Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsWhen no one leads, everyone loses: Breaking stalemate in industrial decarbonization

“We are not only responsible for what we do, but also for what we do not do” – Moliére

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

E

very delay in decarbonizing our industries is paid for in climate disasters, worsening air pollution, and disrupted livelihoods. In 2021, Indonesia suffered over Rp 100 trillion in climate-related losses, from flooded factory floors in Bekasi to paralyzed logistics routes in Central Java. As climate impacts intensify, industries are not just contributors to the crisis but also the victims and ones that are increasingly exposed to these risks. The longer we delay the transition, the greater the risk of normalizing disruptions that erode our competitiveness and cause irreversible damage

Meanwhile, the climate clock is ticking. The IPCC’s Sixth Assessment Report makes it clear: to keep global warming below 1.5°C, the world must cut emissions by 43 percent by 2030 and reach net zero by 2050. But current trends point toward a 3°C warming trajectory, a scenario that would render many coastal cities, farmlands, and industrial hubs increasingly uninhabitable.

Indonesia’s industrial sector sits at the heart of this issue. It is the largest source of our national emissions, responsible for 34 percent of Indonesia’s total greenhouse gas output. At the same time, industry commands capital, shapes production and consumption patterns, and anchors the broader economy. This dual role, as both emitter and growth engine, presents a unique opportunity to realign our economic resilience with environmental sustainability through industrial decarbonization.

The case for urgency isn’t just environmental. It’s economic, political, and deeply personal. The costs of inaction are increasing over time, be it in the form of health risks, infrastructure losses, stranded assets, and lost competitiveness. Failing to act decisively today means higher costs, more disruption, and fewer options tomorrow.

A vicious cycle of delay

Despite increasing pressure to decarbonize, industries are struggling to keep up with the scale and speed of the change required. Businesses are navigating an increasingly complex set of expectations, from measuring and reporting their emissions to developing low-carbon strategies and redesigning their production processes. All while racing against time, budget constraints, and profit uncertainty.

No wonder many are holding back. Small and medium enterprises (SMEs), lacking resources and risk appetite, wait for larger companies to pave the way. Large companies, lacking stable policy signals and financial incentives, wait for export-oriented companies to pioneer. Export-oriented companies, facing demands from developed markets, hesitate to act without strong national policies that offer protection and support. While the developing nations, pointing toward the global historical emissions contribution, expect emerging economies to share more of the burden. The result is a global stalemate, a culture of “wait and see” where everyone is waiting for someone else to move first.

This collective inaction attitude is increasingly costly. The longer companies delay their action, the greater the risk. Including being locked into outdated technologies, having accumulated stranded assets, or facing sudden regulatory shifts that can disrupt operations and trading. Brand value is also on the line. As sustainability becomes a mainstream expectation, laggard companies risk a backlash, either from their conscious consumers, investors, or even employees.

Breaking the stalemate

Industries must start somewhere. As the saying goes, “All roads lead to Rome.” The question is: among those paths, which one should be prioritized?

There are two primary categories of decarbonization strategies: abatement and removal. Abatement strategies aim to prevent emissions from being released in the first place, while removal strategies focus on capturing emissions after they occur, either through nature-based solutions or carbon capture technologies. While both are necessary to reach net zero, abatement must come first. Removal technologies such as carbon capture and storage (CCS) remain costly and energy-intensive, and their scalability is limited by Indonesia’s still-nascent regulations for carbon storage.

At the same time, the implementation of nature-based solutions can provide a premature sense of accomplishment. For example, companies may claim emissions have been offset by planting mangroves. While in reality, the actual carbon sequestration only occurs gradually over the course of 20 years, and only if the ecosystems are properly maintained and protected.

Within the abatement category, there are four main pillars: energy and material efficiency, process improvements, low-carbon electricity and electrification, and fuel and material substitution. Among these, energy and material efficiency should be prioritized. It is the most cost-effective, technologically mature and broadly applicable strategy across industrial subsectors from heavy manufacturing like cement to light manufacturing like textiles. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), energy efficiency measures alone can deliver over 40 percent of the emissions reductions needed by 2040 to stay on a net-zero pathway. Yet, these solutions remain underexplored and underfunded. Why? Because they are often seen as “too incremental”, lacking the allure of large-scale technology breakthroughs.

In reality, many of these efficiency upgrades, such as retrofitting boilers and optimizing heat integration and recovery, can yield immediate financial returns, with cost savings of up to 20 percent and common payback periods of less than three years. These are not just a win for the climate, but also a smart and forward-looking business decision.

At the same time, industrial actors cannot shoulder this transition alone. Climate change is a systemic challenge, and systemic problems demand systemic solutions. This means governments must step up to create the enabling environment that industries need.

First, the government must provide targeted incentives, such as carbon pricing, tax breaks for green investment, subsidies, and concessional finance for high-risk innovation.

Second, build demand for green products, either through public procurement policies, eco-labeling standards, consumer awareness campaigns and trade policies that reward low-carbon production.

And third, establish strong regulatory push/signals, including imposing an emissions-reduction target or performance standard, mandatory emissions reporting and a time-bound road map for phasing out high-emitting technologies.

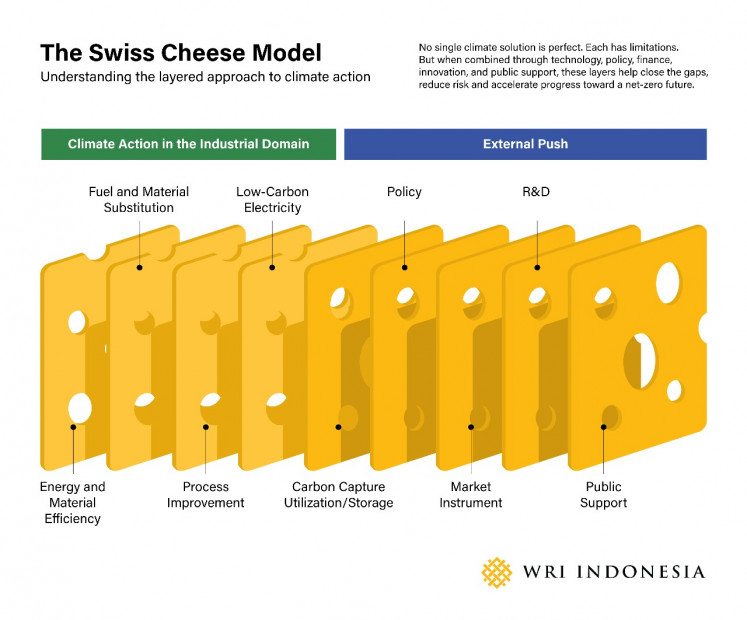

A useful analogy is the Swiss cheese model of risk management. The idea is simple: no single layer of defense is perfect, each has holes, but if enough layers are stacked properly, the holes do not align, and disaster is averted. The same principle applies to climate action. Efficiency measures may not capture all emissions, but when combined with robust policy, market instruments, R&D investment and societal pressure, they can collectively close the gaps. To break the stalemate, someone must move first. Let it be the one who recognizes that leadership is not about waiting for certainty but about creating it.