Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsListen up: Music for the internet age

Those of a certain age might remember the days of making mixtapes or burning CDs to share music, back when playing them meant lugging around a clunky boombox or player.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

This year around, with the pandemic in full swing, music offers comfort.

In the age of Spotify, SoundCloud and smartphones, music is readily available online.

With just an internet connection, people can stream songs by their favorite artists from the second they are released, while at the same time just about everyone can upload their own music, whether it is original content, covers or remixes.

Clearly there has been a shift in the ecosystem, where the availability of free music coexists with a more conventional storefront, both digital and physical.

Others have taken a different approach, such as Yogyakarta-based label Yes No Wave Music.

Founded in 2007 by interdisciplinary artist Wok The Rock, Yes No Wave is described as a non-profit music label that distributes musical works to the public as a “gift-economy” act – an experiment in free legal music to support an open-sharing culture movement.

In an online discussion hosted by Nusasonic, Wok The Rock – the stage name of Woto Wibowo – said that while he was open to a wide range of genres, ultimately it came down to whether the artists were willing to have their works distributed for free.

Future of music: Hosted by Nusasonic, the discussion featured heads of notable indie labels such as Saphy Vong (top left; Chinabot, London), Wok The Rock (top right; Yes No Wave Music, Yogyakarta) and Salem Rashid (down right; Bedouin Records, Bangkok). (Courtesy of Nusasonic/-)The label’s stance, he explained, came from his own view that the current music industry model did not work in Indonesia, with rampant piracy up until today along with a litany of other issues.

“Even for big mainstream artists, once their music is not favored anymore, then the labels just leave them. [...] There are a lot of stories about major artists that used to be very rich but are now very poor and die on the streets.

“For me, the music industry doesn’t really work – it’s not helping artists. That’s why I wanted to start a label that’s based as a cultural movement or even a political movement,” he said.

Wok also noted the Indonesian culture of sharing and helping each other, which he then applied to a technological platform based on sharing.

Salem Rashid, creative director and founder of the Bangkok-based Bedouin Records, observed that the Indonesian music scene had “uncompromising” support from fans, whereas Thailand’s was less centralized and unionized.

“In terms of sharing music for free, the first two years I only did physical releases and the digitals we would share for free. It turns out some of the artists themselves started asking for their music to be on specific platforms and I haven’t decided whether it is a good idea to switch over to streaming platforms because we haven’t made more than US$20,” he said.

Still, Rashid noted that in order to be truly successful in that regard, the label must keep in mind what the artists’ visions are.

As for his own label, location does not change the way he runs things. Though Bedouin Records was founded in London in 2014 and only settled in Bangkok for a little more than a year, the label is run entirely from his laptop and phone.

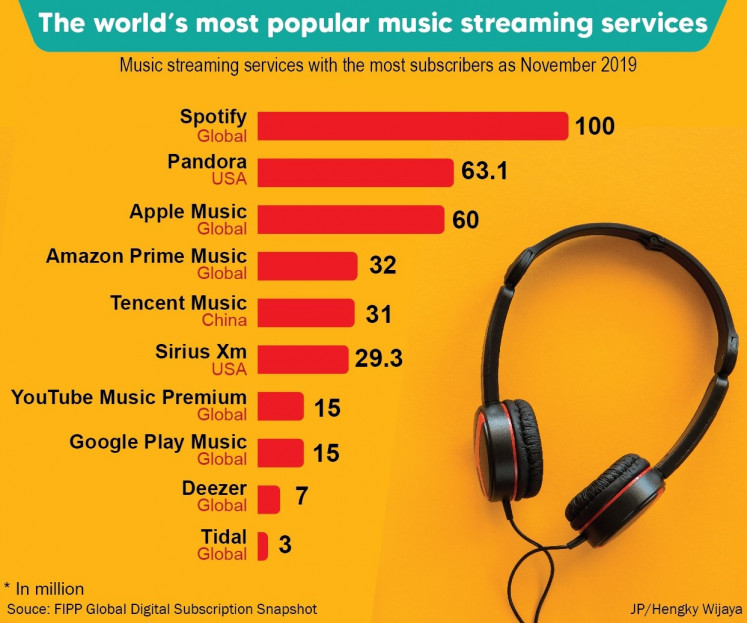

On top: Spotify remains the world's most popular streaming services in this November 2019 data. (Courtesy of FIPP Global Digital Subscription Snapshot/-)With social media being one of the main powerhouses in modern culture, it is no surprise that promoting and sharing music will also benefit greatly from the exposure, with major names like Lady Gaga or Ariana Grande teasing new releases and snippets to send their fanbases into a tizzy.

Wok acknowledged the widespread usage of social media during his earlier days, mainly through the now-defunct Friendster.

Back then, prior to SoundCloud and Bandcamp, social media was the only platform to promote new releases, helped by the fact that Indonesians were very much into social media.

“It also does not cost much – I don’t have to print posters, for example. At the beginning I used mailing lists and it really worked in reaching the audience,” he explained, although he also noted the increasingly raucous nature of the Indonesian social media atmosphere.

Also of note are Wok’s unique methods of sharing: back when internet cafes were all the rage, he would copy the files onto computer desktops so that guests would take notice of the music sitting conspicuously on an otherwise normal desktop.

Another one is when selling merchandise at a gig. While the merch is obviously for sale, he would have a computer at the ready so that fans can download the music for free.

On the other hand, London-based sound artist LAFIDKI aka Saphy Vong, founder of the Asian music platform-collective Chinabot, mainly uses social media as a newsletter.

While he acknowledged that he struggled with platforms like Twitter and was not interested in TikTok, Vong used Facebook a lot and was now starting to get into Instagram.

“I started a Bandcamp page before having a website, which was really helpful. But I’m from this MySpace generation, so I don’t even know much about Spotify. I think Bandcamp is the fairest platform,” he said.

Meanwhile, Rashid started out by using mailing lists and distribution channels as a producer in the United Kingdom, but along the way he had a revelation that the method was elitist, as not everyone was an industry insider and would only be hearing them on social media.

Still, he had his own words of advice for artists he worked with who were concerned about the amount of likes they were getting.

“You should never think of your value and what you do according to an algorithm of your online presence. That’s not important.” (ste)