Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsDoes the teacher training curriculum really need revising?

In Indonesia, changes to the curriculum are often influenced by changes in domestic politics.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

“We have spent months on developing teaching materials and implementing them. It turns out that, in the end, our fate is determined by the knowledge test.”

That’s the view expressed by a dejected student enrolled in the Teachers Professional Education (PPG) program, who failed the final test. Since the program was launched by the government for teachers to obtain professional teaching certificates – and government incentives, PPG certification is highly coveted among teachers. Current and aspiring teachers compete to enter the program, and they have to work hard in the course of the program because of the tight schedule and wide curriculum.

At the end of the program, almost half of the students fail the final test.

The disappointment expressed by the student above begs the question as to what has gone wrong with the program. Is its curriculum properly designed to create professional teachers? Why is the failure rate so high? Are Indonesian teachers really facing a problem in becoming professional?

Compared with teachers in other countries, Indonesian professional teachers have a unique definition. That is because the educational circumstances in the country are highly dynamic, if not unpredictable. Everybody knows that the Indonesian curriculum has often changed, as opposed to that of Finland, a country prominent for its high educational standards, which changes the curriculum only every 12 years. Of course, we can argue that Indonesia is beyond comparison with Finland because of distinctive geopolitical situations.

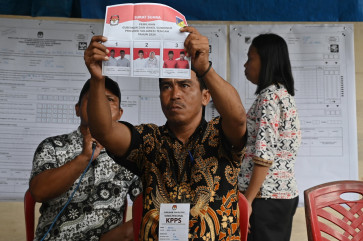

In Indonesia, changes in the curriculum are often influenced by changes in domestic politics. When the president changes, the curriculum follows suit. Even if there is no new national leader, the curriculum still could change if a new education minister assumes office.

As a result of the frequent changes, Indonesian teachers often feel overwhelmed. Especially if the curriculum requires them to be innovative and creative, as is the case with the 2013 curriculum that is currently in force.

Some teachers will motivate themselves to adapt to the changes, but most may resist and stick with the old way of teaching. This resistance is what the PPG deems a key task to solve in order to improve Indonesian teachers.

As a PPG instructor, I initially questioned the design of the PPG curriculum, because I witnessed PPG students spending more time to develop teaching devices such as lesson plans, learning media, student worksheets, teaching materials and evaluation sheets. Those make up about 80 percent of the PPG program. The PPG students work on it and implement it at schools.

Then, I asked myself, does this mean that being a professional teacher in Indonesia only requires skills in developing and revising teaching devices?

However, after years of experience as a PPG instructor, I realized that this is the core of being a professional teacher in Indonesia. Before PPG students develop their teaching devices, they have to study and analyze the given curriculum documents. They are challenged to set aside teacher and student text books provided by the government. Instead, they have to depart from the basic competencies and have to reformulate and reconceptualize the learning indicators and outcomes. They have to dare to say no to the prototype materials provided by the government if they do not suit the specific characteristics of their schools or their students.

This is actually a basic competence an Indonesian professional teacher should have. So, whatever the curriculum looks like, and regardless of how fast it changes, an Indonesian professional teacher has to have the confidence and guts to examine, analyze and adjust the curriculum materials to fit the real conditions they face at school. Such competency is more crucial than ever now that we are facing a pandemic that has forced schools to close.

Furthermore, during the device development workshop, PPG students have to compile a classroom action research (CAR) proposal. What is interesting about the concept of the CAR, which is packaged and discussed during the PPG lecture and teacher training organized by the Tanoto Foundation, is the idea of CAR as a process to improve teachers’ performance on an ongoing basis.

CAR for PPG students is not packaged as a research concept discussed in higher education. Rather, it is initiated to record the process of planning, implementing, observing and reflecting on class materials, which allows a professional teacher to create a follow-up plan on a daily basis.

Thus, with this continuous CAR, it is hoped that PPG students will be equipped to become professional teachers who are accustomed to reflecting on what has been done in class and constantly improving their performance based on the results of these reflections. At my institution, Surabaya State University, such continuous CAR has been adopted into what we call Continuous Improvement of Instructional Quality (CIIQ).

Based on my field experience, the device development workshop and its implementation at school as continuous CAR or CIIQ deserves more emphasis in the PPG program than other curriculum materials. As a consequence, the percentage of passing evaluation should be adjusted as well.

For the sake of fairness for PPG students, the passing grade should depend at least 80 percent on the ability to develop and implement teaching devices, while the remaining 20 percent of the passing grade could be taken from the final knowledge test, because students spend only about 20 percent at the beginning of the program on acquiring pedagogical and content knowledge.

***

The writer is a lecturer of the Elementary Teacher Department and a Teacher Professional Education (PPG) instructor, Surabaya State University. The views expressed are her own.