Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsExamining Indonesia's collective trauma

A book has collected memories of the 1965 tragedy to be passed on to the next generation.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

Y

ears after the 1965 tragedy, which started with the kidnapping and murder of several military generals, the issues remain sensitive.

The now-defunct Indonesian Communist Party (PKI) was blamed for the killings. Revenge by the military caused the deaths of between 500,000 and 1 million alleged PKI supporters in many parts of the country. Millions of people were also imprisoned without trial.

Those responsible for the tragedy have never been brought to justice. Until today, there is intimidation and increasing attempts to shut down books, films, plays and discussions on the issues.

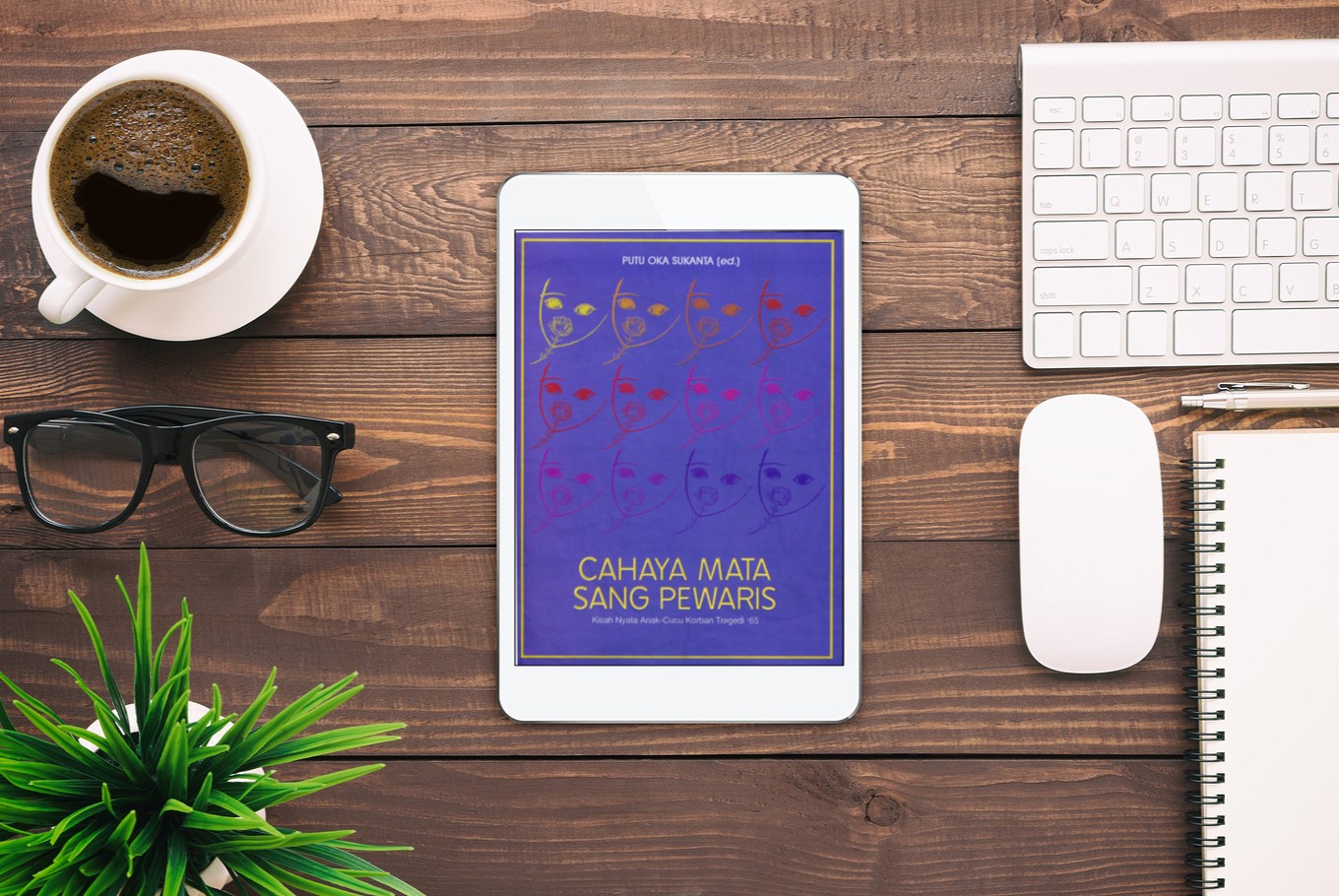

Through a new anthology, titled Cahaya Mata Sang Pewaris: Kisah Nyata Anak-Cucu Korban Tragedi ’65 (Glimmers in the eyes of the heirs: True stories from children and grandchildren of the ’65 tragedy), Balinese artist and writer Putu Oka Sukanta has put the spotlight back on the issues.

The writer, an activist who has tirelessly pushed for reconciliation surrounding the tragedy, was a political prisoner incarcerated from 1966 to 1976 without trial for his involvement with the now-defunct leftist artists association Lekra.

He has edited the anthology, published by Ultimus, which features testimony from 25 individuals, who are second- and third-generation family members of the 1965 victims.

They are Astuti Ananta Toer, Awal, Dhianita Kusuma Pertiwi, Efdi, Fidellia Dayatoen, Gita Laras, Gusti, I Wayan Willyana, Ieda Fitriani, IGP Wiranegara, Karina Arifin, Konrad Penlaana, Mado, Nasti Rukmawati, Ni Wayan Sinten Astiti, Nurhasanah, Phoa Bing Hauw, Putranda, Siauw Tiong Djin, Soe Tjen Marching, Sono, Syafrina Alam Sitompoel, Tuti Martoyo, Uchikowati and Wangi Indria.

Some of them wrote the stories themselves; others were helped by interviewers who listened to their stories and subsequently put them on paper.

“[Indonesian heroine] Kartini said ‘after darkness, let there be light.’ Unfortunately, though, in Indonesia, the darkness that covers our history never seems to fade. This is why we have to continue our efforts to find some ray of light,” Putu said during the recent book launch in GoetheHaus Jakarta.

“[The powers that be] still cast dark shadows over our cultural and legal rights. Therefore, let us join a collective effort to make our cultural rights a reality.”

Read also: From victims to survivors: The healing journey of the Dialita choir

Putu said to make the dream a reality, the counter-narrative about the 1965 tragedy had to be preserved to be passed down to the younger generation. “I hope the younger generation will continue our struggle,” he said.

Echoing Putu’s notions of involving the younger generation, during the launch event, a 1961 clip of a speech by former attorney general of the Hessen state of Germany, Fritz Bauer, pushing for the bringing of those complicit in the Holocaust tragedy to justice, was also screened.

“I believe that Germany’s young generation is ready to know the complete picture of history and the truth, but sometimes their parents still find it difficult to accept and overcome such a burden,” Bauer said in the speech.

Putu’s biographer, Okky Tirta, questioned why Indonesia could not follow Germany’s footsteps in overcoming its political trauma, considering that both the Holocaust and 1965 tragedies could be said to represent equally dark chapters of both countries’ respective histories.

“Germany has now moved on to a different political constellation and Indonesia is still pretty much in the same repressive constellation,” Okky said during the discussion.

The stigma for 1965 victims still persists until today. Despite this, the writers do not attempt to drown in self-pity or bitterness but instead tell stories of how they turned their lives around and reclaimed their dignity in the aftermath of the tragedy.

Gita Laras, member of the all-female Dialita choir made up of 1965 survivors, for example, tells a poetic story of how the arrest of her father destroyed her happiness and how she became a phoenix out of the ashes through her singing activities with the musical group.

She said that in Sanskrit, the name Gita Laras means “harmonious songs.” The 1965 tragedy had temporarily taken the “s” out of her second name — turning her into gitalara, which in Sanskrit means “songs of sorrow.”

Having worked through being a victim and stigmatized by other people, Gita said she now realized people must not succumb to the narrative created by history’s victors but reclaim their dignity.

“Having realized that, I have now reclaimed the name Gita Laras again,” she writes in the book.

A story from another family member called Gusti, whose father was also a political prisoner, has an empowering title: Menaklukkan Penistaan (Conquering Humiliation), which tells of how his parents worked hard, against all odds, for him to get a higher education as they believed education could restore their son’s dignity, regardless of societal stigma. And it did.

Although the writers admit to fearing for their safety after having their stories published, as a result of the still prevalent stigma about 1965 survivors, they said they had pushed through their fears because they felt as though writing the book was the right thing to do.

“Pak Putu told me not to write my story in a way that was full of grudges. But we must tell our stories so that such tragedies will not happen again,” Wiranegara said.

In her introduction to the book, Nani Nurrachman Sutojo, who is a daughter of the kidnapped and murdered Gen. Sutoyo Siswomiharjo, echoed Okky’s ideas.

She said that trauma was not something to be feared — if properly processed, trauma could be a “great asset” for the nation as it could help society to ask the question, “what really happened to us?”

“The next question, which is very important because it could help a nation’s advancement, is: ‘which direction will we want to take our country to in the future?’.”