Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsMaking drugs affordable

In this critical juncture, the race to find medicines can easily turn into a competition to control access to the drugs.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

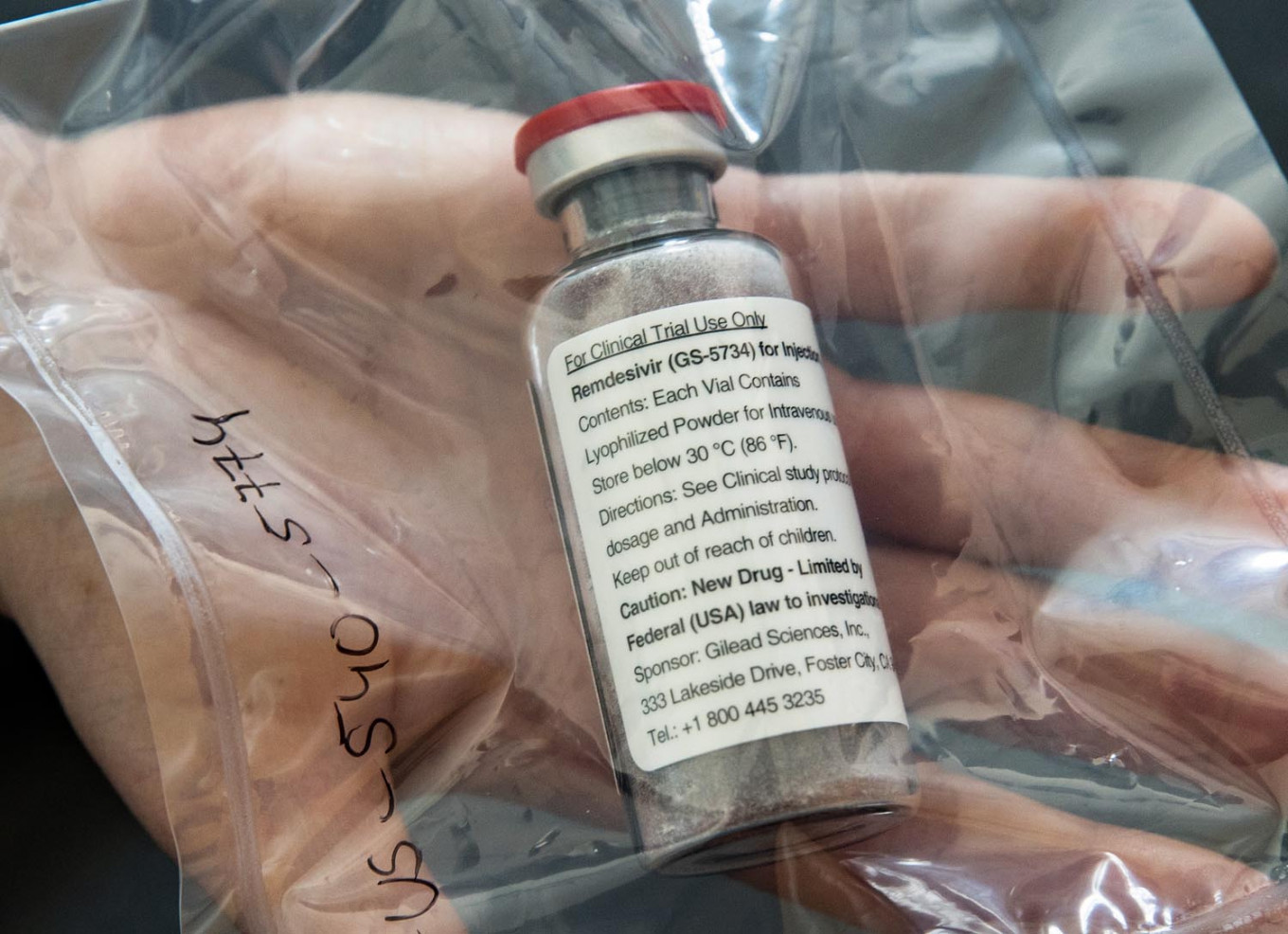

In this file photo taken on April 8, 2020 one vial of the drug Remdesivir lies during a press conference about the start of a study with the Ebola drug Remdesivir in particularly severely ill patients at the University Hospital Eppendorf (UKE) in Hamburg, northern Germany, amidst the new coronavirus COVID-19 pandemic. - The experimental drug remdesivir has been authorized by US regulators for emergency use against COVID-19, President Donald Trump announced on May 1, 2020. (AFP/Ulrich Perrey)

In this file photo taken on April 8, 2020 one vial of the drug Remdesivir lies during a press conference about the start of a study with the Ebola drug Remdesivir in particularly severely ill patients at the University Hospital Eppendorf (UKE) in Hamburg, northern Germany, amidst the new coronavirus COVID-19 pandemic. - The experimental drug remdesivir has been authorized by US regulators for emergency use against COVID-19, President Donald Trump announced on May 1, 2020. (AFP/Ulrich Perrey)

E

ntering the fifth month of the global COVID-19 outbreak, countries have been doing their utmost to control the rate of infection, and some are now preparing to return to normal life.

But people remain vulnerable because a cure has yet to arrive, and just like other viral diseases, COVID-19 will continue to devastate communities if they ignore social distancing and other precautionary measures.

Under a program called Solidarity Trial, the World Health Organization has organized clinical trials for four medicines and has tracked the progress of candidate vaccines to ensure governments, companies and research institutions cooperate to protect the world from the virus.

Remdesivir, a drug produced by pharmaceutical company Gilead Sciences, has shown, so far, most progress among the tested antiviral drugs. It may not cure COVID-19, but studies have found that it accelerates the recovery by 30 percent and decreases the likelihood of dying from the virus. The United States Food and Drug Administration has granted permission for its emergency use for COVID-19 treatment in the country.

Although not among those tested by the global health body, Avigan, developed by Fujifilm Holdings, is also close to approval in Japan as Prime Minister Shinzo Abe said the government would speed up a process that would normally take months.

None of the drugs have been certified as a magic pill to cure the disease, since they have only passed preliminary testing in trials that normally take months or even years. With more than 3.5 million cases and over 240,000 deaths worldwide, governments are under pressure to find a solution soon – not later. And in this critical juncture, the race to find medicines can easily turn into a competition to control access to the drugs.

This is why it is paramount for the WHO, along with governments, companies and international philanthropic organizations, to keep options open for countries. A supply of medicine can be exchanged for joint research and data access with receiving countries. Philanthropic organizations can help countries, particularly low-income ones, procure the drugs.

Indonesia has, so far, secured supplies of chloroquine and Avigan to treat COVID-19 patients. The Eijkman Institute for Molecular Biology, the government’s research arm, has submitted the first three complete genome sequences of the Indonesian strain of the virus to GISAID, a public-private partnership with the German government.

State-owned pharmaceutical company PT Bio Farma is also working with the institute and a number of international partners to develop a blood plasma treatment, also known as convalescence plasma, to help patients with moderate symptoms. Bio Farma is also hoping to work with the Bill Gates-backed Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI) and with Chinese vaccine producer Sinovac Biotech to produce a vaccine in Indonesia, where the virus has infected over 12,700 people and has killed more than 930.

The government should be open to additional alternative parties to make more treatments available to patients. While there is no clear end to these dark times, we must keep searching for the light – for everyone.