Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

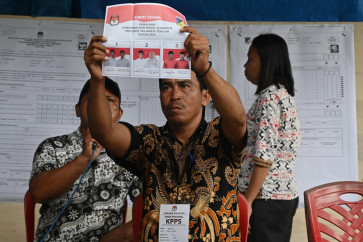

View all search results75 years on, Indonesia grapples with entrenched corruption

Corruption remains an intractable issue to resolve in Indonesia after 75 after years of independence.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

Corruption remains an intractable issue to resolve in Indonesia 75 years after the country became independent.

The present-day antigraft campaign has been largely spearheaded by the Corruption Eradication Commission (KPK), which was established in late 2003 because of low public trust in the police and the Attorney General's Office.

The KPK was quick to uncover two corruption cases throughout its first year of operation. In 2018, it uncovered 199 corruption cases, the highest yearly number of cases the commission has investigated.

Yet corruption persists. Many modern-day scholars believed that it has become an inseparable part of Indonesia’s culture. A similar view was shared by the country's first vice president, M. Hatta, in 1974, according to history magazine historia.id.

Recent pollsters also said that Indonesians were growing more permissive toward petty corruption, a trend experts fear could motivate major acts of corruption.

In early July, Coordinating Political, Legal and Security Affairs Minister Mahfud MD denied such a notion, saying that corruption was merely an individual crime and did not represent Indonesia’s identity.

“Indonesia has been known as a nation that upholds moral values since the old time, so corruption is clearly not a part of our culture,” he said.

Looking further through history, corruption seems inevitable

Scholars found that corrupt practices were ingrained in Indonesian society long before independence.

In a chapter of a 2013 book titled Korupsi Mengorupsi Indonesia (corruption and the corrupt in Indonesia), State Islamic University (UIN) Syarif Hidayatullah scholar Sukron Kamil wrote that bribery had been common since at least the 17th century in the Mataram Sultanate in Central Java. It said the sultanate often gave top positions in its government to those who paid the largest bribes, regardless of their ability.

A paper titled “Cultural strategy to eradicate corruption in Indonesia” by Airlangga University scholars Listiyono Santoso and Dewi Meyrasyawati and published in the June 2015 edition of The Political Review also depicts the history of bribery.

It cites a 1986 study conducted by late Institute of Economic and Social Studies and Development (LP3ES) historian Onghokham, which found that ruling dynasties of many kingdoms during Indonesia’s precolonial period often misused assets of the kingdoms to buy loyalty and allegiance from regents and war commanders.

The paper says the longtime corrupt practices in the country have caused the public to accept corruption as a common practice, internalizing corruption as a way of life. “But still, corruption is a thorn in the flesh of Indonesian culture,” the paper said.

Ups and downs of graft eradication after independence

In the early years of independence, Indonesia realized it should leave behind corrupt practices inherited from the past and move toward modern and clean governance.

According to Korupsi Mengorupsi Indonesia, the first anticorruption measure was introduced by the army through a string of regulations from 1957 until 1958 -- one of which prohibited officials from misappropriating state budget funds, abusing power for personal gain and causing state losses.

The fight against corruption continued in the early days of the New Order regime in 1967, when then-president Soeharto established a corruption eradication team to bring graft offenders to court. But students and news outlets at the time criticized the team for its lackluster performance.

As a result, Soeharto replaced it with another short-lived team called Komisi Empat (Commission Four) in 1970, before signing a 1971 law that penalized those causing state losses for self-enrichment to a maximum sentence of life imprisonment, the book said.

Even so, nepotism and corruption mushroomed under the authoritarian regime.

After Soeharto’s 31-year regime ended following massive protests and rioting in 1998, students and civil rights groups demanded that policymakers issue stronger anticorruption laws. This resulted in the enactment of a 1999 law on corruption eradication and later a 2002 law that mandates the establishment of the KPK.

All the efforts eventually bore fruit, as evidenced in Indonesia's improvement in Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index, from a value of 19 in 1995 to 38 in 2019. The index uses a scale of 0 (very corrupt) to 100 (clean).

Despite the upward trend, Indonesia hit rock bottom in 1999 with 17. It also saw a decline from 24 in 2006 to 23 in 2007 when corruption courts acquitted some graft defendants, according to Transparency International Indonesia (TII).

The fight against corruption faced another roadblock when lawmakers amended last year the 2002 KPK Law and stripped it of several authorities that once made the KPK a superior law enforcement agency in the country.

Challenges ahead

Much of the hope for rooting out corruption now rested with the willingness of political elites in the country to leave them behind and be role models for the public, sociologist Nia Elvina said. She cited sociological research showing that Indonesian society tended to follow “patron-client relationship” patterns, in which, according to her, the public would imitate everything their leaders did.

Wawan Suyatmiko of TII said law enforcement agencies should apply stern measures against graft offenders to deter corruption.

KPK commissioner Nurul Ghufron said, however, it should not solely depend on law enforcement, but also through political party- and campaign-financing reform that could narrow the chances of those in power to commit corruption. He blamed rampant corruption on costly elections.

Lawmakers, regional leaders and councilors represented the largest number of individuals investigated by the KPK between 2004 and May 2002, with 417 individuals, or 34.6 percent of the total 1,203 individuals

“Due to such a political system [that lacks accountability], we now have a tough job to ensure that our law enforcement is a deterrent to corruption, and at the same time to instill an anticorruption culture in the general public,” Nurul said. “That’s why we are now focusing more on corruption prevention and public education.”