Biodiversity, climate: ASEAN’s next challenges

Indonesia's 2023 ASEAN chairmanship presents an opportunity to tweak the bloc's institutional structure to mainstream policies and actions on biodiversity preservation and climate change across all three ASEAN communities

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

I

f there was a ranking of the most effective ASEAN institutions, the ASEAN Centre for Biodiversity (ACB) would probably top the chart.

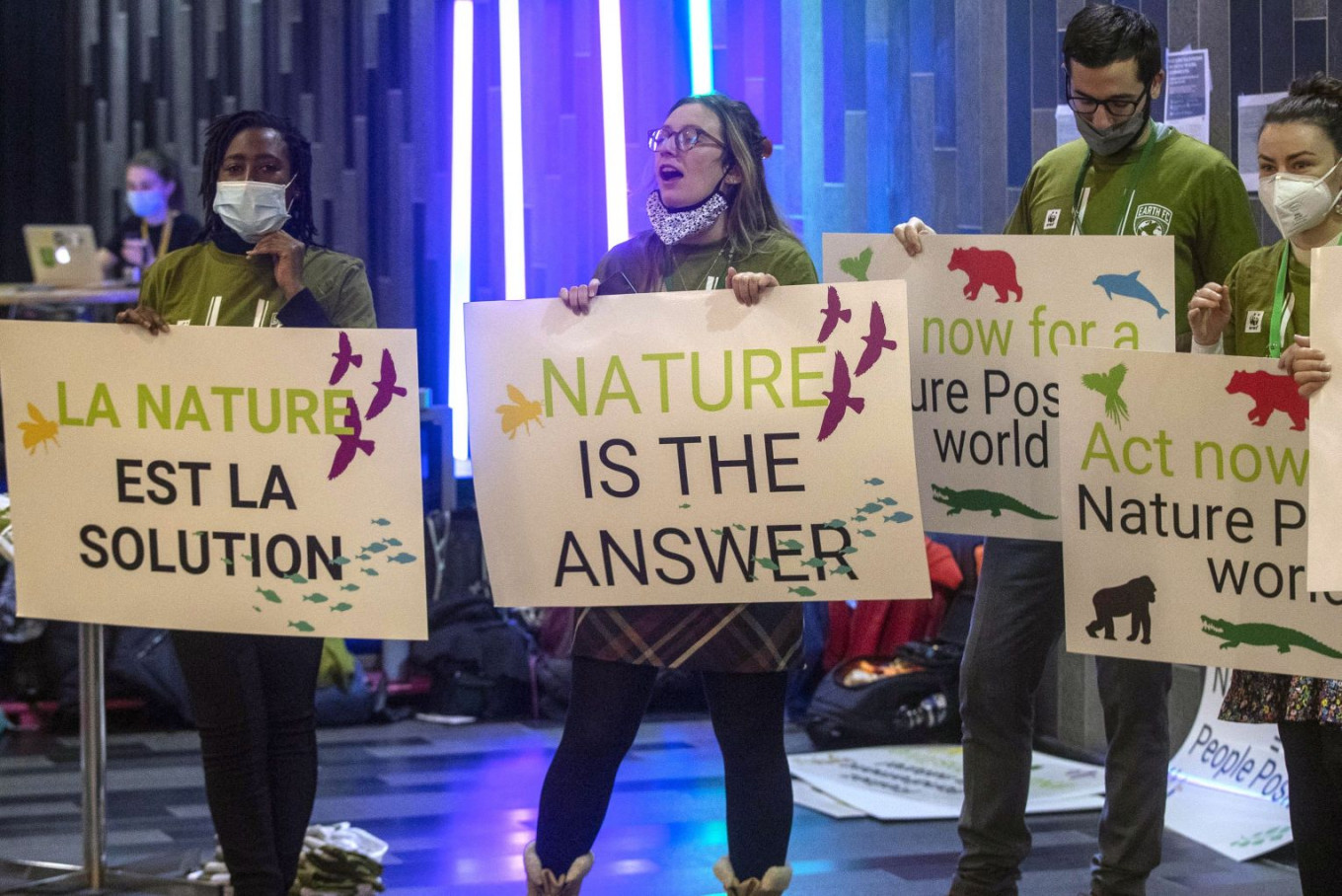

After the agreement earlier this month in Montreal on the new Global Biodiversity Framework to replace the Aichi Framework, a very important document that was neglected and overlooked by the global community, we have another chance at saving and protecting our planet.

ASEAN member states can take the lead on this if they truly work as a team with a better structured Secretariat and some bottom-up innovations.

The COP15 Convention on Biological Diversity chaired by China, which was held in two parts with part 1 held in October 2021 in Kunming, China, and part 2 on Dec. 7-19, 2022 in Montreal, Canada, finally received due attention.

ASEAN issued two statements about the convention over the past two years, with the most recent one, a joint declaration issued by the bloc’s Cambodian chair on behalf of all members, issued on Dec. 12. Though devoid of clear commitments and targets, at least ASEAN showed its face at the negotiating table, a positive sign that augurs well for the future.

The ACB is the result of a successful partnership between ASEAN and the European Union and should become more and more central in this perspective, as it has the potential to become one of the world’s most respected research and advocacy centers on matters related to biodiversity.

But the challenges ahead for ACB are not only about gathering more resources, even if more resources would be instrumental to building the body of research it has produced so far, such as the ASEAN Biodiversity Outlook.

ASEAN also needs stronger political commitment and more agile governance to keep pace with the level of ambition required to deal with biodiversity preservation and climate change.

For example, the ASEAN Ministerial Meeting on the Environment (AMME) meets only once every two years, like most of the bloc’s ministerial meetings. The 16th AMME was held in Jakarta in October 2021, and the next AMME will be held in Laos in 2023.

Compare this to the Conference of the Parties to the ASEAN Agreement on Transboundary Haze Pollution, over which the member states meet annually, with the last meeting held in Singapore on Oct. 20, 2022.

This has happened, perhaps, because the ASEAN states attach considerable relevance to an issue like haze pollution that affects millions of people across Southeast Asia.

Considering that the AMME is normally held in conjunction with the transboundary haze conference, was it so unimaginable to hold an AMME this October in Singapore, even if informally?

Answering this question is akin to solving some of the most intrinsic secrets of ASEAN, but we can simply guess that there is a lot of complacency and comfort in running things as they always have, and this is obviously unfortunate and ill timed.

While we cannot expect magic from Indonesia’s upcoming ASEAN chairmanship, perhaps President Joko “Jokowi” Widodo could try to venture a bit outside the playbook on the bloc’s governance and bring in some new arrangements, like holding annual (or even biannual) ministerial meetings for all policy areas. Even if some of these are held informally, like the EU’s many ministerial meetings, ASEAN still needs to hold political meetings involving its leaders and ministers more frequently.

And in Southeast Asia, we could not have a fuller plate on matters of biodiversity and climate change: two areas that, despite the global distortion of UN arrangements governing these two issues, are intrinsically linked and should be treated as such.

For example, ASEAN is advancing on the circular economy, a task that, to some extent, is also being carried forward by the ASEAN Centre for Sustainable Development Studies and Dialogue (ACSDSD) at Mahidol University in Bangkok. There is no doubt that this center should not travel on a track parallel to that of the ACB.

Rather, the “journeys” of these two institutions, which are certainly different in scope, nature and scale, should somehow come closer to each other and be aligned.

The same could be said for the upcoming ASEAN Centre for Climate Change, an idea launched by Brunei that is taking shape by the day.

We really need to work on building a team through the “network” approach, in which one of the deputy secretaries-general at the ASEAN Secretariat ensures coherence, coordination and a unified approach.

Moreover, the environment is not prominent in the archaic institutional setup of the ASEAN Secretariat in Jakarta. Only one division under the Sustainable Development Directorate, which falls under the ASEAN Socio-Cultural Community (ASCC), deals with it.

Could Indonesia’s 2023 ASEAN chairmanship come up with a different setup in which environmental issues, including biodiversity and climate change, are given stronger prominence? Perhaps we should even envision a whole new department that is exclusively dedicated to these issues to actually mainstream them across the three communities (Political-Security, Economic, Socio-Cultural) that form the structure of ASEAN. It could also be a nimble structure that would ensure that all departments and directorates within the Secretariat truly embed green policies.

In addition, ASEAN is also making strides in promoting new guidelines on sustainable agriculture that is key to preserving biodiversity and reducing harmful haze pollution.

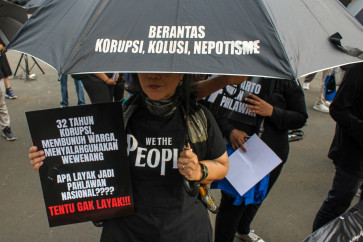

Let’s not forget that, ultimately, it is not about just ensuring a faster, more responsive system of regional governance, but also about including and bringing people closer to the decision-making process.

Indonesia has been a trailblazer in localizing the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), and there could not be a better way to promote biodiversity and climate action regionally than by involving and engaging the citizens of Southeast Asia more.

What about having the 2023 ASEAN chair promote citizens’ assemblies on biodiversity and climate change in both urban and rural settings?

Leveraging on its tradition of discussion and deliberation, Indonesia could jolt the idea that policymaking is an exercise that excludes people. For example, while strengthening or building new nature-oriented institutions, why not be inspired by the working approach and philosophy of Centre for Environment and Development Studies (CEMUS) at Sweden’s Uppsala University?

CEMUS is a student-centered and student-led institution that thrives on collaborations and partnerships.

Working more closely with UN-ESCAP, already the regional champion in promoting sustainable development, could be another key to pushing the issues in an inclusive, bottom-up way.

Certainly, we need more events for discussion and debate.

While we wait for more AMMEs, the ASEAN Ministerial Dialogue on Accelerating Actions to Achieve the SDGs is an interesting platform, if it is leveraged. And it could be the venue where the ACB, the ASCC and the upcoming climate center present a united front.

Something that was perhaps overlooked in the final declaration of the ASEAN Leaders’ Summit in Phnom Penh in November is the idea of an ASEAN Green Deal.

Exploring it and enabling people to express their views on it could be one of the most exciting tasks of Indonesia’s ASEAN chairmanship in 2023.

***

The writer comments on social inclusion, youth development, regional integration, SDGs and human rights in the context of the Asia-Pacific.