Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsAgainst all political and religious odds

A book discussion shares an effective way to fight social discord stemming from political and religious differences.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

W

ith the upcoming gubernatorial election in Jakarta, many have seen escalating disagreement among people across religious and political lines, particularly on social media, where people become engaged in heated debates and many netizens add fuel to the fire by spreading false news and incendiary information.

This is why American social psychologist Jonathan Haidt’s 2012 book The Righteous Mind: Why Good People are Divided by Politics and Religion (Vintage Books) is a timely read.

To provide wider comprehension of the book, Tempo media group, with bookstore Periplus Indonesia, organized a discussion called Bangsa yang terbelah: refleksi menguatnya intoleransi (A Nation Divided: Reflections on Growing Intolerance) late last month.

The discussion featured Jaringan Gusdurian national coordinator Alissa Wahid, Driyarkara philosophy academy boarding house advisor Greg Soetomo, as well as Nurcholish Madjid Society foundation head Muhamad Wahyuni Nafis. The discussion was moderated by senior Tempo media group editor Hermien Y. Kleden.

All speakers in the forum expressed concern over increasing bigotry and conflicts created by political and religious beliefs in Indonesia.

Quoting her late father, the late former Indonesian president and prominent Nahdlatul Ulama (NU) scholar Abdurrahman Wahid, Alissa warned of the “Talibanization” of the country.

“[The Talibanization of Indonesia] hasn’t happened yet, but there is a stronger tendency toward religious-based disunity,” Alissa said.

Read also: Indonesia's Pakistanization: 'Your cousins are your potential enemies'

Muhamad, on the other hand, warned that the true test to our unity as a country would not happen in February’s Jakarta gubernatorial election but instead during the 2019 presidential and legislative elections.

“Today’s condition can sow the seeds of conflict [in 2019]. We have learned from history that the first and biggest horizontal conflict happened when Muslims fought Muslims,” Muhamad said, referring to the Sunni-Shia schism following the death of Prophet Muhammad in the year 632.

The most puzzling thing about the current political religious “war” is how many people seem to have lost reason, with many highly educated people trading bitter condemnations against others who are religiously and ideologically different through social media handles or WhatsApp groups.

“Many people have wondered, how come people who are highly educated, who earned degrees in the United States, for example, fall into the trap of bigotry? All this time, people somehow assume that knowledge broadens people’s minds to be more open, but [Haidt explained that] it’s not true,” Alissa said.

Haidt concludes in the book that the more advanced an individual’s rational thinking capabilities, the more capable they are of justifying their harmful actions.

Read also: Managing communist-phobia in Indonesia

Citing several examples, the writer argues that morality is not guided by rational thinking but by intuition. This is why religion and politics are so divisive, because they touch upon our gut feelings. Humans are governed by six pillars of value, a spectrum that varies in proportion according to different ideological leanings: care/harm, liberty/oppression, fairness/cheating, loyalty/ betrayal, authority/subversion and sanctity/degradation.

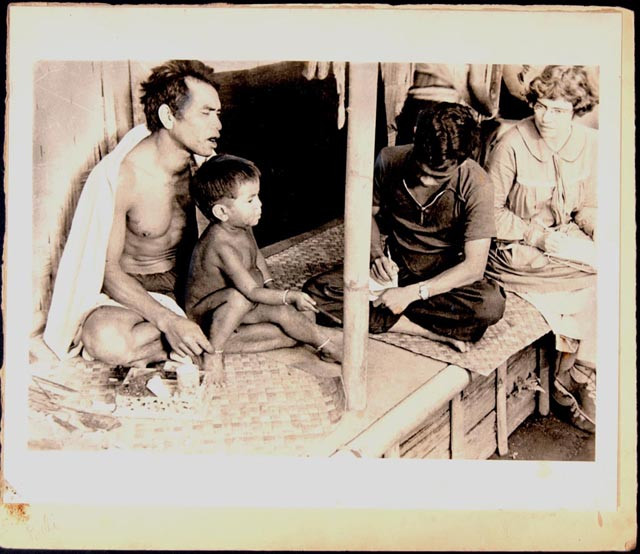

This is why, according to Haidt, to effectively combat bigotry, one needs to have immersive experience in a different environment from her/his religious and cultural backgrounds.

He cited his own experience when his empathy for America’s Republicans rose after living with religiously conservative people in India.

“You don’t have to devise ambitious projects to counteract bigotry and prevent conflict. You just need to communicate with people across different religions and ethnic groups and create discussions with them and let your circle expand,” Alissa said, echoing Haidt’s notion of immersion.

Greg Soetomo, however, added some caveats against the book, arguing that it did not present a balanced multidisciplinary approach in discussing the issue of religious and political divisiveness.

“The book is poor in references to sociology or politics, particularly in terms of field research results from both fields. As if these subjects have been ‘swallowed’ by its philosophical and psychological approach,” Greg said.

This is where Muhamad shared his political and social understanding on the issue, filling the gap left by Haidt.

“Do people become religiously intolerant because of religious [dogmas] or because of social, political and economic variables?” Muhamad pondered during the discussion. “If you look at religious extremists who become ‘brides’ [hard-liner term for suicide bombers], you will become aware that their lives are destitute.”

Therefore, Muhamad believes it is unfair to create stereotypes in observing bigotry.

“It’s inaccurate to depict Islam as an agama keras [tough religion] because we know that terrorism exists in every religion. Terrorism has more to do with human beings’ sikap batin [spiritual attitude], embodied characteristics like petty-mindedness and the desire to take shortcuts in solving problems,” Muhamad explained.