Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsFor Asian history in Australia, check out Broome

These days, the town of Broome is home to a population of mixed European, indigenous and Asian heritage. It is also frequented by indigenous people making journeys from their homelands

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

F

requented by tourists for its beaches, camel-rides and abundant 4-wheel-driving possibilities, Broome may seem a world away from Western Australia’s cosmopolitan capital of Perth, but scratch just a bit beneath the surface and it’s easy to see signs of this faraway coastal town’s multicultural history.

A sudden glare and warm, slightly humid air greets passengers disembarking the plane. As they take the short walk across the tarmac into the country house-like building that is Broome’s international airport, it becomes clear that even in peak season, Broome is not the type of tourist hub that brims with action and flashing lights.

Instead, the colours of the dirt — in so many shades of reds and browns — and the vast blue sky blending into the turquoise and navy hues of the ocean suggest a slower pace of life and an invitation to further explore the expanses of the rugged outback known as the Kimberley.

Located more than 2,200 km north of Perth, but only 870 km south of Kupang, East Nusa Tenggara, Broome is Western Australia’s answer to a segment of Australia’s domestic tourist market whose idea of the perfect “tropical holiday” is sun, sea and the freedom to roam, minus the hassle of passing through immigration and overcoming language and cultural barriers.

Water games: Kimberly's red earth can be clearly seen by kayakers paddling around Gantheaume Point's rocky outcrop. (JP/Prapti Widinugraheni)At peak tourist season, which coincides with the winter school holidays and the Kimberley region’s dry season, holiday-makers regularly expand Broome’s urban population threefold from the 14,776 recorded by the Australian Bureau of Statistics last year.

It is during these peak periods that Broome’s local entrepreneurs make a killing — pearl jewellery shop-owners, camel-ride operators and businesses selling 4-wheel-drive excursions, helicopter rides and chartered seaplane adventures — as they capitalise on natural landmarks such as Cable Beach, Roebuck Bay and the ancient rocky outcrops at Gantheaume Point.

But a 10-minute walk around town is all it takes to appreciate Broome as more than just a backwater that comes to life a couple of times a year.

Broome’s heart lies in its town center and, like the splendid boabs that adorn its streets, it is where Broome’s historical roots are firmly planted.

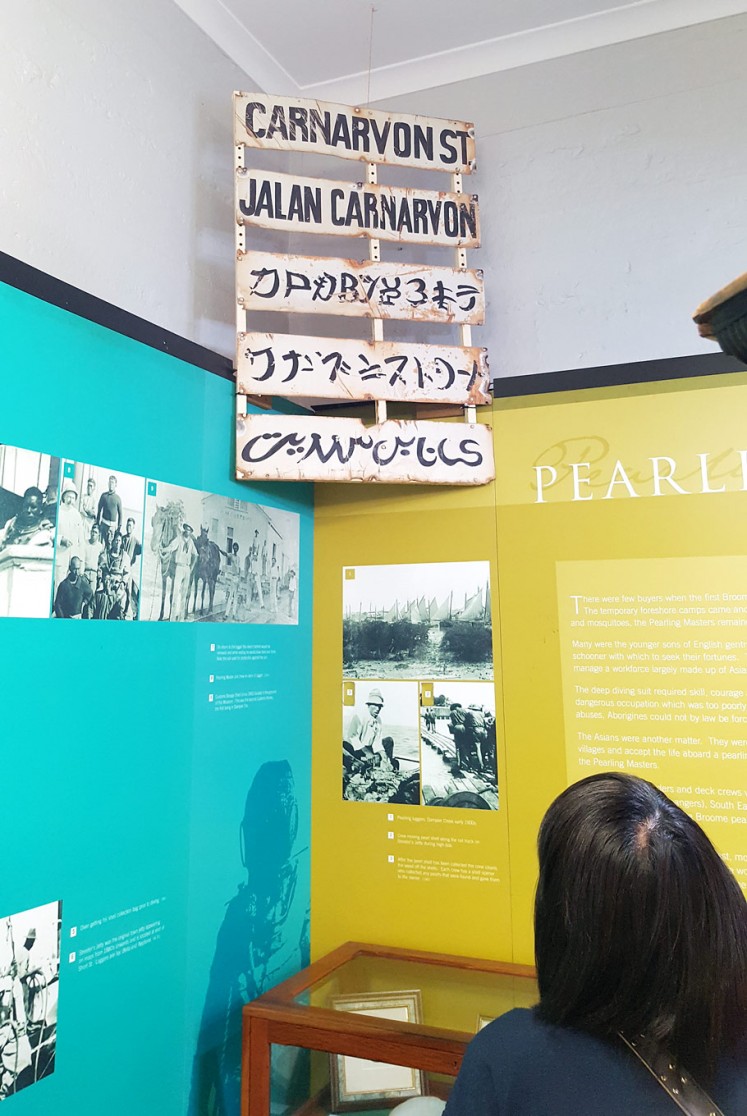

Places called “Johnny Chi Lane,” “Sam Su Lane,” “Manado Court” and “Chinatown,” red-painted wooden archways, street signage written in typeface suggesting Japanese or Chinese calligraphy, a museum artefact in the form of a street sign for “Jalan Carnarvon” written in five languages, and bronze life-size statues of non-Caucasian historical figures, are not landmarks one would expect to find in an outback Australian town. But Broome never started out as a typical outback Australian town.

Known today as a tourist destination, Broome’s original claim to fame involved pearls and pearling. For thousands of years, Broome’s Yawuru people and neighbouring groups used pearl shells for ceremonial and exchange purposes. It wasn’t until the 1860s that Europeans exploring the continent’s northwest coast noticed the excellent quality of the pearl shells used by the First Peoples.

This encounter changed the face of Broome forever: in their desperation for pearl shells — used in Europe as buttons, inlays and ornaments — the Europeans soon engaged in the practice of enslaving, or “blackbirding”, Aboriginal “skindivers,” forcing them to collect pearl shells from seabeds at depths of up to 12 meters.

Blackbirding continued for several decades until eventually shell stocks in shallow waters started to dwindle, making it necessary to search deeper for the shells and for divers to use diving equipment.

This time, the perilous job of using the underdeveloped gear was given to indentured labourers from Asia — Japanese, Chinese, Malays, “Koepangers” (from modern-day East Nusa Tenggara) and Filipinos — employed by Broome-based pearl lugger operators, which by then numbered in the hundreds.

These labourers made up a significant portion of Broome’s multicultural, and later racially segregated, population. By the time Broome’s pearl-shelling era peaked in the early 1900s, the Asian population outnumbered the European contingent by three to one.

Outdoor cinema: Sun Pictures, established in 1916, is the world's oldest operating picture gardens. (JP/Prapti Widinugraheni)It was Broome’s heyday and the town flourished with entertainment establishments such as Sun Pictures, an open-air cinema that opened in 1916 and still operates to this day.

This boom, however, came at a cost: the dangerous conditions faced by the divers and a lack of scientific knowledge supporting them meant that many lost their lives on the job. Broome’s cemetery, which is segregated into sections containing Chinese, Japanese, Muslim and Jewish gravesites, is testament to the industry’s bittersweet past.

Broome’s pearl-shelling industry slid into decline with the bombing of the town by Japanese aircraft in World War II and, later, with the invention of plastic buttons, which took over the use of pearl shells.

A slight revival occurred when the industry’s focus shifted from the trading of shells, or mother-of-pearl, to pearls, and today, Broome’s pearl industry consists largely of pearl-farming enterprises and related tourist activities.

Broome’s historical encounter with “foreigners” was in fact not limited to its pearl industry.

Past connection: The red archway to Johnny Chi Lane marks Broome’s links with Asia. (JP/Prapti Widinugraheni)Cable Beach, which faces the Indian Ocean, was named after an undersea telegraph cable laid in 1889.

The 1650 km cable connecting Broome to Banyuwangi in East Java operated for over two decades and elevated Broome’s status from a shoddy “campsite” to that of a functioning town before it became obsolete following the installation of a newer cable crossing the Indian Ocean and terminating closer to Perth.

These days, the town of Broome is home to a population of mixed European, indigenous and Asian heritage. It is also frequented by indigenous people making journeys from their homelands.

And though the days of a thriving multicultural society are gone, the town still attracts “outsiders.”

Unlike their predecessors, today’s outsiders are less concerned with pearls than with the beauty of the Kimberley landscape, Cable Beach’s sunsets, Roebuck Bay’s mudflats and red moon-rises. The fact that so much of the town’s activities are governed by enormous tidal movements — very little has changed since the dawn of time.