Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsCreating legal safe harbor for netizens, platforms

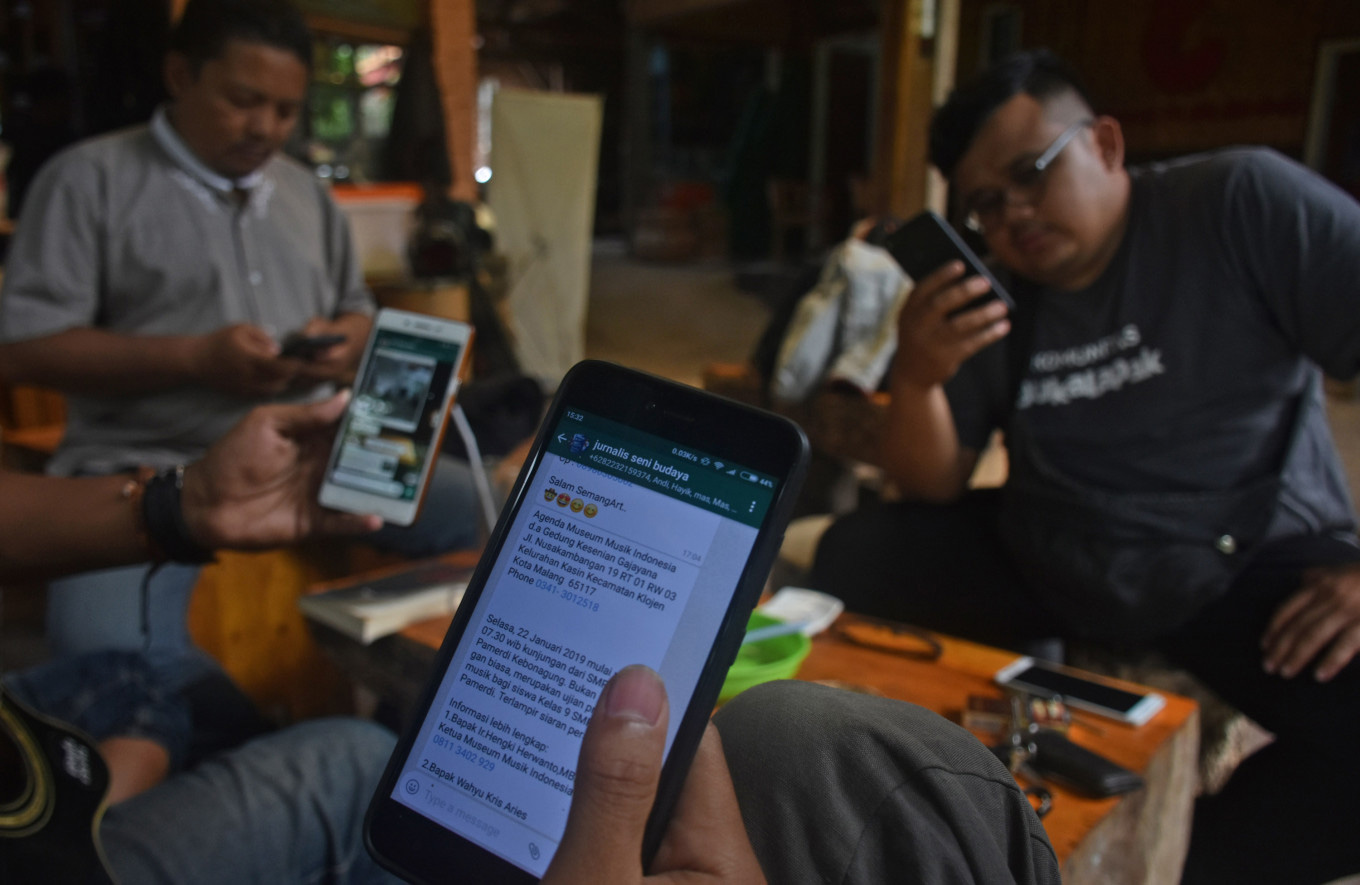

Indonesia currently ranks third worldwide in terms of the number of Facebook and Twitter users. Successful moderation will require machine learning. The major social media platforms have this technology, but unfortunately, these algorithms were “raised” in English. None has developed true facility in Indonesian.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

Indonesia currently ranks third worldwide in terms of the number of Facebook and Twitter users. Successful moderation will require machine learning. The major social media platforms have this technology, but unfortunately, these algorithms were “raised” in English. None has developed true facility in Indonesian. (JP/Aman Rochman)

Indonesia currently ranks third worldwide in terms of the number of Facebook and Twitter users. Successful moderation will require machine learning. The major social media platforms have this technology, but unfortunately, these algorithms were “raised” in English. None has developed true facility in Indonesian. (JP/Aman Rochman)

I

nternet access in Papua has been limited for a “temporary” period these past weeks since student demonstrations erupted in August, followed by riots in which dozens were reportedly killed. Massive demonstrations in Jakarta and other cities also led to rumors that access to Twitter was being limited, which authorities denied. Greater distrust in the government is looming.

Before that, we learned of the case of Baiq Nuril. Faced with persistent sexual harassment from her boss, the woman decided to record the lewd comments he made to her over the phone. When she shared this recording online with a colleague, her act of self-defense finally led to a sentence of six months in jail with a fine of Rp 500 million (US$35,755) for defamation under the Electronic Information and Transactions (ITE) Law.

This 2008 law is remarkable for its breadth, with its mandate to suppress defamation, hate speech, pornography and other rather vaguely defined types of expression, and fails to adequately distinguish between well-meaning whistleblowers like Nuril and potentially dangerous public figures like rock star turned politician Ahmad Dhani, who was sentenced earlier this year for his viral internet posts against “blasphemers”. Though in July Nuril was granted amnesty, the hundreds of other individuals who have been convicted under the cyber law have not been so fortunate.

In practice, the law only holds individuals accountable. The platforms these people use to disseminate their speech are left out of the equation, even as those platforms profit from that content.

Consider the earlier case of Florence Sihombing, a student who was convicted under ITE for “defamatory” complaints offending residents of Yogyakarta, that she posted on Path in 2014. Florence’s comments, apparently triggered by a long gas station line, were no different from the day-to-day griping we all engage in. The only thing that distinguished them from a verbal complaint to a friend was the potential virality that electronic communication facilitates. If the government sees it fit to censor legitimate grievances, the least it could do is focus its attention on the actor who enables the ostensible damage — the platform. Yet, Path faced no consequences for the message it circulated.

The government approaches online speech issues with a sledgehammer when a scalpel is more appropriate. When it comes to the troublesome content ITE was designed to remedy, the authorities see just three options: punish individual users, ban the website or platform where the content was posted, or worse, limit the general public’s internet access.

Let’s take a page from Germany, which last year enacted the Network Enforcement Act. Under its terms, if a user issues a formal complaint about an internet post, the platform has 24 hours to determine whether that post violates German law and, if so, to remove it.