Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

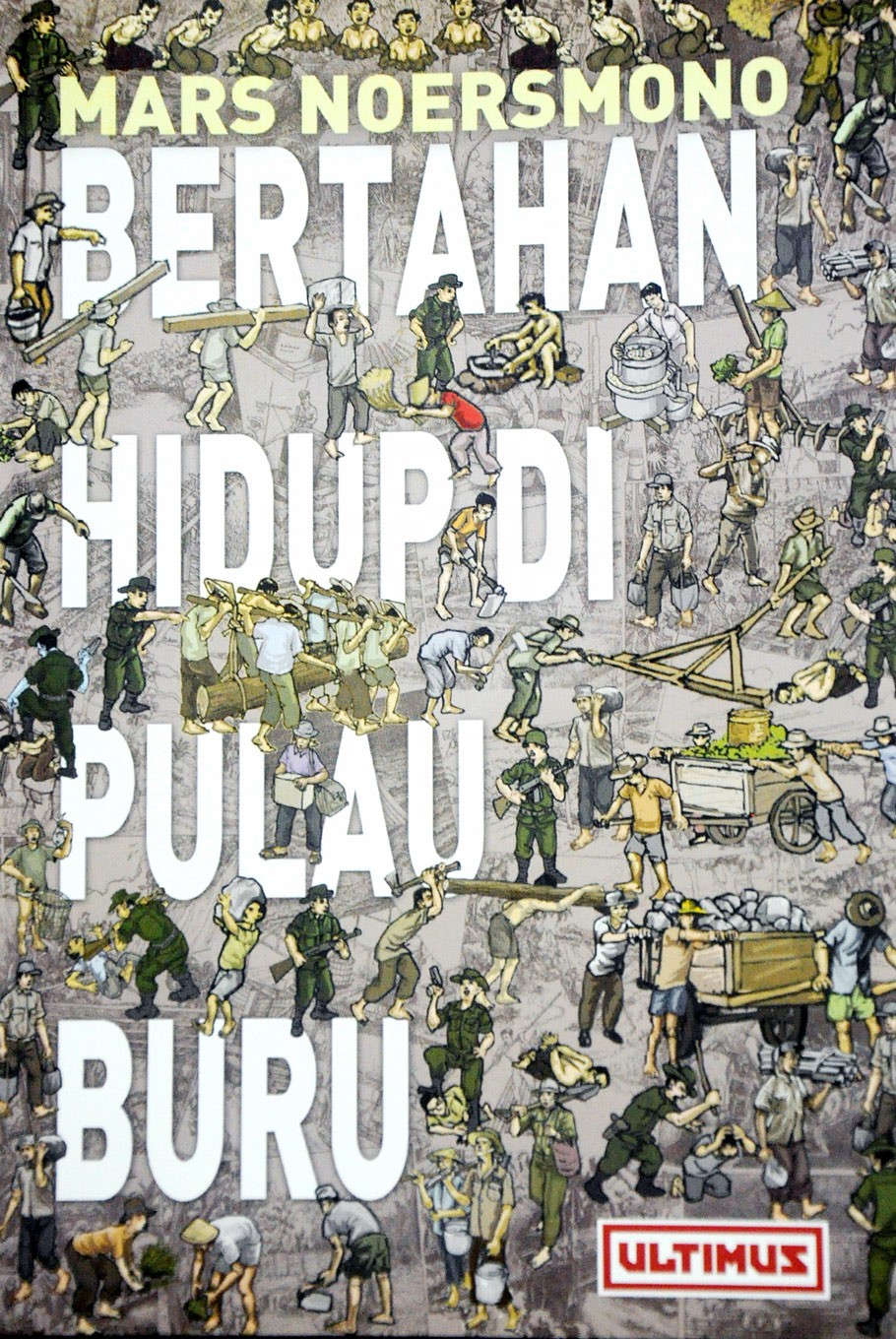

View all search resultsMars Noersmono: Surviving a harsh life on Buru Island

An insider’s illustrations and narration sheds new light on the dark history of a prison camp on Buru Island in Maluku.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

M

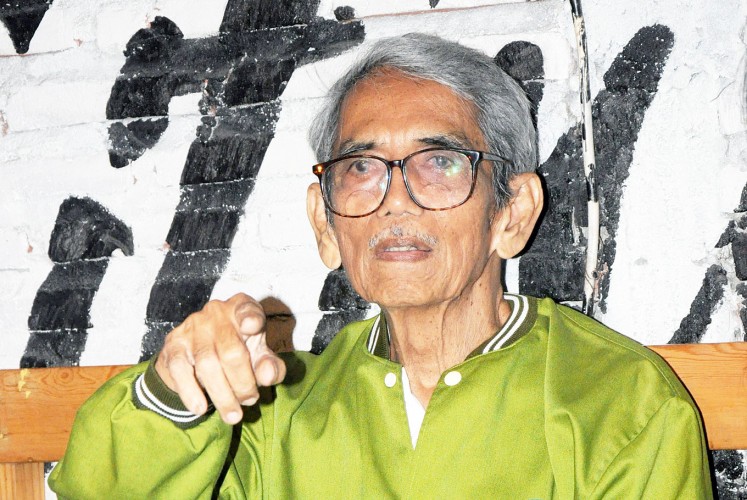

ars Noersmono might have a lean physique, grey hair and slightly trembling hands, but the 78-year-old remains strong, despite the soft tone of his speech suggesting otherwise.

“Sorry, I can’t speak at length without breathing properly,” he said during a discussion of his book Bertahan Hidup di Pulau Buru (Surviving on Buru Island) in Malang, East Java.

Noersmono is one of the survivors of political detainees held by the New Order regime. He was not an important figure when the political upheaval of 1965 occurred. Born in Jakarta, Noersmono was once a student at the Bandung Institute of Technology and a sympathizer of the Concentration of Indonesian Students’ Movement (CGMI), an affiliate of the Indonesian Communist Party (PKI). He was among about 11,000 detainees banished to Buru Island without trial over their connection with the now-defunct PKI.

“The island was called Tefaat Buru or ‘place of utilization,’ a name reflecting the desire of the ruling power to benefit from the detention camp,” he said, adding that the detainees, mostly coming from the middle segment of society, had been forced to turn the wilderness into farmland for growing crops.

Mars Noersmono, author of Bertahan Hidup di Pulau Buru (Surviving on Buru Island). Noersmono is one of the survivors of political detainees held by the New Order regime. (JP/Nedi Putra AW)Unlike novelist Pramoedya Ananta Toer, who authored four novels popularly called the Buru Quartet during his exile, Noersmono wrote the story of his life on the island in a unique way. As a former student of architecture, he made 75 detailed sketches of Buru and his various activities to accompany the narrative in his 368-page book.

He sketched and recounted how he jumped from the tank landing ship when he arrived on the island in 1971, reclaimed land for paddy planting, produced cajuput oil and survived by eating anything from larvae to rats.

“A plate of rice was a luxury at the time,” he said.

The suffering described by Noersmono goes beyond the scarcity of food, clothing and working equipment. He also revealed all kinds of harsh treatment of political detainees by camp guards, which made him a witness to the great despair of some of his fellow captives, who failed to endure the misery by ending their own lives.

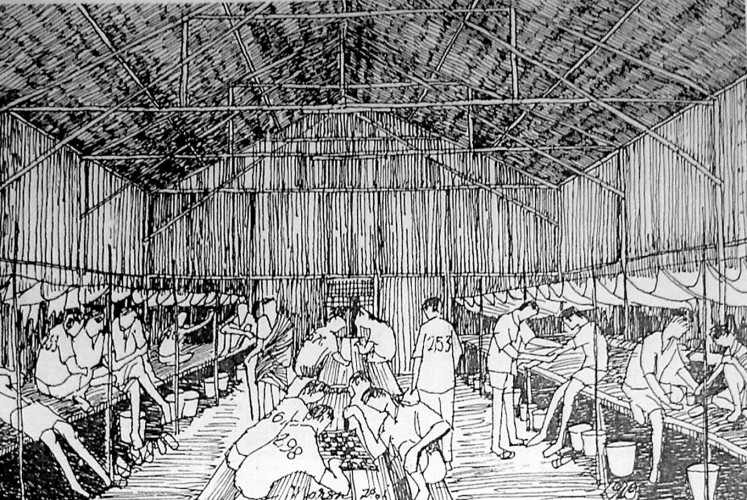

Noersmono explained that he had drawn the pictures from memory, because it was impossible to sketch while under detention. By creatively recollecting what he experienced from 1971 to his day of release in 1979, he made himself strong and optimistic enough to leave behind his painful past. His sketches serve as a practical historical document, as there are no books or records of pictures from Buru Island.

The grandfather of seven said he held no grudge against the New Order regime that had imposed a dark shadow on his life. His sketches were also made out of his childhood hobby of drawing.

Dark period: An illustration of accommodation for political prisoners on Buru Island in the book titled Bertahan Hidup di Pulau Buru (Surviving on Buru Island). (Mars Noersmono/File)“I don’t say anybody is to blame in this book. I just want to show that something went wrong in the country, and hopefully it won’t recur,” he said.

John Roosa, a historian and professor at the University of British Columbia in Canada, said political prisoners on Buru Island were subjected to terrible conditions.

“Buru Island was worse than the colonial exile camp in Boven Digul [in Papua], because Buru detainees had to work hard to meet their daily needs under limited conditions of land and equipment,” he said, adding that their harvests were also frequently seized by the camp unit commandant.

Roosa, who sat next to Noersmono during the discussion, mentioned three groups of detainees. Group A comprised of those to be put on trial, group B of those being charged and detained without trial and group C of those to be released. Most of the ones sent to Buru Island, including Mars Noersmono, belonged to category B.

“As initially planned by the New Order [regime], these Buru Island political detainees would remain there for an indefinite period until their demise,” Roosa said.

Harsh condition: After the morning ceremony, the political prisoners would pick their farming equipment in the warehouse and go to the fields. (Mars Noersmono/File)The author of Pretext for Mass Murder: The September 30th Movement and Suharto’s Coup D’Etat in Indonesia also pointed to international pressure, especially from the United States Congress during the administration of US President Jimmy Carter, which had led to the release of the detainees in 1979.

Roosa added that in 1977, when the uprising in East Timor was being stamped out, the New Order regime requested helicopter aid from the US.

“Finally both sides agreed that America was ready to provide aid on the condition that the human rights violation on Buru Island should be ended,” he said.

Roosa said he hoped Indonesia would learn from what had happened to Noersmono by respecting the law. He believes fair enforcement of the law is a strong foundation for democracy.