Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsBatik: The European connection

Cultural anthropologist and author Maria Wronska-Friend is a walking encyclopedia on Javanese batik.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

B

atik’s complex techniques and its rich visual vocabulary set Maria Wronska-Friend off on a journey to study every aspect of Javanese batik.

With over 30 years of researching Southeast Asia’s textiles, she went on to write several books and one of her best-sellers, which was published in Jakarta in 2016, is Batik Jawa bagi Dunia (Javanese Batik to the World).

Javanese batik, the pride of Indonesia, has been the subject of research by many historians from around the world. It is so exceptional that in 2009 it was placed on UNESCO’s List of Intangible Heritage.

Historical records and archaeological findings suggest that the wax-resist dyeing technique or batik may not be unique to Indonesia because for thousands of years it was practised in countries like China, Greece, India and South America.

However, it is Javanese batik that stands out as the most advanced form, both in terms of design and workmanship.

Studying people’s relationship with its material culture is indeed a very interesting approach to understand the history of mankind. The significance of material culture in Indonesia has been remarkable.

Classic: A dress from fashion house Lafarriere in Paris (1910) is decorated with two rows of elongated triangles that mirror the arrangement of a Javanese sarong skirt. (Maria Wronska-Friend/File)“Indonesia developed a very rich material culture and its elements became an important aspect of the country’s national identity,” said Wronska-Friend who is currently a senior research fellow at James Cook University in Cairns, Australia.

The author was recently in Jakarta to deliver a lecture at the Indonesian Heritage Society on the topic, “Inspiration and Innovation: Javanese batik in the Netherlands and Poland”.

Wronska-Friend’s PhD thesis was on Javanese batik and European art in the late 19th and early 20th century from the Polish Academy of Science in Warsaw.

She is a powerhouse of energy traversing continents from Africa to Asia in her quest for more knowledge on the impact of Javanese batik on textile traditions outside Indonesia. Yet, she humbly admitted that how even after so many years, she was still in the process of fully understanding the meanings and philosophy of Javanese batik.

Elaborating on how the batik technique reached Europe, Wronska-Friend said the credit for introducing Javanese batik to Europe in the last decade of the 19th century belonged to the Dutch, the then-colonial rulers of Indonesia. From Holland it spread to other countries, especially France, Germany and Poland.

“The interest in Javanese batik technique was immense across Europe. In the 1920s, thousands of artists, some of them very famous, practised the batik technique. It also became a fashionable female hobby,” she said.

Chris Lebeau, the Netherlands (1905). Batik on silk made using the 'sogan lorodan' method of Central Java. The cloth was used as one panel of a three part room divider. (Provincial Museum van Drenthe, Assen/File)In the second half of the 19th century many artists and craftsmen started to oppose the outcomes of the industrial revolution and the initial excitement about machine-made products was waning. This trend resulted in the appreciation and revival of handmade objects.

Due to the Netherlands’ relationship with Indonesia, a group of Dutch artists started to practice Javanese batik and introduced the technique into their projects, especially interior decoration.

The “batikomania”, as it was called, swept Europe in a big way. Books on Javanese culture have been published in almost every European language. Museums across Europe began to curate Javanese art.

“Many well-known European artists, who had no experience of the batik technique, became interested in Javanese batik and textiles,” Wronska-Friend said.

Artists like Henri Matisse, Glasgow architect Charles Rennie Mackintosh and Belgian designer Henry van de Velde are known to have used Javanese batik motifs in their work.

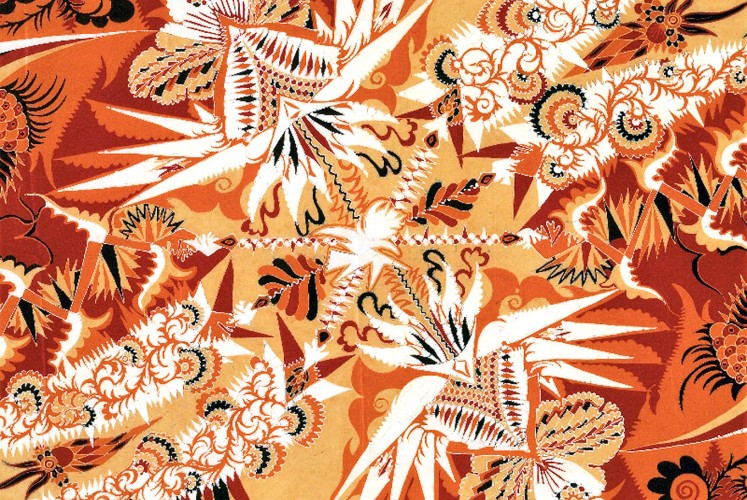

Ragnhild d’Ailly, the Netherlands ( 1928 ). Batik on silk shawl in Art Deco style. (Stedelijk Museum, Amsterdam/File)However, the adaptation of the Javanese technique in Poland has a very interesting history.

In Eastern Europe there is an ancient tradition of decorating eggs with wax-resist dyeing — a technique very similar to Javanese batik.

“Unlike the rest of Europe where batik fabrics resulted from the fascination with Oriental art, in Poland it was an ancient local technique that was transferred to cloth,” said Wronska-Friend.

The Poles consider batik on cloth to be an adaptation of this ancient, local tradition to a new material — from an egg shell to cloth.

“Yet, the Poles studied Javanese batik very closely. Polish batik created around 1910 to 1925 had an unmistakable Javanese character,” she added. These works were created by young art students who happened to visit an exhibition displaying Javanese batik.

It may be worth mentioning that batik is still very popular among the youth in Poland.

Up close: A woman stands in front of batik portraits of jazz musicians created by Polish teenagers from the Przasnysz Art Center in Przasnysz, a small town in north-eastern Poland. The portraits were made in 2015. (Maria Wronska-Friend/File)Regarding the difference between Javanese batik and batik in Europe, Wronska-Friend said, “While Javanese batik masters try to control the wax resist dye technique, in Europe the artists preferred to improvise.”

Batik is still hugely popular in Europe. Outside Indonesia, the batik technique, today, is estimated to be practiced by around 1,000 artists and craftsmen around the world. They have their own organization based in the United Kingdom — the Batik Guild.

“The works are very interesting in their own right, but in terms of aesthetics or technology, there are no Javanese connections,” Wronska-Friend said of batik practiced in Europe nowadays.

As a museum curator, she has organized over 10 major exhibitions to showcase Javanese batik. “Today, for many people, it is quite incomprehensible that one may spend weeks or even months to decorate one piece of cloth.”

Major museums in Europe have digitized their collections of Indonesian textiles to ensure that the art survives for years to come.

“I hope that one day museums in Indonesia, which have an excellent collection, will join this international movement,” Wronska-Friend said.