Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsNH Dini and her endless soul-searching journey

With dozens of best-selling and quality novels, short stories and poems to her credit, as well as several literary awards, prolific octogenarian writer NH Dini is at peace with herself.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

L

ooked after by the staff in a resort in the art village of Ubud, 81-year-old Nurhayati Sri Hardini Siti Nukatin — renowned by her pen name NH Dini, one of Indonesia’s living literary legends, sat in her wheelchair enjoying a sunny afternoon.

“I can still walk properly, but I am a little bit tired after a night-long ceremony at the Ubud Royal Palace,” she said as she got up from the wheelchair to walk toward the resort’s café.

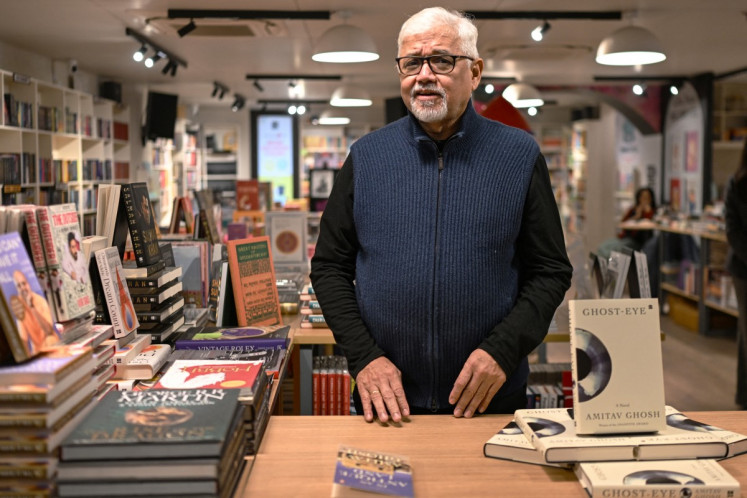

During the Ubud Writers and Readers Festival (UWRF) recently, the festival’s founder Janet DeNeefe presented NH Dini with the distinguished Lifetime Achievement Award for her more than six-decade literary career and her tremendous contribution to the development of Indonesian literature.

“The award really humbled me. For me, this is a recognition of a writer’s efforts, endurance, persistence and patience to stand tall on the fast-changing Indonesian literary stage,” as she shared her feelings and experience in that afternoon chat.

Standing tall, she says, is a strong ability required to survive in the writing world, where appreciation from the public, the book and publishing industry and the government, are lacking, if not absent.

“I have been writing since the early 1950s and will continue to write because writing is my profession. I earn money from writing.”

Born to the Javanese noble couple Salyowijoyo and Aminah on Feb. 29, 1936, NH Dini is the youngest of five siblings. She began writing when she was still at junior high school.

“It was my mother who kept encouraging me to write. My mother prepared a special room belonging to my late father together with his old Remington typewriter.”

With dozens of novels, short stories and poems to her credit along with several literary awards, including the SEA Write Award from the government of Thailand, people might think this prolific writer led a comfortable and prosperous life.

Far from a life of glamor, she is currently residing at Panti Wredha Langen Wedharsih, a decent home for the elderly in Ungaran, Semarang in Central Java.

“Honestly, I have neither savings nor health insurance. My insurance is my family, my friends and even doctors who have treated my illnesses,” said the writer, who had her uterus removed because of a cancer-related illness when she was 43. After returning to Indonesia, she frequently fell ill.

Compared to the life of writers in neighboring countries like Malaysia, NH Dini said a writer of her caliber would receive lifelong state funding. “Writers in Malaysia are highly regarded as the nation’s precious literary jewels. They are highly respected and are granted Datuk [honorary] titles, and are entitled to state financial support and other facilities.”

In Indonesia, on the other hand, writers are often considered second-class artists or scholars, she said. “This is the clear mirror on how the state and the people of Indonesia perceive literature,” NH Dini said.

“Literature is actually nutritious food for humans’ souls and minds. It is the basic foundation of humanity, a reflection of a society, reality, knowledge and wisdom, which many people including the government in charge of art and culture ignore.”

Book royalties and intellectual property rights have long been crucial issues for writers in Indonesia. “In the music industry, I heard there are some foundations and institutions helping artists acquire royalties and rights. I hope there are such institutions in the literary field.”

Back in the 1970s and 1980s, some of NH Dini’s novels were considered controversial for taking on taboo subjects like male and female relationships, sensuality and sexuality.

“In the 1970s and 1980s, my novels Pada Sebuah Kapal [On the Boat] and La Barka were banned from public school libraries as the novels could have negative impacts on young people, girls especially,” she said.

NH Dini was surprised when she was invited to visit a pesantren (Islamic boarding school) belonging to fellow writer Ayip Rosidi’s family. “This pesantren’s library had the two novels — Pada Sebuah Kapal and La Barka, each with five copies.”

Esteemed honor: Renowned writer NH Dini (center) is flanked by her son, filmmaker Pierre Louis Padang Coffin (left) and Ubud Writers and Readers Festival Founder Janet DeNeefe when receiving her Lifetime Achievement Award in Bali. (JP/Anggara Mahendra)All santri (students), she said, were required to read and to discuss the contents of the books to decide the positive and negative values. “I was so impressed. Rather than banning the books, this pesantren was open-minded in allowing its students to engage in discussion.”

Even the late Abdurrahman “Gus Dur” Wahid, Indonesia’s former president and chairman of the country’s largest Islamic organization Nahdlatul Ulama (NU) read those novels, she said. “When I asked him, Gus Dur just said the novels offered a lot to ponder.”

In these two novels, NH Dini features two female protagonists — Sri (Pada Sebuah Kapal) and Rina (La Barka), portrayed as women of Javanese descent, who dare to break the rules on the patriarchal concepts of women and wives.

In the Javanese concept of patriarchy, a women’s role is as a konco wingking, literarily meaning a partner in the house and bedroom. Their roles are limited to raising children and serving husbands and families — there is no place for them to be regarded as individual beings.

NH Dini’s female characters are always painted in opposition to this Javanese patriarchal concept of women.

“At that time, I did not relate my writings to the Western theory of feminism. What I strongly believe is that a woman, wherever she lives, deserves to be treated equally and respectfully. She should also have the rights to her own body.”

And her belief obviously comes across in almost all of her literary works. Her female characters are usually depicted as women who are eloquent in expressing their minds as well as their sexual desires; individuals who stand up for themselves against abusive husbands; and many times, they are pictured as unfaithful wives — all of these characterizations are associated with strict violations of traditional, social and religious norms.

NH Dini and her characters refuse to be passive individuals in a marriage.

“A marriage unites two different individuals in mutual affection and respect,” she says. “But when it fails, it is the woman who is blamed. When a husband cheats, a wife is expected to forgive. That is dehumanizing a woman. I don’t want to portray my characters succumbing to that situation.”

When asked about her failed marriage to French diplomat Yves Coffin, NH Dini is only capable of recalling sweet memories of their union.

“Yves was a romantic and gentle person. I was so smitten by his kindness and manner,” she said while remembering the first time they met in Jakarta when she worked as a flight attendant with Garuda Indonesia.

It was her uncle Iman Sudjahri that introduced them. Sudjahri was the father of respected scholar Edi Sedyawati, professor of archaeology. “She is my cousin and my best friend who is always beside me. We have been very close since we were teenagers as Javanese and Balinese dancers at the State Palace in the 1950s and 1960s.”

Despite family opposition to her foreign husband, NH Dini and Yves Coffin later got married in January 1960.

“My family said Yves was ‘kumpeni,’ referring to a Dutch colonialist.” The locals used to refer to any Westerners as kumpeni, regardless of their countries of origin. “Yves was a French citizen,” she laughed.

The couple had two children — Marie-Claire Lintang Coffin and Pierre Louis Padang Coffin. As a diplomat family, they lived in Japan, France, the United States and other countries.

“But, the romantic love did not last forever and it did not necessarily lead to a good marriage. After Padang was born, the passion dissipated. A man’s love is so short-lived, I just couldn’t understand.” The couple divorced in l984 and NH Dini returned to Indonesia.

“That was my life’s journey and I am very grateful no matter what. I have two adult children Lintang and Padang and beloved grandchildren even though they live so far away they are all in my heart.”

Padang, best known for co-directing the blockbuster Despicable Me moviefranchise, Minions among others, was present at the festival in Ubud when her mother received the award.

“I felt very touched when I heard Padang acknowledge during a joint interview that his artistic talent came from his mother — from me.”

Her daughter Lintang wrote in a commemorative book to celebrate NH Dini’s 80th birthday: “What I miss so much about my mother is her roaring laughter.”

Despite mountainous adversity, NH Dini is at peace with herself. “In the Javanese philosophy, a human being must be eling [alert], performing tirakat [continuous soul-searching] in order to humbly accept everything that comes to one’s life. It is the way I am now — a life full of gratitude.”