Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

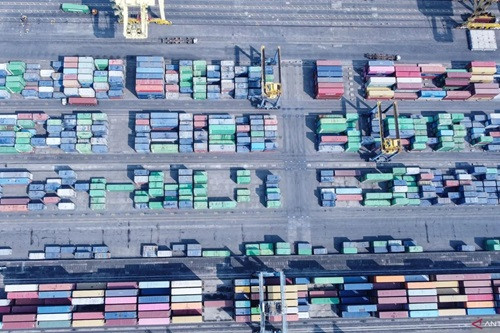

View all search resultsEmpty cargo ships drive up cost of maritime trade

The government's sea lane program needs to be complemented with an industrial development program targeting the eastern regions so they can manufacture goods to balance inbound-outbound logistics costs for shipments from western regions.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

D

omestic maritime trade remains costly despite the government’s subsidized sea lane, also known as the maritime highway, and even as the country’s eastern regions have gradually developed local production for trading with western regions.

The Transportation Ministry said that ships returning from eastern ports with empty cargo holds remained the core challenge of the sea lane program.

The ministry’s data showed that ships returning to their ports of origin carried roughly 30 percent of the cargo they had carried on their outward journey, due to low demand at destination ports. While the figure was double that of previous years, it was not enough to reduce shipping costs to the eastern regions, which would require each vessel to carry nearly the same amount in both inbound and outbound cargo.

Arif Toha Tjahjagama, the ministry’s sea transportation director general, blamed the logistics imbalance to undeveloped industries in regions along the sea lane. He added that Papua posed the greatest development challenge.

“There is not enough production as yet [in eastern regions] for transporting to the western [regions],” Arif told reporters, as the industries in many eastern regions were underdeveloped. He added that the ministry was gathering together many institutions to help solve the problem.

Read also: Unpacking the high costs of logistics

Despite the persisting challenges, Arif said the maritime highway program had lowered the prices of staple foods and other basic commodities between 20 and 40 percent.

The maritime highway has been in operation for almost eight years. The program was developed to solve domestic logistics issues in distributing staple foods and other finished goods between the country’s western and eastern regions, as more than 75 percent of Indonesian territory is comprised of marine space.

The maritime highway program subsidizes a large number of shipping lanes with a fleet made up of thousands of vessels operated by state-run companies as well as the Transportation Ministry. The ministry has recorded that the subsidy allocated for the program has continued to increase since it was inaugurated in 2015, reaching Rp 435 billion (US$29 million) in 2022 to accommodate more vessels and routes.

The government initially aimed to bring down logistics costs to 17 percent of GDP by 2024 from 23.5 percent in 2017. In comparison, logistics costs in Malaysia reached just 13 percent of GDP in 2017.

Andry Satrio Nugroho, who heads the Industry, Trade and Investment Center at the Institute for Development of Economics and Finance (Indef), said that many regions in eastern Indonesia lacked a competitive advantage compared to western regions. He added that insufficient human capital and infrastructure quality were among the many obstacles to growth, as the economy was still dependent on extractive resources.

Solving these issues was paramount, he said, if the government wanted to turn the eastern regions around from being a net consumer of goods produced in western regions.

Mapping regional potentials might not suffice, he added, as this should be followed with real efforts to develop those potentials.

Separately, Indonesian Logistics Association (ALI) chair Mahendra Rianto said that rather than insisting on using complicated container port and other shipping facilities, the government should use roll-on/roll-off (RORO) ships, which were designed to transport wheeled cargo like cars, trucks and other land vehicles and would cost less.

He said that the Philippines, also an archipelagic country, relied on thousands of RORO ships and had thus been able to bring down logistic costs to rural areas, so Indonesia could employ a similar strategy.

“We do not need anything too sophisticated, like forcing every port to have big cranes. This would make loading and unloading too costly, with large ports also incurring large expenses also,” said Mahendra.

“Why make many ports, whereas there are yet to be many [developed] industries in the eastern part of Indonesia?” he added.

Read also: Lack of return cargo from destination ports remains challenge for maritime highway

Maritime expert Saut Gurning from 10 November Institute of Technology said the government could target those regions that needed the subsidies the most, as private companies could operate some shipping routes.

“In reality, there are many regions that do not want to [lose] the subsidy, even though their figures, such as prices and logistic costs, have improved,” he said.