Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsIs there a new wave of inflationary risk?

Even for most developing countries such as Indonesia, inflation is not the primary concern of most economists anymore.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

E

conomists believe that inflation is something that only existed in the past and in most advanced economies, it is safe to say that inflation is dead. International Monetary Fund data shows that the inflation rate in high-income economies has been steady at below 3 percent since the mid-1990s, only breaching to above 4 percent during the 2008 global financial crisis.

Even for most developing countries such as Indonesia, inflation is not the primary concern of most economists anymore. Data shows that inflation stood at 1.59 percent year-on-year in November 2020. The figure was also manageable in December 2019, at 2.72 percent, before the pandemic – that caused the economic slump – started.

As a matter of fact, Bank Indonesia (BI) has been achieving its inflation target range (currently 3 percent ±1 percent) since 2015, which gives the central bank more room to focus its policy-making area on other compartments, such as financial stability.

However, recently, many economists have started expressing their concern again about the increasing inflationary risk after the pandemic.

There are a number of factors that can cause higher inflationary risk in Indonesia during the post-pandemic era. The first one is higher inflation expectations. As governments across the world slowly tame the adverse effects of the pandemic, economic activities will return to their normal state. Consequentially, income will rise and demand for products will recover. However, production usually lags behind and, thus, the supply cannot catch up as quickly to meet the recovering demand.

Due to this factor, people usually expect an increase in prices, which results in higher inflation expectations that are usually a self-fulfilling prophecy. Research by the Bank of England using data from 800 years ago suggests that inflation usually surges in the year following the start of a pandemic.

Another factor is more policy-driven. During the pandemic, many economies across the globe implemented fiscal and monetary easing to prevent further economic calamity. Indonesia is not an exception.

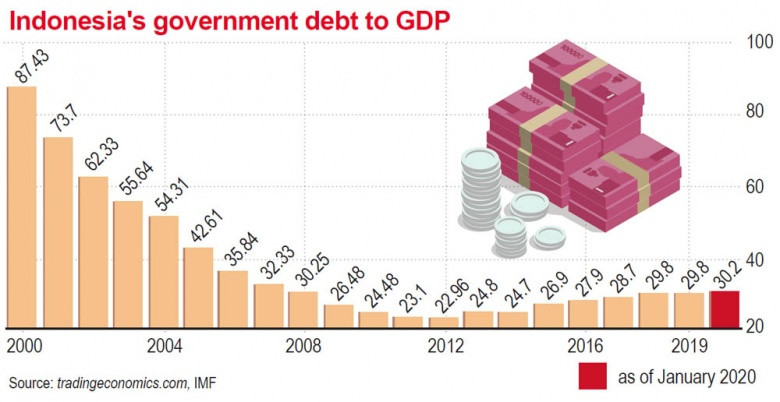

Indonesia’s public debt has been proliferating in recent months to cope with the pandemic. The public debt to gross domestic product (GDP) ratio (public debt ratio) has risen from 29 percent in 2018 to above 30 percent since the pandemic started. In August 2020, Fitch Ratings, an international rating agency, reports that Indonesia’s public debt ratio will reach its peak of 39.1 percent in 2022.

Simultaneously, the central bank has also been buying a vast amount of public debt as part of its monetary expansion and burden-sharing policy with the government. These are policy responses aimed at preventing the looming economic slowdown caused by the pandemic.

Some economists point out that the third factor that can cause a surge in inflation after the pandemic is the demographic reason. Charles Goodhart, a respected economist and ex-Bank of England policymaker, and Manoj Pradhan, a former investment banker from Morgan Stanley, recently published a book, titled The Great Demographic Reversal, that suggests the aging population can lead to structurally higher inflation in the long-run.

An aging population leads to a labor shortage and lower productivity, which eventually creates inflation. Fortunately, Indonesia is still endowed with a young population, so the third factor is not our urgent concern in the medium-term.

Therefore, policymakers can focus only on the first and second factors. The good news is, different from the third factor, the effect of the first and second factors may only last in the short-run or are temporary. After a rapid jump in demand, production will eventually catch up and the supply of products will increase, thus reducing the supply-demand mismatch and lowering inflation expectations. Similarly, as the economy recovers, the central bank may slowly downscale its monetary expansion, while the government may reduce its debt issuance and fiscal expansion.

Nevertheless, the risk of this inflation threat still cannot be downplayed. Due to the ballooning government debt during the pandemic, a surge in inflation may deteriorate the government’s fiscal health even further and prolong the process of economic recovery. Inflation also diminishes purchasing power, which eventually slows economic growth.

Both the government and the central bank have to be aware of this risk. An immediate policy response is necessary to curb any potential surge in inflation. From the central bank’s side, this can be achieved through monetary tightening and controlling core inflation. Meanwhile, the government can manage administered and volatile prices by ensuring a steady supply of goods when the demand starts increasing again.

***

The writer is a doctoral researcher at the University of Birmingham.