Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsThe unsolved problems of our construction of knowledge

The increasing role of the middle class in the current trend of religious revival shows that, while the socio-economic gap has been widened, the fluidity of religious sentiment has become the social glue that sticks people from various socio-economic backgrounds together.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

I

t was not the first time that Gita Savitri, a prominent Instagram celebrity and author, became a source of debate on social media. Earlier this year, she inspired controversy regarding her choice to be child-free. Last year, she had to confront public hostility for a similar reason.

When the public discusses divisive issues such as human rights, freedom of expression and the lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) community, we are often trapped in the dichotomy between the open-minded and closed-minded. Yet, what is absent from the polemic is an understanding of the construction of knowledge that systematically affects the dichotomy.

We can trace the difference between open-minded and closed-minded groups from the division between two major academic subjects in Indonesian universities: science and technology and social science and humanities. Historically speaking, the division follows the Western-based construction of knowledge, particularly as Indonesian universities were established as a colonial legacy.

However, to differentiate our universities from Western institutions, the New Order regime aimed to combine science and technology (ilmu pengetahuan dan teknologi, Iptek) and faith and piety (iman dan taqwa, Imtaq). The proponent of Iptek and Imtaq was BJ Habibie, the country’s third president, who gained his educational and professional credentials from Western institutions and had a strong religious commitment at the same time.

Furthermore, the outcomes of science and technology were more practical in supporting the goals of national development, particularly through physical infrastructure and economic development. Obviously, as a developing country, Indonesia needs more applicable knowledge that has been central to technical and engineering subjects in top Indonesian universities.

In contrast, the nature of social science and humanities has always been less practical and more critical toward the establishment of Indonesia as a modern nation. Consequently, the government has not been interested in promoting the academic fields for national development.

The tendency has had a significant consequence. While our scientists and engineers are increasingly religious and political, our social scientists and humanists are increasingly secular and skeptical.

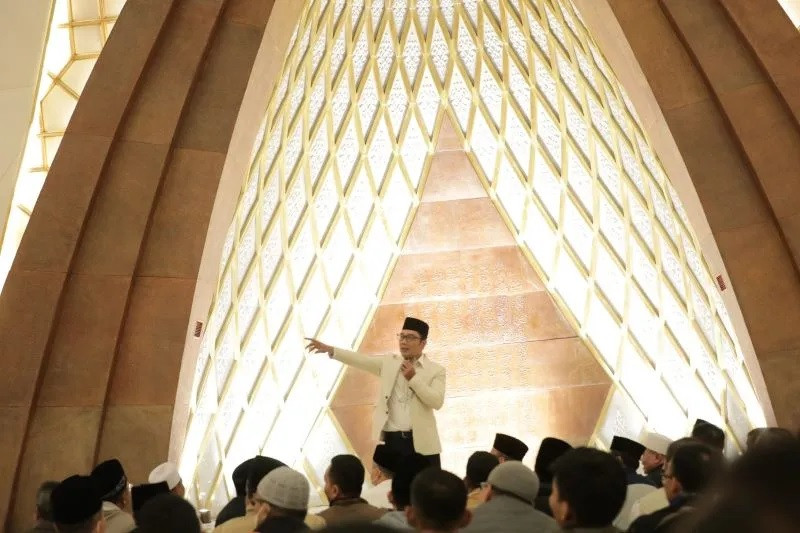

Obviously, in the current climate of religious revival, the religious and political will gain more popularity than the secular and skeptical. For instance, the decision of West Java Governor Ridwan Kamil, better known as Emil, to build the Grand Mosque of West Java (Masjid Agung Al-Jabbar) led to two different public perceptions. Aside from being governor, Emil, is also an architect and a graduate of the prestigious Bandung Institute of Technology and the University of California, Berkeley, the United States.

His choice of building an iconic mosque, rather than much-needed secular infrastructure such as public transportation, shows the strength of religious sentiment against the secular understanding. The polarity between the two phenomena has been clear: While Emil is increasingly popular due to his religious sentiment, Gita is becoming more alienated due to her support for secular causes such as human rights, freedom of expression and the LGBT community.

We also need to emphasize the fact that our top universities, as the beacons of the construction of knowledge, are also problematic. The latest report by Kompas, for instance, reveals the systematic fraudulent practices in producing academic publications that challenge the intellectual integrity of Indonesian universities. It is also common knowledge that, while aiming to become world-class institutions, our research infrastructure is underfunded and undervalued, hindering the capacity of our researchers to become world-class scholars.

Herein lies the problem of the construction of knowledge in contemporary Indonesia. Inside universities, the production and circulation of knowledge in all fields is fraudulent, undervalued and underfunded. Outside universities, the quality of the knowledge is still far from world-class yet inaccessible to the lay public at the same time.

It is not surprising that people on Twitter often dub the academic work of our researchers as fafifu wasweswos, a disparaging expression signaling the insignificance and inaccessibility of academic work for the lay public in this developing country.

At the same time, due to the abovementioned ambition to integrate Iptek and Imtaq, we can see how religious sentiment could easily penetrate our secular universities. It is common, and even compulsory, for our secular universities to have their grand mosque with routine religious training inside.

To some extent, the current trend of religious revival is well supported by the decades of growing religious sentiment among the well-educated population in the sought-after subjects of secular universities, such as engineering and information technology.

Outside universities, religious knowledge is also highly democratic and accessible to the lay public. Anyone, from any background and walk of life, can attend religious sermons in a more accessible space than our secular universities.

The increasing role of the middle class in the current trend of religious revival shows that, while the socio-economic gap has been widened, the fluidity of religious sentiment has become the social glue that sticks people from various socio-economic backgrounds together.

In contrast, it is increasingly difficult for secular knowledge in social science and humanities to permeate outside universities. The jargon, controversies and Western-influenced secular knowledge are increasingly elitist and fundamentally inaccessible to the Indonesian public, which is increasingly more religious. At the same time, to study social science and humanities subjects in top universities, many of which are deemed not sought-after in the job market, aspiring students still need to pass a highly competitive entrance exam and pay unaffordable tuition fees.

For government and policymakers, our construction of knowledge should become a critical consideration in various human development programs. For instance, the current debate about LPDP government scholarship awardees still focuses on their obligation to return to Indonesia soon after finishing their studies overseas. Instead, we also need to think that when sending our promising scholars to top Western universities, who are their role models? Do we aspire to them to become Gita, Emil or Habibie?

Furthermore, as the 2024 elections approach, and with religious sentiment becoming a major political commodity, we need more secular knowledge that is relevant, accessible and contextual. Otherwise, we need to rethink who is open-minded and who is close-minded in our intellectual and political battlefield.

***

The writer is a lecturer at the Communication Department, Bina Nusantara University, Jakarta, with a PhD in media and communication from the Centre for Cultural and Media Policy Studies, University of Warwick, the United Kingdom.