Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsExhibition marks Indonesian literary giant Chairil Anwar’s centennial

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

F

amed Indonesian poet Chairil Anwar continues to loom large in the country’s literary scene, as seen in a centennial exhibition at South Jakarta’s Salihara Arts Center, which celebrated his life and work.

“I’m but a wild animal

Exiled even from my own group

Even if bullets pierce my skin

I will still enrage and attack…

And I will care even less

I want to live a thousand more years!”

Chairil Anwar, Aku (I)

The poem’s message of defiance, individualism and rebellion continues to resonate today as when his poems were first published nearly 80 years ago in 1943, even as age rendered the writing on the brittle, discolored paper barely legible. Aku also set the tone for Indonesia’s independence struggle two years later. It earned Chairil the sobriquet of binatang jalang (wild animal), and cemented his preeminent place in Indonesian literature as part of the ’45 Generation. That generation headed the country’s artistic renaissance and inspired its struggle for independence from the Dutch.

A photo of the poet drawing on a cigarette while intensely gazing at the camera dwarfed the copy of Aku, affirming his reputation as a larger-than-life literary rebel. The picture’s effect is similar to Guerrillero Heroico (Heroic Guerrilla Fighter), Cuban photographer Alberto’s Korda’s 1960 photograph of Argentine-born revolutionary Che Guevara.

A labor of love

Aku and the iconography surrounding the poem make it the centerpiece of Aku Berkisar Antara Mereka (I Walk Among Them). Named after one of his poems, the exhibition by the Salihara Arts Center in cooperation with the H.B. Jassin Center of Literary Arts Documentation, which stores Chairil’s work, are among the events marking the centenary of Chairil’s birth on July 26, 1922, along with seminars and readings of his work.

Curators Laksmi Pamuntjak and Cecil Mariani noted that Aku Berkisar Antara Mereka, which began with Chairil’s birth in Medan to his premature death in Jakarta at the age of 26 in 1949. It aims to “reassess [Chairil’s] contribution to Indonesian literature and move beyond the binatang jalang myth”.

“A poet is a product of [the literary] traditions that precede him”, they noted in their curatorial, which mainly focused on his published works between his arrival in Jakarta in 1942 and his death. His multilingual mastery of Dutch, German and English, as well as Indonesian, perhaps enabled Chairil to raise “the Indonesian language’s potential by uncovering new and old elements at the local and international levels. He also brought [Indonesian] poetry down to earth, namely in its sounds and lyricism, and in doing so invented new words and structure [for the Indonesian language]”.

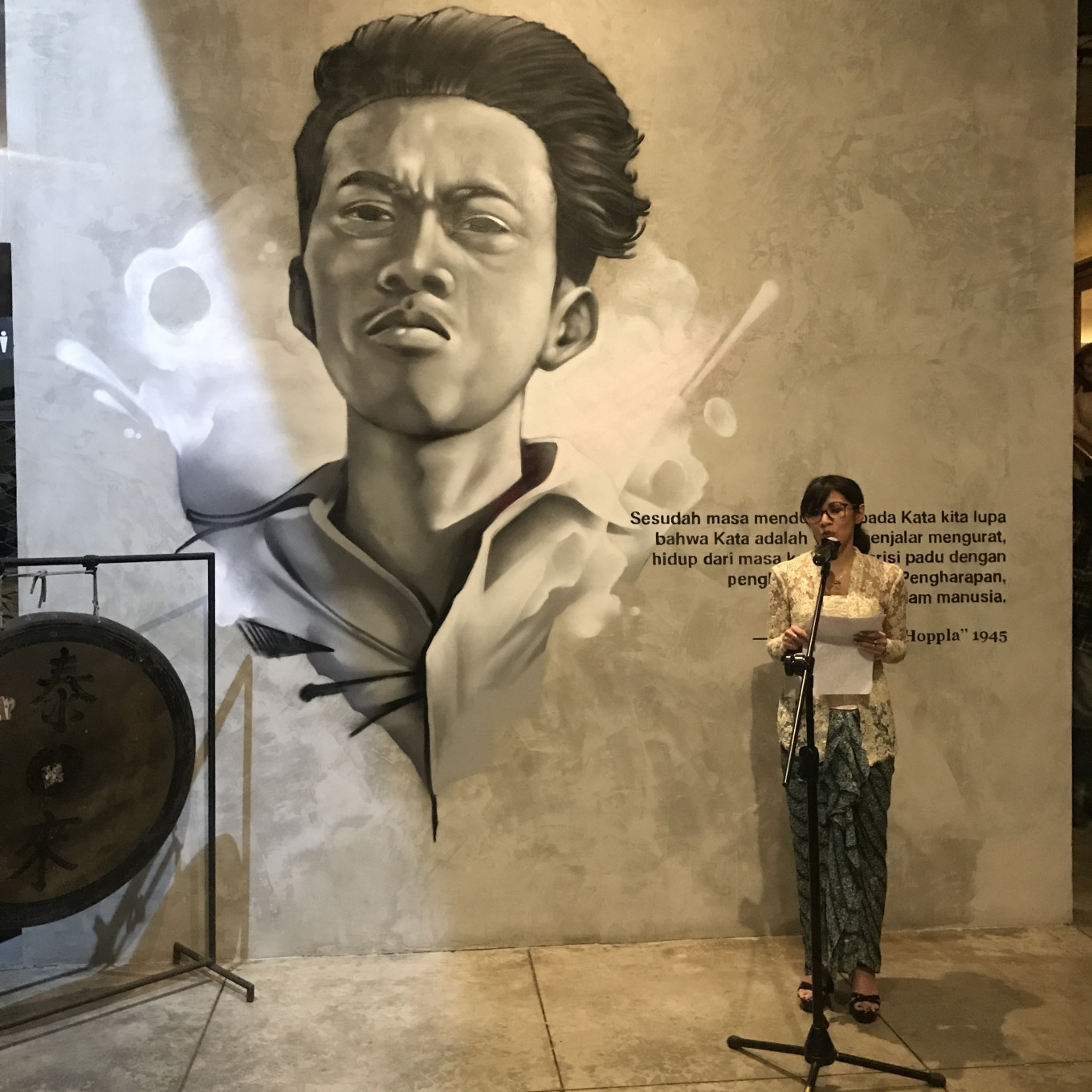

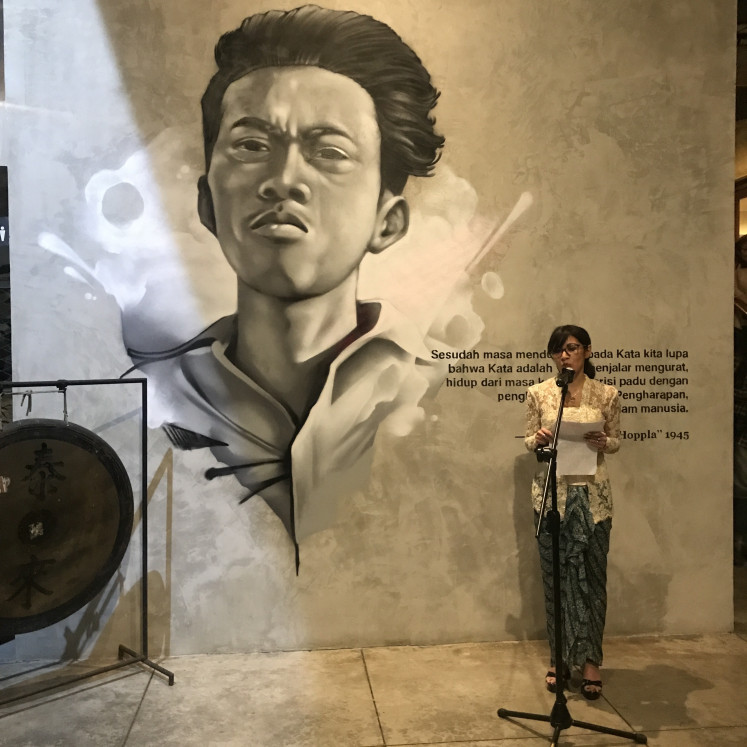

In her opening remarks, Laksmi added that the exhibition is held on Oct. 28 to coincide with the Youth Pledge (Sumpah Pemuda) by young Indonesian nationalists in 1928 to have “one motherland, one nation and one language for the country”.

“For me, [Aku Berkisar Antara Mereka] was a labor of love, as Chairil’s poems have an evocative, magical quality. Working on the exhibition allowed me to rediscover and relearn his work, and in doing so, I found much about him that I did not know,” said the writer of the best-selling novels Amba and Aruna dan Lidahnya (Aruna and Her Palate).

“Chairil’s works transcend his era, as they continued to influence how we read and write poetry. They include Goenawan Mohammad, Nirwan Dewanto and Sapardi Djoko Damono, as well as other contemporary writers.”

Interspersed with passages from Chairil’s work were his relations with fellow writers, among them Asrul Sani and Rivai Apin, with whom he founded the Gelanggang Seniman Merdeka (Free Artists Arena). Like Chairil, the former is a multilingual essayist, screenwriter and violinist who mastered English, Dutch and German. On the other hand, Rivai paid tribute to Chairil through his work “Orang Penghabisan” (Man at the Finish) and his reflections on Chairil and his death.

More vital to the exhibition was his relations with literary critic H.B. Jassin, whom Chairil called “his savior from the skies”.

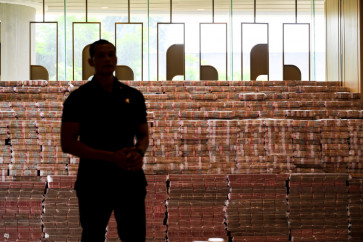

“Jassin’s admiration for [Chairil] inspired him to make a compilation of his work, a ‘treasure trove’ that eventually became the H.B. Jassin Center of Literary Arts Documentation, which he founded in 1976.”

Chairil also entrusted Jassin with his private matters, including sending money to his widowed mother.

Getting to know the writer: Visitors view an original copy of 'Aku' and an iconic photograph of Chairil Anwar. (JP/Tunggul Wirajuda) (JP/Tunggul Wirajuda)The man behind the myth

The exhibition portrayed Chairil and the eclectic world around him, including his interaction with Indonesian painters Affandi and S. Sudjojono. Yet the gregarious poet’s social circles “transcend [social] classes, professions and generations and were not confined to literati and artists, or men and women. They also include politicians and prostitutes, independence fighters and becak drivers”.

Laksmi noted that their diversity perhaps influenced his views and work, accurate to a stanza in Aku Berkisar Antara Mereka, which observed that “I walk among them, forcing me/ to change my looks at the edge of the road, making me [see the world] through their eyes.”

Among them are poems about two women called “Tuti Artic” and Sri Ajati. As enigmatic characters not unlike the “Dark Lady” of Shakespeare’s sonnets, he warned of the former that “love is a danger that runs the risk of fading away”, while the second poem chronicled Chairil’s unrequited love for the latter.

Chairil derived much of his inspiration from foreign writers such as T.S. Eliot, John Steinbeck and Ernest Hemingway, many of whose works he translated into Indonesian. This part of his legacy is also the most contentious, as the Mimbar Indonesia newspaper and other publications accused him of plagiarizing their work.

“One poem by Chairil that is widely thought to be plagiarism is Datang Dara, Hilang Dara [A Girl Comes, A Girl Goes], which in turn was based on [Chinese writer] Hsu Chih-Mo’ work, A Song of the Sea. Chairil insisted that the poem was an adaptation, though H.B. Jassin and other institutions agreed that the work was plagiarism,” said the curators.

“However, Jassin and writer Sutan Takdir Alisyahbana agreed that Karawang-Bekasi, a Chairil poem influenced by American poet Archibald MacLeish’s work The Dead Soldiers, was inspired by the latter work, not plagiarizing from it.”

While Laksmi acknowledged that the debate on which of Chairil’s works are original, inspired by others, or translated as well as plagiarized from continues, she maintained that it does not define Aku Berkisar Antara Mereka.

“I try to look at Chairil’s legacy, including his plagiarism, in a balanced manner, especially in his centennial exhibition. We need to balance an artist’s merits and flaws, whether those who plagiarize their work like Chairil, or tap into their chauvinistic, paternalistic and exploitative impulses like Picasso.” She added that Chairil adds depth and richness to his works, whether he derived them from other sources or was inspired by his surroundings.

Laksmi hoped that the exhibition would raise awareness and interest in Chairil’s life and works among aspiring and experienced writers and the public at large.

Aku Berkisar Antara Mereka

Open Tuesday to Sunday, 11 a.m. – 7 p.m., closed on Mondays

To Dec. 4

Galeri Salihara

Tickets: Rp. 35,000 per person, ages seven and up

Jl. Salihara 16, South Jakarta 12520

Website: salihara.org

Email: media@salihara.org

Instagram @komunitas_salihara

Twitter @salihara