Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsHealth or economy? Making the best impossible decision in the face of COVID-19

The Indonesian government can still grow the economy without risking too many lives.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

W

hen Indonesia, Southeast Asia’s largest economy, first began grappling with COVID in 2020, its government was widely criticized for choosing to save the economy over people’s lives in its COVID-19 policies.

Initially, the government shut down businesses – including restaurants, malls, transportation and tourism – when the pandemic started in March 2020. However, under its “new normal” policy, the Indonesian government allowed businesses to resume operation, putting people’s lives at stake, relatively early in the pandemic in mid-2020.

Yet the result was still disappointing for the economy. Indonesia’s economy contracted by 2% in 2020, the highest shrinkage since 1998.

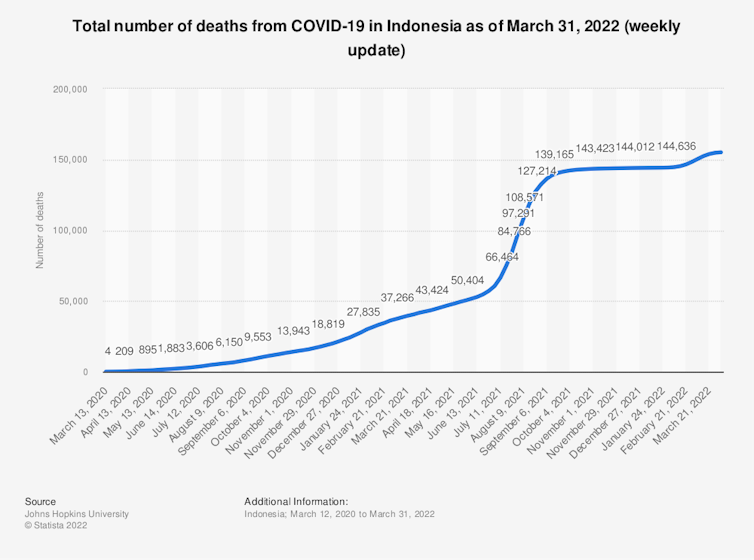

The country also lost 22,000 lives during the year. Due to the Delta variant outbreak, fatalities soared to around 144,000 by the end of 2021, putting Indonesia among the countries with the highest mortality rates.

Our recent research offers an answer to this health-versus-economy dilemma. We show that a middle-of-the-road policy that saves both business and people’s lives is possible.

By combining two models calculating the impacts of the pandemic on economic activities and on public health, we found a scenario in which the Indonesian government can still grow the economy without risking too many lives.

Under the scenario, the government could have reduced the number of deaths close to 2,000, but at the cost of only around 5% of gross domestic product (GDP, a measure of economic performance) in the same span of time.

But how?

Building the right approaches

We combined health and economic models to generate six possible scenarios connecting health and economic policies.

Both models represent the evolution over time and multiple regions of either an infected population or economic output.

The study links two government interventions: border restrictions and public health policy - both are expected to curb transmission but negatively affect the economy.

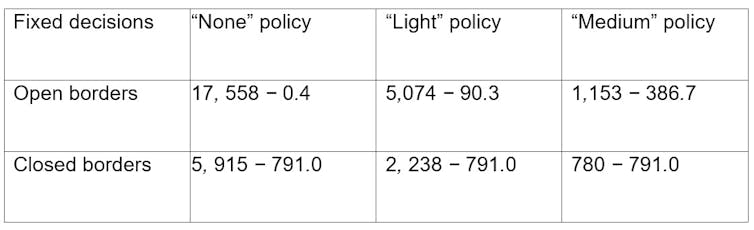

We first consider simple scenarios in which all borders are open or closed during the entire time horizon or there are three levels of public health policies being implemented: none, light and medium.

“None” means a complete absence of restrictions to contain the transmission of the virus. This policy exhibits the highest infection rate but with no changes to economic demand or production levels.

A “light” health policy would restricts the services, trade and hotel sectors, thus reducing the transmission rate.

Finally, “medium” represents a harsher but more effective health policy. It places restrictions on construction, manufacturing, transport and communication, and increases the severity of restrictions on services, trade and hotels.

By closing the border and maintaining restriction only to service and tourism sectors, the government could reduce the number of deaths close to 2,000. This will cost only around 5% GDP in the same span of time.

Under the loosest plan (open border with health policy set to “none”), the total number of fatalities is projected to be 17,558. At the same time, the economic shortfall is relatively small. The economic cost is non-zero because of workers’ absenteeism exposed to COVID-19.

Health and economic objective values under different scenarios, where all intervention policies and border restrictions are fixed in each scenario as an input. The first number in each cell shows the value of the health objective (total number of deceased), and the second number shows the value of the economic objective (in trillion rupiah).

On the other hand, under the strictest plan (closed border with medium policy), the model estimates that 16,767 lives could be saved. This plan imposes a massive cost to the economy: around 10% of GDP over a year.

What these mean?

These numbers give a range in which the model’s health and economic objectives can change.

The study used the combined model to propose plans that save lives but with lower costs for the economy and evaluate the various possible trade-offs between these two goals.

The table also suggests that closing borders incurs a considerable cost to the economy, regardless of imposed health policies.

Keeping borders open and setting the light policy is almost as effective as closing borders but imposing no policy in saving lives.

However, the former imposes a significantly smaller cost on the economy. This shows the significance of assessing public health policies in regions on the number of deceased individuals.

Similarly, when the medium policy is imposed in all areas, the effectiveness of closing borders in saving lives is almost the same as keeping them open, but the economic cost is roughly halved.

The study also evaluates that heavy governmental intervention – a closed border and medium policy – can save around 35,000 lives in a year, but that in the worst case it would incur a substantial decline in the economy (around 10% of the GDP in our model).

The model also reveals that many other solutions involving more parsimonious public health measures offer different trade-offs, leading to more lives being saved.

Border closure and the medium policy are policy options that are likely to be implemented. However, this policy must be supported by ensuring activities – especially in services, trade, hotel sector and food security – comply with health protocols.

At the same time, the government should provide a social safety net for individuals and businesses that are negatively affected.

One can argue that the pandemic has subdued, with relatively mild Omicron variant symptoms and widespread booster vaccines. But it is never too late to learn and prepare the best scenario for what is yet to come. This study shows that that we can provide alternatives to health-economy dilemma related to COVID-19.

---

This research was funded by the Australian Government through the Australia-Indonesia Centre under the PAIR program.

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. The Australia Indonesia Centre supports The Conversation Indonesia in the production of this article.![]()

Sri Astuti Thamrin, Ph.D/ Dosen Universitas Hasanuddin, Universitas Hasanuddin; Andreas Ernst, Professor of Mathematics, Monash University; Pierre Le Bodic, Senior Lecturer, Monash University; Salman Samir, Lecturer in Department of Economics, Universitas Hasanuddin, dan Sudirman Nasir, Associate professor, Universitas Hasanuddin

Read the original article.