Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsHunger Tales: Art inspired by Indonesia’s food supply crisis

Art imitates life for the Yogyakarta-based Bakudapan food study group, as they bring their take on the politics behind Indonesia’s food supplies crisis to the 2021 Asian Art Biennial in Taichung, Taiwan.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

A

rt imitates life for the Yogyakarta-based Bakudapan food study group, as they bring their take on the politics behind Indonesia’s food supply crisis to the 2021 Asian Art Biennial in Taichung, Taiwan.

The players converged around the board game, keen to know where the next roll of the dice would go. Just as Monopoly participants can land on Chance or Community Chests cards, the participants in this game have an equal chance to end up on Deal or Phenomenon cards. These cards seem promising, until you read their dry, cynical messages.

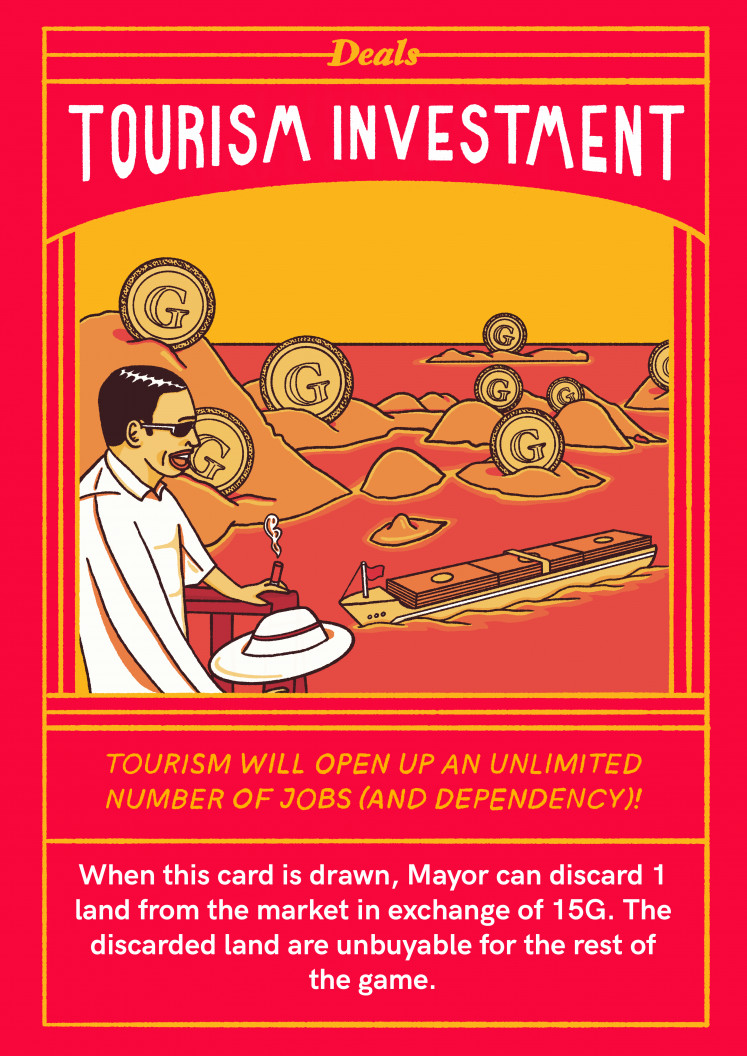

“TOURISM INVESTMENT. TOURISM WILL OPEN UP AN UNLIMITED NUMBER OF JOBS (AND DEPENDENCY)!,” one Deal card proclaims. “When this card is drawn, [the] Mayor can discard 1 land from the market in exchange for 15 Grand [as in thousands of rupiah]. The discarded land is unbuyable [sic] for the rest of the game.”

The Phenomenon cards are just as scathing.

“LACK OF WATER. WHERE DID ALL OUR WATER GO? OH RIGHT, TO THAT NEW CONSTRUCTION IN DEVELOPMENT,” said one Phenomenon card, no doubt alluding to droughts afflicting parts of Indonesia, as well as the draining of groundwater by high rise buildings in Jakarta and other Indonesian cities in recent years.

“When this card is drawn, each land owned by farmers can only produce 3 food per turn. The effect lasts[s] for 1 round.”

In the box: The box containing the Hunger Tales art piece. (Courtesy of Bakudapan) (Personal collection/Courtesy of Bakudapan)The Deal and Phenomenon cards are part of the “Hunger Tales”, an installation art piece created by the Bakudapan Food Study Group. The Yogyakarta-based collective’s work is making its debut in the wider world as Indonesia’s entry to the 8th Asian Art Biennial in Taichung, Taiwan, which runs until March 6, 2022.

The “Hunger Tales” is vying for the attention of art lovers throughout Asia along with the works of 38 artists and art collectives from 15 Asian countries, including India, South Korea and Biennial hosts Taiwan.

Themed Phantasmopolis to allude to late Taiwanese architect Wang Da-Hong’s 2013 science fiction novel Phantasmagoria, the exhibit “investigates the idea of ‘Asian Futurism’ and…how sci-fi topics and materials have been [...] represented in Asian modern and contemporary art,” noted the press release of Phantasmopolis, a portmanteau of the Greek words phantasma, meaning spectral, illusory, and polis. They are “artistic creations by contemporary Asian artists in response to urbanity, technologies and […] the pandemic.”

Filling the void

For Bakudapan, the “Hunger Tales” is the latest in their ongoing exploration of the food supply crisis since their founding in 2015. This is epitomized by the group’s name, which was based on the term bakudapa (meeting in Minahasan language) kudapan (snacks served during a meeting or visit in Javanese).

“The idea of making [“Hunger Tales”] came as…we [were] speculating about the food crisis…and how it has occurred within the context of Indonesia and globally. The food crisis…is rife with interests, stakeholders and victims of oppression,” said Bakudapan researcher Khairunnisa or Nisa. Her colleague Shilfina Putri Widatama agreed.

“We wanted to share these aspects of food politics with a bigger audience,” said the Gadjah Mada University Philosophy major. “Therefore, we came up with a board game that allows its players to role play as characters that take part in bringing about and ‘resolving’ the food crisis.”

Just as gamers in Monopoly play as business owners wheeling and dealing in real estate with one player designated as a banker, Hunger Tales players simulate farmers, wholesalers, middlemen, politicians and others who play roles in the food supply chain.

“We hope [through “Hunger Tales”,] we can understand that the crisis cannot just happen without our intervention. What this board game offers is an alternative perspective of the food crisis,” added fellow Bakudapan member RR ‘Roro’ Esty Wikasilva.

Stay gold: The cover of the Hunger Tales game. (Courtesy of Bakudapan) (Personal collection/Courtesy of Bakudapan)“These include how the goods itself are being brought to the market, how it commands high or low demand, or how some communities are having a food crisis while others are feasting,” said Shilfina, who noted that the public also played a part. “It is likely the way we live also contributes to the situation.”

This premise is shown in the cards labeled Social Unrest, as well as a card called Taxation. “RIOT IS THE LANGUAGE OF THE UNHEARD,” echoed the former. “WE LOVE OUR RICH MAYOR! LET’S MAKE THEM EVEN RICHER BY PAYING TAXES THAT WILL NEVER BE USED TO BENEFIT US,” exclaimed the latter. While the cards presumably lend those players simulating politicians with power over their opponents, these and other cards undoubtedly allude to the food crisis’ close links to political interests.

Heading into the dystopian abyss

One of the issues the “Hunger Tales” touches on is the ongoing dichotomy between urban and rural areas, which is represented as a mirage. It is also in line with the themes brought up by Phantasmopolis at their bleakest.

“[The Indonesian] government has always segregated between rural and urban areas. One of the main problems is how the government depicts a groundless idyll of houses with roofs and ceramic floors, or the daily consumption of rice,” Nisa said. The Gadjah Mada University alumnus in cultural anthropology called for solidarity with farmers who bear the brunt of the food crisis, a stance Bakudapan has long taken.

“The problems experienced by farmers are the impact of food policies that favor those in power. They continue to be weakened by the capitalist food industry, and the continuous maintenance of this system,” Roro reiterated.

Nisa also suggested a rethink of Indonesia’s national motto Bhineka Tunggal Ika (Unity in Diversity). “Indonesia has different climates, cultures and histories. We have to consider diversity, not unity,” she said. “The government’s systemic oppression [of diverse age-old traditions] has brought about the loss of indigenous wisdom. Rural areas have always suffered in the name of ‘development’ to meet the ideals [of urbanites] in the cities in justifying their accumulation of capital, by dispossessing [rural] people.”

Bakudapan noted that the COVID-19 pandemic aggravated the situation, as it did with other sociopolitical and socioeconomic crises, especially as the food that is found in the market is determined by food politics and policies that favor investors.

“COVID-19 shows how fragile our food system is, because it cannot support daily food necessities fairly and equitably. The food crisis is happening on a daily basis locally,” Roro said. “Land grabbing, [runaway] development, the disappearance of indigenous knowledge of seeds and local foods are affecting food production and consumption. The pandemic’s restrictions and regulations make some communities even more vulnerable.”

Most of all, Nisa warned against the rampant politicization of the food supply crisis if rampant exploitation of food sources is left unchecked. “The food crisis is [more than] a matter between urban and rural [inhabitants]; all of us can become the victims of food politics, and in turn the food crisis as well,” she noted. “We need to understand that the [food supply crisis] has long roots. If we’re going to keep silent and be comfortable with our own privileges then we’re on the right track to a dystopian future.”

Whether Bakudapan succeeds in getting its message to a wider audience remains to be seen. What is certain is that “Hunger Tales” is worthy food for thought, not least for its participants.