Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsConstitutionalizing the Pancasila presidency

Prolonged tenures of the executive have been typical of corrupt governments in burgeoning republics throughout the 20th century

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

T

he question of extending presidential term limits under the Constitution for President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo to contest the 2024 election has been circulating through news desks with some frequency of late, as recently as a July 7 article in The Jakarta Post.

Then, as if to cast a particularly mirthless shadow upon the question, on the same day, Haitian President Jovenel Moïse met his demise by a band of assassins. Moïse was elected under peculiar circumstances, leading to some contention about the length of his term in office. Moïse not only remained in office after the constitutionally required date of Feb. 7 but also sought to potentially extend his presidency until 2026 through constitutional amendment.

While this approach had some international support, it may have cost Moïse his life and brought brutal injury to his wife.

This second-rate danse apache brings to mind the barbarities of the Dutch Rampjaar, in which the Grand Pensionary Johan de Witt and his brother Cornelius were murdered by an aggravated lynch mob of Orangists.

There was similarly a struggle for the power of the executive prior to that most sanguine murder. It was not unreasonable of de Witt to attempt to prevent another Stadtholder from the House of Orange, but this, too, cost him his life. Neither the office of Stadtholder nor Grand Pensionary were subject to term limits. After the Rampjaar, it was all but ossified that the office of Stadtholder would be de facto hereditary, and the Republic did finally revert to hereditary monarchy after a short existence.

The authors of the United States Constitution took express note of the Dutch record. In one letter responding to the outcome of the constitutional drafting, US icon Thomas Jefferson wrote, “What we have lately read in the history of Holland, in the chapter on the Stadtholder, would have sufficed to set me against a chief magistrate eligible for a long duration, if I had ever been disposed towards one.”

He was objecting chiefly to the absence of term limits for the US president. Luckily, then-president George Washington was determined to voluntarily relinquish the office of President, although he was under no constitutional obligation to do so.

The magnanimity of Washington’s retirement became an enduring cultural standard in the US, and so, de facto, a component of its Constitution. The US framers had depended upon a nearly Roman concept of personal and civic virtue in republicanism in the design of the US republic, and considered themselves fortunate to have had Washington available to model the Quiritarian citizen-servant for all future presidents.

Nevertheless, temptation was present, and term limits had to be constitutionally enacted by 1951, shortly after the prolonged presidency of Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Similarly, if the Indonesian President is to have a fair chance of modeling the principles of Pancasila, it is vital that term limits remain fixed in the Constitution.

Article 7 of the Indonesian Constitution permits no more than two five-year terms for the office of president. Nevertheless, Sukarno was able to appoint himself commander-in-chief of the revolution and president for life through a 1963 Provisional People’s Consultative Assembly (MPRS) decree. Soeharto followed suit. Under the pretense of sacred reverence for the letter of the Constitution, he was able to reign for 32 years.

Prolonged tenures of the executive have been typical of corrupt governments in burgeoning republics throughout the 20th century. Domestic corruption in combination with the exogenous influence of foreign nations exert an undue influence upon the virtues of a country, its people and its president.

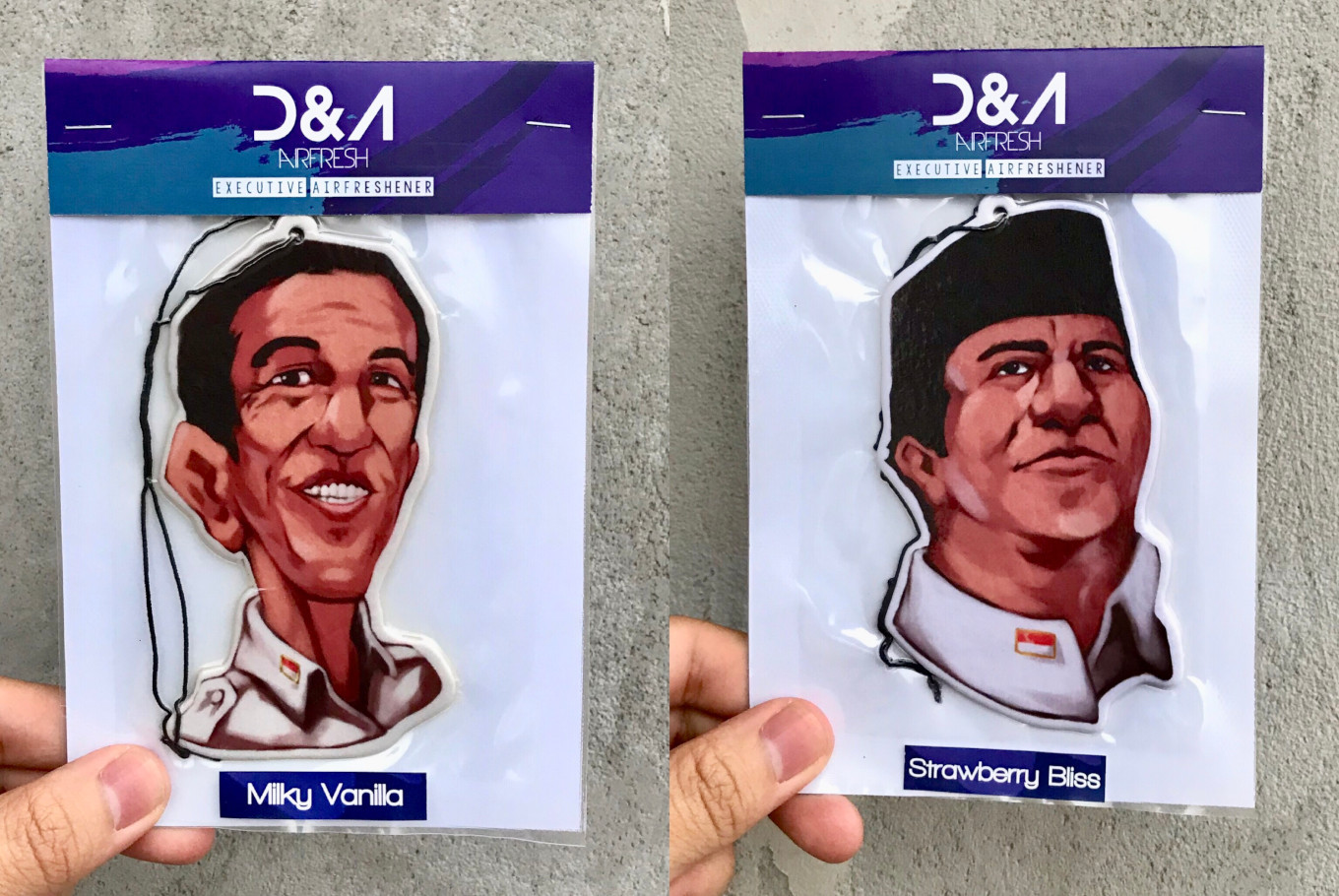

While a survey found 74 percent of Indonesians would prefer to retain term limits for the president, calls to relax or eliminate these limitations continue, along with talk of a Jokowi-Prabowo 2024 ticket, which was designed to forge good feeling, reduce polarization and increase stability. Yet this is to suggest that stability is increased by temporary political unions and the increase of public confidence in particular individuals, rather than in the increase of public confidence in the good sense of the republic that the Indonesian constituent designed.

Regrettably, however, the current partisan configuration of the MPR would make this process a piece of cake. The MPR consists of 575 members of the House of Representatives and 136 members of the Regional Representatives Council (DPD). Presently, only two opposition parties stand against the presidential coalition. The opposition commands only 18 percent of the vote, while the coalition government has nearly 82 percent.

Referring to Article 37 of the Constitution, a quorum of a mere two thirds of all 711 seats in the MPR, or 474 members, is all that is required to consider a constitutional amendment. Only 50 percent plus one member must approve the amendment, a mere 356 votes. In other words, the coalition government has far more than enough votes to pass the amendment and would require the attendance of only three members of the DPD or of the opposition parties in the House in order to achieve a constitutionally sufficient quorum.

Long-serving presidents undermine the people’s confidence in the capacity of their government to carry out – inevitable – transitions of power peacefully. They undermine the legitimacy of that government to international actors by giving the appearance of corruptibility.

This may as well be a signal fire to alert those corrupt actors abroad who would make their personal fortunes from the exploitation of Indonesian resources and lives. A corrupt bargain with a president-for-life is a better deal than one with a president.

Article 37(5), however, does suggest an alternative course of action. The unitary state of Indonesia cannot be amended without a new Constitution. The US Constitution contains a similar entrenchment. The people may not amend the US Constitution to alter equal representation of every state in the US Senate.

While it may be an uphill political battle, it would be theoretically possible to amend the Constitution so as to absolutely entrench the Article 7 term limit for the President against any possible amendment. This would instead signify a permanent confidence in the stability of Indonesian institutions and would reduce the possibility of corrupt usurpation of the government by forces foreign or domestic.

Caution would have to be exercised in the drafting of the entrenchment, however. In the US Constitution, the entrenchment against unequal representation in the Senate is not itself entrenched against amendment. It would be possible merely to remove the entrenchment by amendment and so then create unequal representation in the Senate.

This particular outcome is politically unrealistic in the US. However, as the Indonesian Constitution is comparatively easier to amend, it would be worth considering absolute entrenchment of presidential term limits.

Yet caution is always necessary. Should the Constitution become too inflexible by the entrenchment of too many provisions and the great weight of public opinion come to bear upon it, it may not bend but break.

***

Steven Amendola is a student at William and Mary Law School, US, and an intern at The Center for Constitution Study (PUSaKO) Faculty of Law, Andalas University. Ari Wirya Dinata is a lecturer and researcher at PUSaKO.