Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsEquality before the law: Are some more equal than others?

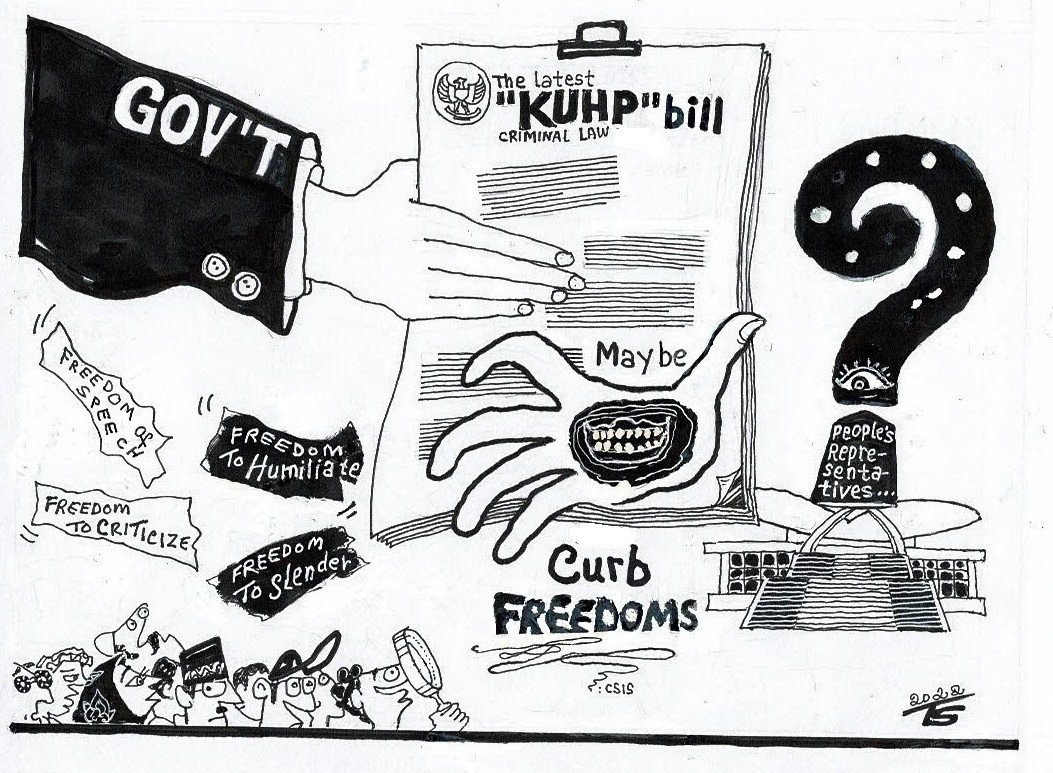

The latest draft of the Criminal Code (KUHP) sounds a deep and visceral warning that passing it as is will lead to the return of an authoritarian regime in Indonesia.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

I

f the House of Representatives endorses the draft penal code in its current form, it will formally create a class of the ruling elite in Indonesia that is separate from the rest of the nation and will enjoy many privileges, including the way the law treats them.

The draft code seeks to criminalize insults, not just against a sitting president and vice president, but also against anyone in government, meaning in the executive and legislative branches, and the judiciary including law enforcement agencies.

Human rights groups say that the term “insult” is vaguely if not broadly defined in the draft code, and that the related articles could be used to suppress criticizing the government. The draft contains other articles that human rights groups have found problematic. These would make the new code worse instead of better than the existing one, which the government inherited from the Dutch colonial regime.

If the House ignores the mounting public opposition and endorses the draft code, as it intends to this month, it will mark the beginning of Indonesia’s return to authoritarianism. The right to criticize the government, an important element in any functioning democracy, will be endangered. We have been here before: For over 30 years under Soeharto until just before the turn of the millennium, criticizing the regime and all its apparatuses landed you in jail, or worse, got you killed.

Turning the ruling elite into a social class in a democracy reminds us of the pigs in George Orwell’s dark, classic novel, Animal Farm. After the animals rebel against the farmer and seize control, the farm is divided into clusters of different animals, and the pigs become the ruling group. As they begin to enjoy power, they create privileges for themselves and shields against criticisms as their reward for leading the farm. “All animals are equal, but some animals are more equal than others,” says their commandment.

There is nothing wrong with trying to eliminate or reduce the number of insults that we read and hear everywhere, especially in today’s internet era. Social media platforms are full of insults, many degrading and dehumanizing, if not oppressive, and some could even be seen as inciting violence. We really need to do something about it, both online and offline.

Internet platforms are trying to clean up their act but have not been very successful, so governments around the world have been trying to rein in these companies to take more stringent control over digital content.

In an ideal world, we could do with fewer insults or none at all. But in practice, eliminating them outright could trample on the right to free expression. Article 19 of the International Covenant on Political and Civil Rights recognizes the limits to free speech when it obstructs other human rights. Some insults could be categorized as hate speech, and should be banned.

But this is not the kind of insult that the drafters of the Criminal Code have in mind. They are more concerned about protecting the honor and dignity of the president, vice president and everyone else in government.

In their defense, at least the drafters invoked the primus inter pares principle as regards the president and vice president; that they are first among equals because they hold the highest public office. But as the public debate focused on whether the country’s president and vice president deserved special treatment, they surreptitiously inserted articles that extended this protection from insults for everyone else in all three branches of government.

Of all citizens, lawmakers should be the last to enjoy this privilege. Given their work, they should not be beyond criticism. They are public servants who make decisions and laws for the nation and its people. There are bound to be mistakes and shortcomings along the way, and the people they serve have the constitutional right to express their criticism, even anger, if the legislation harms them.

If the penal code drafters are really concerned about the hurt and harm that insults can cause, then the protection should be given to all citizens. If that is impossible, then the protection should be extended to the most vulnerable groups in society as defined by race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, gender and other defined criteria.

The ruling class needs no protection. They are already in a position of power and enjoy the many privileges that come with those powers. Rather, they need to be kept in check so they do not misuse or abuse their power.

Indonesia is not a constitutional monarchy. Drawing comparisons with Thailand or Japan, as one proponent of the article on protection from insults explained, is simply misguided. As a republic, and a democratic one at that, requiring the ruling elite and public servants to be open to public criticism would be one way for them to be accountable to the people they lead and serve.

In a democracy, honor and dignity are things that citizens who hold public office must earn, just like trust. They are not qualities that automatically come with the job.

The latest draft of the penal code appears to be a clear attempt by the nation’s ruling elite to shield themselves from criticism and entrench their power over society.

Indonesia has struggled for nearly eight decades since achieving independence in 1945 to come up with a contemporary version of the Criminal Code, and one that it can proudly call its own. The existing code, enacted in 1918 by the Dutch colonial government, has long passed its use-by date.

But if we allow the draft penal code in its current iteration to be passed, it will be a gross tragedy for Indonesia and for our democracy, and it will probably take another 80 years to undo. History and all future generations will never forgive us for paving the way for the return of an authoritarian government.

***

The writer is a senior journalist at The Jakarta Post.