Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPoor planning causes PLN to pay more for Batang Toru hydropower plant

The Batang Toru hydropower plant project sounds like a good plan, but deep down it is plagued with poor oversight and a lack of transparency that may hurt PLN.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

T

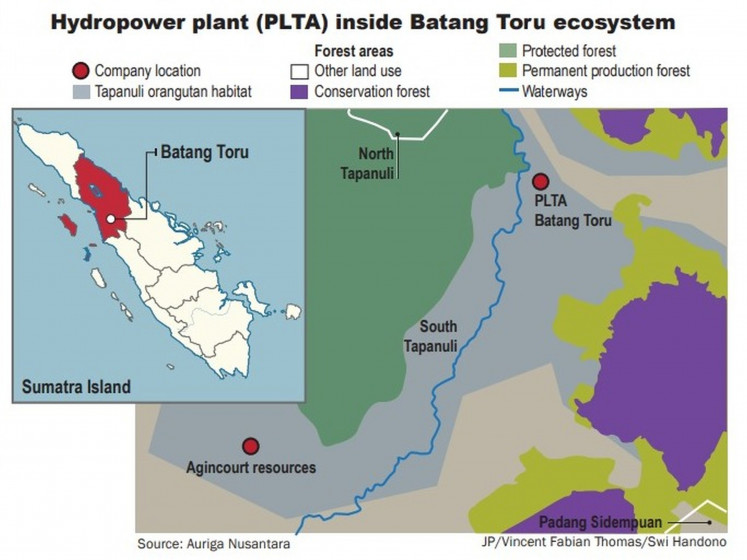

he construction of a hydropower plant in Batang Toru district in South Tapanuli has been causing a global controversy for years as it was built in the habitat of the endangered Tapanuli orangutans. The Jakarta Post joined the Society of Indonesian Environmental Journalists (SIEJ) in collaborative reporting to visit the construction site and nearby villages in December 2022 to get the latest on the development of the project. This is the first part of the report.

On the surface, the Batang Toru hydropower plant project sounds like a good plan. Designed as a peaking power plant, also known as a peaker, for North Sumatra, the 510-megawatt grid will be powered by a water dam, which is aimed to increase the country’s renewable energy capacity.

But poor oversight and lack of transparency surrounding the project left the project in limbo, about six years after the project development had kicked off. Global protests over the encroachment into the Tapanuli orangutan (Pongo tapanuliensis) habitat led the project into financial shambles and an uncertain future.

State-owned electricity monopoly PT PLN is Indonesia’s major force behind the international project, owning 25 percent of PT North Sumatra Hydro Energy (NSHE), a joint-venture company tasked with development and operation of the project. PLN participated through its wholly owned subsidiary PT Pembangkitan Jawa Bali Investasi (PJBI).

Under PLN’s direction, the Chinese government’s state-owned State Development and Investment Corporation (SDIC) subsidiary, SDIC Power, owns around 70 percent of the NSHE’s stake, making it a China-owned project. It is also classified as China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

The hydropower project was initially set to be completed in 2022 but has been delayed until 2026 as the project faced many setbacks over the course of its construction.

The major constraint came from worldwide protests over its threat to the habitat of the Tapanuli orangutan, which the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) declared critically endangered in 2017, the year when most of the project development began.

A study by Riverscope in 2021 estimated the delay may extend to 2034, making the project even more costly given controversies at hand.

Hydropower plant (PLTA) inside Batang Toru ecosystem. (Auriga Nusantara/JP/Vincent Fabian Thomas/Swi Handono)

No documents, no explanations

An audit report on the country’s independent-power producers by the Supreme Audit Agency (BPK) in 2020 pointed out some of the irregularities in the project.

The power plant is projected to cost US$1.68 billion, 75 percent of which is planned to be financed by loans and the rest to be covered by equity injected by its shareholders, including PLN and SDIC Power.

Since PLN held a quarter of NSHE’s shares, the BPK report revealed that it was required to inject at least $104.2 million of capital to finance the project development. The amount of capital injection soared 21 percent above what had first been calculated back in 2014, when the company had only been required to pay $86.8 million.

The BPK also found that PLN could not show documents or explain the reasons behind the swelling project costs, which happened in 2017 when the project construction began.

As of 2020, PLN had injected $76.3 million, or about 73 percent of its funding commitment, into the project. BPK auditors deemed the amount as “over-injected” due to slow progress of the development. They reported that as of October 2020, the project was only around 11-percent complete, far from the target of 78.98 percent.

When BPK auditors asked PLN to provide documents to elaborate the spending on the capital injection in NSHE and prove its accountability, the firm also could not show any.

PLN did not respond to The Jakarta Post’s queries on this matter sent on Jan. 18.

Furthermore, BPK auditors found PLN entered the project through its subsidiary without acquiring any approval from a shareholder meeting nor holding an internal discussion among its board of directors, a violation of PLN's own statute.

Other supporting documents, regarding business feasibility, technical capability and financial evaluation as well as calculations on the projected future benefit or profit of the project, among many others, were not shown by PLN to the auditors.

Based on those findings, the BPK ruled that PLN had violated the State-Owned Enterprises (SOEs) ministerial regulation 1/2011 on good governance and its own statute.

This undated photo shows an aerial view of a tunnel dug by PT North Sumatra Hydro Energy (NSHE) in Marancar district, South Tapanuli, North Sumatra. (Sinohydro/PR Team)

Signs of corruption?

Egi Primayogha from graft-watchdog Indonesia Corruption Watch (ICW) urged the government and law-enforcement institutions to take action on irregularities found in the BPK audit report.

“When oversight is lacking, or entirely absent, it opens the door to corrupt practices and graft,” Egi told the Post on Feb. 8.

Egi said it was plausible that PLN’s lack of accountability may also incur a financial loss to the state, which law enforcement institutions could look into based on the Corruption Law.

The BPK report revealed PLN appointed NSHE directly as developer of Batang Toru power plant, which in 2015 was owned by Jakarta-based PT Dharma Hydro Nusantara (DHN) and Singapore-based Fareast Green Energy (FEGE), neither of which had any experience in building a dam.

“A direct appointment for unreputable firms does not always mean there is graft. But it does not rule out the possibility. A majority of convicted graft cases involve this scheme,” Egi said.

The agreement between NSHE and PLN was inked when Sofyan Basir sat as PLN CEO. The Corruption Eradication Commission (KPK) named him a suspect in a corruption case in the coal-fired power plant Riau-1 in 2019. He stood trial but the court did not find him guilty and later acquitted him.

Responding to the Post in an email on Jan. 31, PLN spokesperson Gregorius Adi Trianto said the company had abided by the regulations and their direct appointment to NSHE had been approved by the Energy and Mineral Resources Ministry (ESDM) in 2013.

NSHE did not respond to an interview request or inquiries sent to the company.

‘Expensive’ design

Experts also criticized PLN for designing the power plant as a peaker, which is more expensive to build than a regular, also known as a baseload, hydropower plant. A peaker is usually run only during the highest point of demand in a day, unlike baseloads that can operate 24/7.

Due to its nature of only operating during high demand, the electricity produced by a peaker is priced at 12.8 US cents per kilowatt hour, according to the BPK audit report, whereas experts said a baseload hydropower plant produced electricity at a price between 3 and 4 US cents per KWh.

The price of electricity that PLN agreed to pay for the Batang Toru plant is also far more expensive compared with other hydropower peakers. As comparisons, the electricity from Poso hydropower plant in Central Sulawesi, which has the capacity of 515 MW, is priced at 7.4 US cents per KWh, while another in Merangin, Jambi, with 350 MW in capacity, is priced at 10.7 US cents per KWh, according to the BPK audit report.

The major criticism of PLN’s decision to build a peaker stems from the fact that electricity supply in Sumatra far exceeded demand available throughout the island, meaning a large number of megawatts produced by power plants on the island are currently left unused and dissipated.

In 2022, PLN’s electricity procurement plan (RUPTL) estimated Sumatra produces 48,633 gigawatt hours of electricity, from which it experiences an excess supply of 7,292 GWh. The excess supply is expected to soar to 10,000 GWh in the next decade.

“What we should be concerned about is not when this hydropower plant will finally be completed, but that demand does not rise as much as expected. Then PLN must purchase electricity, albeit unused,” Elrika Hamdi, an energy analyst at the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA) said on Jan. 13.

In line with Elrika’s concerns, PLN slashed average annual demand projection on Sumatra to just 6.56 percent in the latest RUPTL from 7.9 percent previously.

Elrika presumes the designers of the project must have taken into account North Sumatra’s conditions at least a decade ago, when the province was deprived of electricity.

However, it failed to take into account that interconnections were now built between northern and southern Sumatra, which allowed a more-flexible transfer of electricity produced between each region, Elrika said, concluding that a peaker hydropower plant might not be needed now.

Future burden for PLN

Dwi Sawung, an energy campaigner at environmental-group Wahana Lingkungan Indonesia (Walhi), said the agreement between PLN and NSHE would ensure the developer would get paid despite the electricity not being used. As sole off-taker of the electricity, PLN would definitely be the one taking the financial burden.

“The agreement will make PLN losses [in this project] inevitable,” he said.

Elrika said developers of the project could consider altering the design so it could serve as a much-needed replacement for baseload coal-power plants that the government was planning to phase out, rather than continuing the project as a peaker.

However, it would have its own challenges, she said, adding that the change in design would be a major one, since a peaker and a baseload had completely different complexities.

Walhi’s Sawung added if the change had taken place, the electricity capacity would be far lower than 510 MW given the nature of the Batang Toru River that did not produce as much current as other rivers supporting other hydropower sites in Indonesia.

“This would make the project less bankable and difficult to acquire financing due to its smaller scale,” Sawung said.

With PLN holding a quarter of the total shares, it would then have to provide additional funds for a future injection if there was a cost overrun to avoid dilution on its shares.

“Whenever there is a cost overrun, then it is usually the responsibility of the shareholders,” IEEFA’s Elrika said.

She added that more capital would be locked in the delayed project, costing the firm opportunities to invest in more-profitable and urgent projects.

PLN’s Gregorius said the company had been aware the Sumatra electricity system was interconnected. He said the company would raise electricity demand by targeting the agriculture sector and other companies in the region so they would no longer generate electricity by their own plants.

“Batang Toru dam will be operated as a peaking plant to reduce and replace the role of gas and diesel power plants [currently operated by the companies] with much competitive cost,” he said.