Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsJean Couteau's essential new volume describes the modern Balinese dilemma

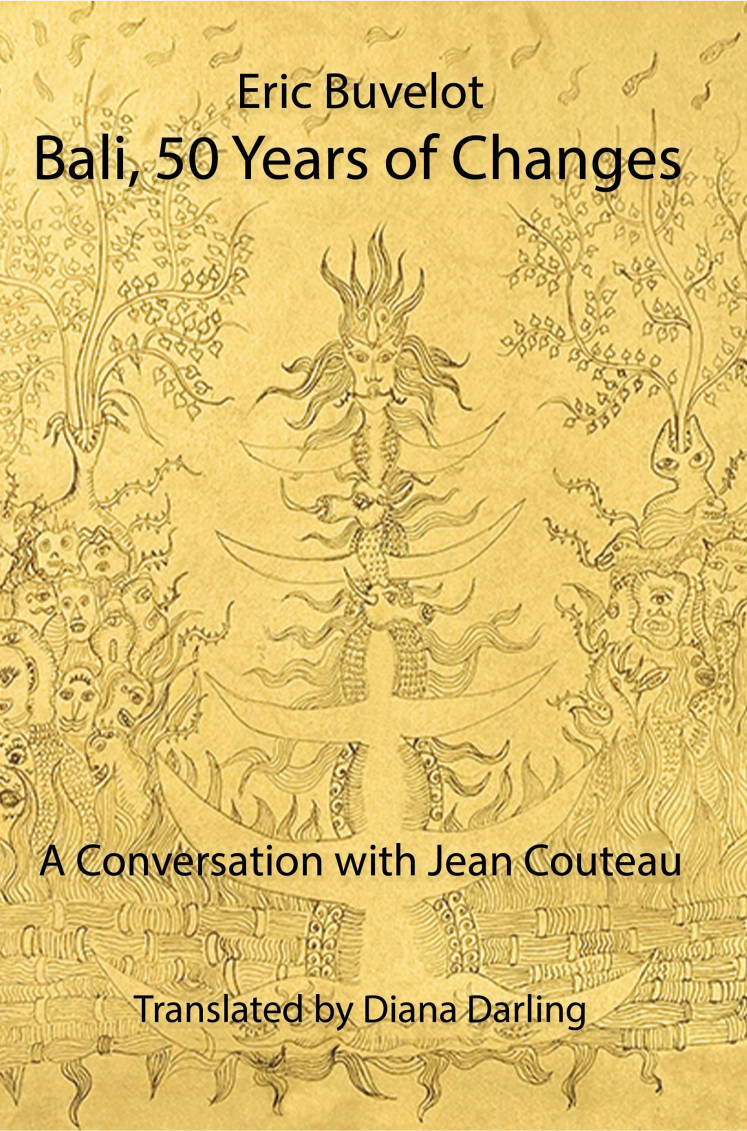

Bali, 50 Years of Changes: A Conversation with Jean Couteau by Eric Buvelot examines Bali's transformation – from a traditional agrarian to a capitalist service society. This enthralling exchange reveals complex and often paradoxical scenarios. The book is a quantum leap forward in comprehending modern Balinese.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

B

ali, 50 Years of Changes: A Conversation with Jean Couteau by Eric Buvelot examines Bali's transformation – from a traditional agrarian to a capitalist service society. This enthralling exchange reveals complex and often paradoxical scenarios. The book is a quantum leap forward in comprehending modern Balinese.

"During the past century, the world has invited itself to Bali, and in doing so, has broken the society's traditional balance," says Jean Couteau, a well-known multilingual writer (Indonesian, French, English), specialist of Bali and national columnist for Kompas newspaper.

Most of Bali's transformation has occurred since the 1970s when the island opened to tourism. In this book, an edited 270-page transcript of 20 hours of interviews granted to Buvelot over seven months, Couteau does not limit himself to statements. Instead, he delves into the multifaceted and often problematic dynamics that deeply impact Balinese culture and people's psyche.

"In the 1970s until the mid-1980s, there was a low level of urbanization; intellectual formation was based on religious symbolism rather than on strict religious tenets," Couteau said.

"[Tourism] was still ‘bringing something’ more than ‘taking something’, land had not yet become a commodity, and homogeneity in cultural life and behavior prevailed," Couteau adds. It was a change he had witnessed directly for over 40 years.

A lecturer at the Denpasar Institut Seni Indonesia (Indonesian Institute of the Arts) and graduate of the prestigious EHESS in Paris, Couteau's sphere of knowledge spans history, religion, politics, economics, nationalism, sexuality, women's rights, identity, the environment, invented traditions, ethnocentrism and more.

The book's dynamic to-and-fro, question-and-answer conversation engages from cover to cover. Buvelot's distinct ability to ask prying questions and intuitively respond to Couteau's insights enables the discussion to venture into ever deeper territory.

Heavy on information, the book aims at something other than being academic: it would be too rigid to retain the reader's attention. So Buvelot categorized his questions into four parts based on the principles of life in Hinduism: Kama, arta, darma and moksa. First published in France in 2021, it has been translated from French into English by noted author and Bali specialist Diana Darling.

The Balinese identity was traditionally defined by an inner perspective, looking toward the family, clan, village, temple and then the holy mountain Agung. It exclusively focused on Bali.

This has changed with the focus now on the outside world. There is a continuing shift toward Indonesian and international spaces. People now consider themselves Indonesian. Yet, at the same time, their identity is becoming increasingly focused on religion, evolving away from the traditional ancestors' cult toward international Hinduism. This phenomenon is accompanied by a shift from symbolism toward the absolutism of the truth.

This transformation may create problems.

"Bali has nothing to gain from taking refuge in either neotraditional or neo-Hindu hyper Balineseness," states Couteau, pointing out that correct practice, the emphasis on ritual, is being replaced by convention. Thus, aspects of ancestor worship, the core of the Balinese belief system, are attacked by sects wishing to introduce a more orthodox Hinduism.

"The master guru relationship is on the rise – a modern version of the old tradition of learning, not so much from the text but the affiliation to a new sect's master."

These points confirm seismic deviations from the past, tugging at the deeply enmeshed fabric of Balinese society.

Western perceptions of Bali as a paradise are wonderfully explained in Adrian Vicker's landmark Bali: A Paradise Created (first edition published in1989). Buvelot's conversation book with Couteau is an essential follow-up to Vicker's masterwork and a must-read for all those fascinated by Bali and concerned for its future. A selected bibliography and a list of relevant films add valuable material for those wishing to investigate further. Bali, 50 Years of Changes inspires one to learn more and to see the Balinese through a lens appropriate for the times.

"How should we decipher a situation two years ago of a man who killed his father with a keris during a trance ceremony?" asks Couteau.

"Most Balinese perceive it as the result of niskala forces at work. The one who died was destined to die because he had left the ‘field of pain’, the Balinese purgatory of his previous incarnation, before fully paying his debt. In cases like this, individual responsibility is not part of the interpretation. And events are concretely linked by karma across the incarnations."

Couteau notes that words relating to morality are mostly of foreign origin: The West will tend to create conceptual barriers, whereas, in Bali, there are none. "Traditionally, people see things differently as a balance between contradictory niskala forces."

Change is found across the board: In the 1970s, 4 percent of the population was non-Balinese; now, it is around 20 percent. Rapid socioeconomic growth shatters traditional stratification. Caste hierarchy is fading in the face of the order of diplomas and money.

"Yet, although the nouveau riches might question the validity of the caste Tri Wangsa system, they do not question the notion of status itself," notes Couteau. What matters is to stand out among the commoners. With urbanization and individual land ownership, the land is now recognized as a commodity encouraging a thriving new entrepreneurial model.

How will Bali appear in another 50 years? The Gods only know. Couteau suggests two means to counterbalance negative trends. The village, he says, must continue having the final word on just about everything. And a more universalist education system must be devised to counteract religious extremism.

Finally, this book must immediately be translated into Bahasa Indonesia to help foster a new era of self-reflection and discussion. It will initiate many other conversations that may open pathways to support the Balinese navigating the new millennium.