 million) loss in the January-September period, which compares with a profit of Rp 10.8 trillion achieved over the same period last year.

The COVID-19 pandemic has also weighed heavily on the company’s finances, which were already cash-strapped before the global crisis emerged, as the government had instructed the electricity distribution monopolist to lower electricity tariffs, offer discounts to customers and waive subscription fees amid a decline in people’s purchasing power as a result of the health crisis.

“Meanwhile, there is a private company and a BUMD that is able to provide reliable and competitively priced electricity sooner but which are blocked by electrification area regulations,” Fabby said.

SUN and Bungo Dani planned to sell electricity at Rp 3,500 and Rp 4,000 per kilowatt hour (KwH), much cheaper than the Rp 6,000 per KwH that most villagers were paying for diesel-generated electricity.

The villages’ location across a 200-meter-wide river has so far made it difficult for PLN to connect them with the grid in the regency capital of Kuala Tungkal, a low-rise, aging town built beside a river estuary that opens to the Java Sea.

Village head Sutiman of Sungai Kayu Aro village added that the diesel generators only ran between five and six hours each day, starting at 6 p.m. The electricity was just enough to power four lightbulbs per house.

In 2015, Sungai Kayu Aro village, or at least 40 percent of its 330 families, had their first taste of 24-hour electricity when the energy ministry installed a 50 kWp solar mini grid and trained two technicians.

Each home added a TV and charging sockets for smartphones. Public street lights were installed and the village administrative office could run computers, electric fans and a speaker system.

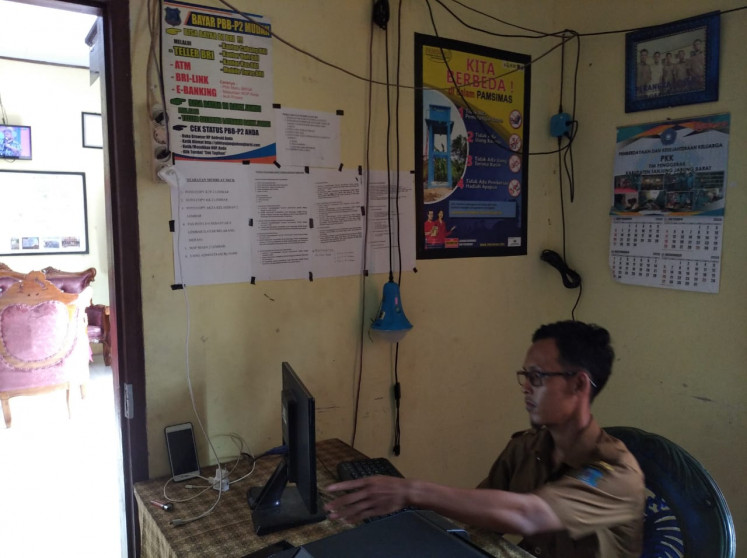

A village official operates a computer and charges his smartphone in Sungai Kayu Aro village using solar-generated electricity. The village used to run on diesel generators that only provided enough power for four light bulbs per home. (JP/Jon Afrizal/epost-robot)However, Sutiman said the station’s batteries wore out six months ago, cutting the electricity time to 12 hours. The village has asked the provincial energy agency to make repairs but have yet to see results.

“Residents will, of course, greatly benefit if PLN can bring in 24-hour electricity,” he said.

He went on to say that, more than just adding new electronics, 24-hour electricity would enable children to study for longer and residents to use basic domestic appliances.

Electricity would also enliven village businesses, including warung (kiosks) and handmade mat makers, to supplement their main economy of rice, coconut and betel nut farming.

In its letter, the ministry’s electrification directorate general reasoned that PLN had the legal right as the power distributor for the 19 villages. It cited ministerial regulation No. 28/2012 that grants the company first try as the permitted power distributor for the regency, as well as for almost all of Indonesia.

“What can the energy agency do? The agency supports us but they’re being blocked by regulations,” said Bungo Dani project lead M. Yandi SH, also on Oct 25.

The Post contacted four directorate general officials, all of whom either declined or were not immediately available for comment.

However, ministry electrification director general Rida Mulyana previously acknowledged the need for private funding in electrification. He said on Feb. 6 that PLN could only finance one-fifth of the estimated Rp 11 trillion to electrify Indonesia’s last mile.

Read also: PLN can only fund one fifth of $803m needed to power isolated regions

Not an isolated case

SUN and Bungo Dani are not the only private players that have experienced bureaucratic hurdles. Developers PT Akuo Energy Indonesia (AEI) and PT Listrik Vine Industri (Electric Vine Industries) have faced similar problems while trying to electrify remote villages in East Kalimantan and Papua, respectively.

In 2016, AEI began seeking area electrification permits to build solar mini-grids in three remote villages in Berau, East Kalimantan, a major coal-mining province. The 1.2 MWp system would bring 24-hour electricity for 400 homes that previously relied on pricey diesel generators.

AEI managing director Refi Kunaefi said the company secured the permits after following the ministry’s recommended tariff of Rp 1,400 per KwH, in line with base electricity tariffs, but lower than the initially proposed Rp 1,800 – Rp 2,000 per KwH.

“We aren’t making any money from our operations. These three years, we’ve been making operational losses,” he said. “We consider this the cost of learning to enter the industry."

Many global institutions have, over the past few years, criticized government policy for crowding out private investments in clean energy projects for remote villages. These institutions include the Asian Development Bank, United Nations Development Program (UNDP) and, most recently, the International Energy Agency (IEA).

Read also: Regulatory reform key to post-pandemic green energy investment, IEA says

The government did respond with several regulatory relaxations yet “private investment in renewable energy still remains abysmal and rural electrification is yet to attain universal electricity access,” wrote the UNDP in a 2018 report.

The main problem was that PLN’s low base electricity tariffs, which are heavily aided by electricity and fossil fuel subsidies, did not meet economically with privately funded projects, explained Indonesian Renewable Energy Society (METI) chairman Surya Darma.

The government’s populist preference to keep on-grid electricity prices as cheap as possible, down to Rp 415 per KWh, maximizes public affordability but, as experts point out, makes privately funded, green energy projects financially unsustainable.

“There is unfair treatment between renewables and fossil fuels,” said Surya.

In the Berau case, AEI, a subsidiary of France’s Akuo Energy, was fortunate enough to have a grant from Millennium Challenge Account (MCA) Indonesia, a United States-based development aid agency, that covered most of the stations’ capital costs.

Refi also said the company secured approval from PLN’s regional office before approaching the energy ministry. PLN confirmed it did not plan to electrify the villages within the next five years.

Success story: Akuo Energy Indonesia's (AKEI) 414-kilowatt (KW) solar-hybrid mini grid provides 24-hour electricity for Teluk Sumbang village in Berau, East Kalimantan. (rian/humasprovkaltim/epost-robot)Former energy minister Ignasius Jonan once said in 2018 that the ministry did not greenlight a solar mini-grid project in Papua because its tariffs were too expensive at Rp 10,000 per KwH. “Would the public want to buy the electricity [at that price]?” he asked rhetorically.

Read also: Govt yet to agree to Engie’s energy project in Papua

The project was that of Electric Vine Industries and French power utility Engie SA, which signed a $240 million deal in 2017 to build such grids for 3,000 villages across Papua, the country’s most impoverished and out-of-reach region. The deal would provide 24-hour green electricity.

The plan has yet to go through. Adaro Power, a subsidiary of coal mining giant Adaro Energy and a 25 percent shareholder of Electric Vine, confirmed the ongoing process.

"Many challenges remain in its implementation but Adaro continues communicating with PLN," said Adaro Power deputy president director Dharma Djojonegoro in a written response to the Post on Wednesday, adding that the company was “studying all of the aspects of a solar-powered mini electric system”.

The government’s low-tariff policy also strains PLN’s finances. The company needs to raise tariffs by over 30 percent “to sustain operating cash flow — a level that would surely test public approval,” wrote the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA) in a recent report.

Going forward, Refi and IESR’s Fabby said that private-PLN partnerships were key to sustainably electrifying Indonesia. They suggested green electricity subsidies, availability funding and viability gap funding, among the possible solutions.

Echoing the two experts, the IEA wrote in a recent report that, with COVID-19 relief programs straining public financing, “mobilizing new private sources of finance, especially for renewables, will be critical” in providing green electricity across Indonesia.

PLN just about enters the 19 villages

Despite PLN's size, electrifying the 19 villages in Jambi was no walk in the park for the company. The villages were only accessible via narrow dirt roads and soft, spongy, peatland, separated from Kuala Tungkal by a wide river.

The power company spent months securing the land for the powerlines, which needed to cross property owned by PT Wirakarya Sakti, a vast pulpwood supplier for giant paper producer Asia Pulp and Paper (APP).

In total, PLN had to build 400 km of power lines and 124 substations to connect the villages to “excess power” from PLN’s regional grid and from two gas-fired power plants (PLTMG) with a combined capacity of 15.2 MW.

PLN officially completed connecting the villages on Nov. 12, four months later than planned and at Rp 135 billion, but raising Jambi’s electrification ratio from 96.7 percent to 99.6 percent, just above the national average, according to a company statement.

“[Electrification] is within PLN’s legal authority,” said green sociopreneur Tri Mumpuni. “But the biggest issue is that PLN does not have the power to enter remote villages.”

Read also: Electrifying Indonesia's last stretch is tough work

Spurred by the law, the government and PLN raised Indonesia’s electrification ratio from 67.2 percent in 2010 to 99.9 percent in July 2020. The government aimed to achieve 100 percent this year but delayed it to 2021, because of project delays impacted by the COVID-19 outbreak.

Achieving 100 percent electrification in Indonesia, the world’s fourth-most populous country, will also significantly contribute toward achieving UN Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) number seven on universal electricity access for the whole world by 2030.

And yet PLN struggles in financing grid expansion into the last mile as it throws cash and capital into developing new coal-fired power plants (PLTU), despite a lingering power overcapacity, particularly in the Java-Bali region, at the behest of President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo’s ambitious 35-gigawatt (GW) expansion program.

PLN Kuala Tungkal head Rizki Tungguan said the company had to bring-in – or more precisely float-in – expensive, 13-meter-high, steel poles to allow it to electrify 19 villages in Jambi, as regular concrete poles could not stand in the area's soft, spongy, peatland. (PLN/epost-robot)Read also: COVID-19 hits already struggling power firm

The government has had to allocate Rp 9.6 trillion from state coffers to finance new PLN power lines and substations next year. However, PLN estimates that the capital injection falls short of meeting Indonesia’s power infrastructure targets that could amount to Rp 15.2 trillion.

Read also: PLN to receive Rp 9.6t to build power infrastructure

Furthermore, PLN’s grid is not without limitations. PLN Kuala Tungkal head Rizki Tungguan told the Post that, even though the infrastructure was ready, the company has yet to channel electricity into the 19 villages due to the ongoing gubernatorial and regency elections.

“Everything is on hold. We don't want to be politicized,” he said on Nov 3.

He also acknowledged that PLN’s grid could not meet the regency’s electricity needs. Thus, his office was negotiating with PT Lontar Papyrus Pulp & Paper Industry, also part of the APP group, to spare 3 MW from a privately owned power plant for Tanjung Jabung Barat.

“Electricity has been a chronic issue here,” said the regency’s energy agency head, Suparti, noting that even Kuala Tungkal regularly faced blackouts.

According to agency data, Tanjung Jabung Barat’s power demand is 21 MW, comprising 12 MW from areas below the river, including Kuala Tungkal, and 9 MW from above the river, including the 19 villages. In comparison, Jakarta’s demand is 5,000 MW during the day.

The regency administration wanted to build a PLTU to meet demand but “it hasn't been done because of environmental impact concerns,” added Suparti.

Bungo Dani and SUN have reached out to the energy ministry to reconsider letting them build the solar mini grid but to no avail.

“It’s like PLN is being forced to electrify the villages. Would it not be better to reconsider?” said SUN’s Verry, recollecting the companies’ plea to the energy ministry.

He noted that this was the startup’s first time applying for an area electrification permit. He said PLN had, otherwise, been quite cooperative in other projects and that regulations were quite attractive.

The two companies’ confidence took another blow in early October, when news spread that State-Owned Enterprises Minister Erick Thohir requested energy minister Arifin Tasrif to limit issuing area electrification permits “considering PLN’s operational and financial condition”.

The letter, a photo of which was leaked to the press, also asked the energy ministry to adjust PLN’s electricity procurement plan (RUPTL) to existing power demand. It did not mention renewables.

“That automatically makes our opportunity smaller,” said Bungo Dani’s Yandi of the news.

--Jon Afrizal contributed to this story

The article is funded with AJI Journalist Fellowship Program 2020