Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsShort Story: The Old Pu Tao

The tree was as old as its owner’s house.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

I

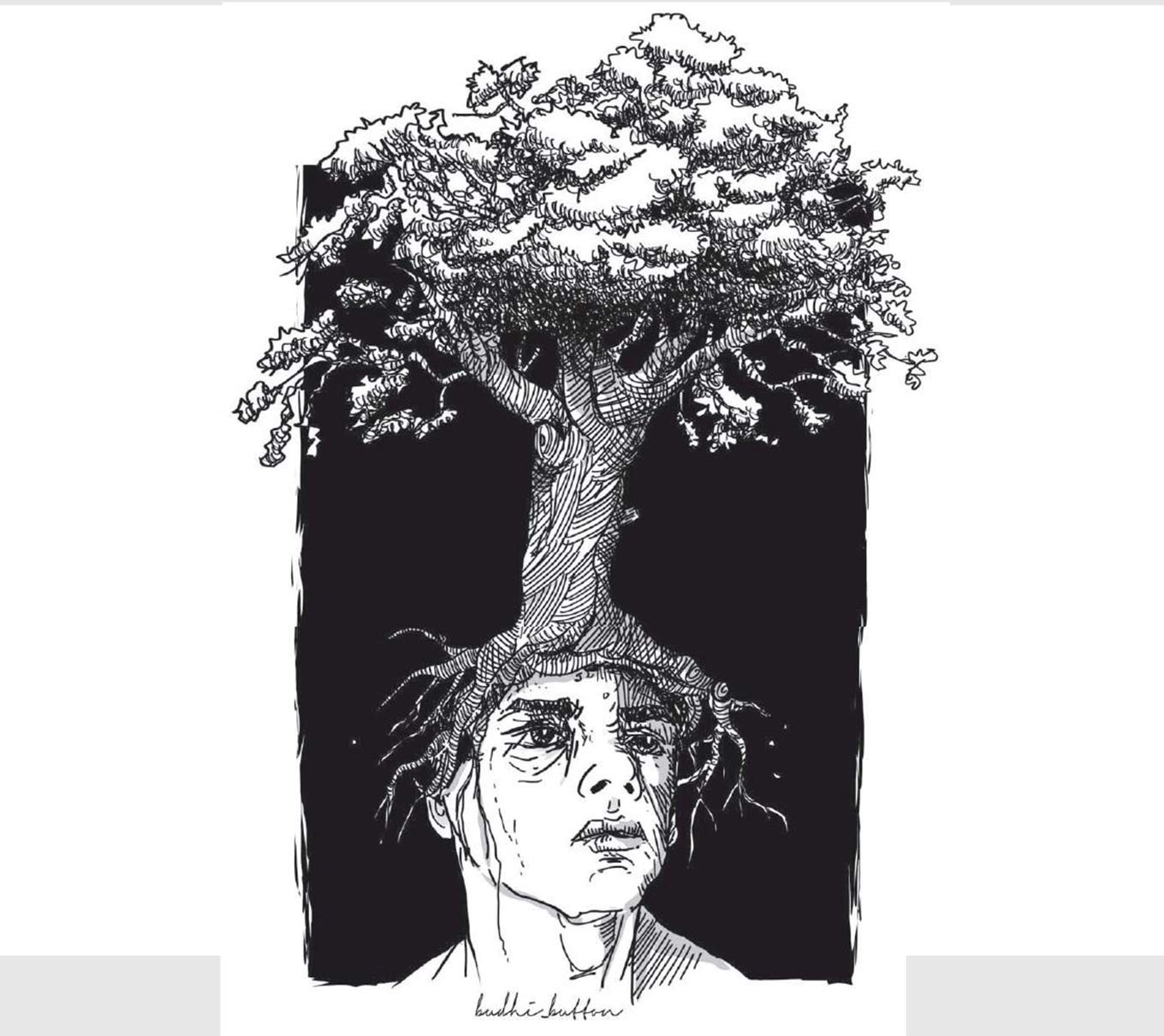

n Boneo’s front yard, a pu tao (Syzygium cumini) tree — better known as a jamblang (Java plum tree) — seemed to have trouble holding up its aging frame. The height of the trunk did not break the roofline of the house. Its branches created a thick canopy, but the foliage was dry; many leaves had fallen to the ground.

The tree was as old as its owner’s house. The house had originally been built with black tile flooring and walls made of jackfruit wood boards, but now it had a ceramic tile floor in a metallic color, brick walls and glass windows.

It had been a long time since the tree had borne any fruit. After it flowered, young fruit would fill the leafy canopy. Now, it was too weak to even bear a single fruit. And even if the tree had borne fruit, no one would be interested in eating them. The fruit was no longer served at the table; its sourness made it undesirable.

Even though the tree was old, Boneo had no intention of cutting it down. He still respected his mother’s advice.

Harmunik told Boneo not to cut the tree down before he got married and had his own family. After all, the tree was a living memory of his late father, as well as of Boneo’s birth.

His father had planted it when he found out his firstborn was a boy. A son would carry the responsibility of upholding his parents’ reputation while covering up their shortcomings. He would raise his parents’ stature and inherit the family’s royal surname.

Lately, many little things made Harmunik angry. It was as if everything was not where it should be, and that provoked her resentment. The pu tao leaves that the wind had blown to the ground bothered her. The loud voices of children returning from school annoyed her. Everything felt wrong. The main cause was Boneo, who had no plans to marry. He was like a mature tree that was reluctant to bear fruit.

“What’s wrong with you, Boneo? You have a steady job, you have enough money, and still you don’t want to marry,” Harmunik spoke in an agitated voice. It seemed her only child had no ears for her words or the neighbors’ gossip.

“I haven’t found the right one yet,” Boneo answered casually. “Even though marriage is the law of nature, it’s impossible to enforce.”

Boneo’s extended bachelorhood had provoked an unfavorable rumor that he was like the people in the story of Lot, who were struck by a meteor shower for being attracted to the same sex. How was it possible that an athletic, handsome man, with a good education (which had landed him a good position in his office), stayed single until he was in his forties? Something must have gone wrong in Boneo’s mind.

The rumor became disputable, however, when Boneo came home with a woman who had a smooth, creamy complexion. The neighbors — who were always eager to check out good news — smiled proudly.

If a well-established bachelor didn’t marry, it could only point to two facts: either he was mentally ill or steeped in immorality. It turned out that Boneo’s relationship with the fair-skinned woman did not last longer than a month. After that, Boneo walked alone again, smiling and without regrets.

“Your father must be crying in his grave, Boneo.”

“Why?”

“His lineage will end with you,” Harmunik said. “It’s pointless that your father planted this pu tao tree; now it’s a sign of your corrupt morals.”

“Is it immoral to be single?”

“What are you looking for? Knowledge? More money? Don’t you want to find a partner?” Harmunik snapped.

“I haven’t found the right one yet,” Boneo said to end the conversation.

Harmunik disputed all other reasons except for this one.

Boneo’s smile deepened the wrinkles around his eyes; and he started to leave.

Tears ran down Harmunik’s cheeks. Her howling sounded like a pair of crows proclaiming the demise of Boneo’s descendants.

***

Harmunik began to daydream frequently. She often rested her glazed eyes on the old pu tao tree. Ants had nested in the bark, and klarap (flying lizards) had bred in the tree’s hollow. She felt that a part of her heart had started to become hollow. The neighbors’ daily innuendos and gossip felt like large needles piercing through her chest.

“A family is like a tree. The older it gets, the denser its foliage becomes. More descendants,” Harmunik’s husband had said when planting the pu tao on the day Boneo’s placenta was buried. The tree was a symbol of the continuity of the family’s lineage. As long as the descendants are still alive, the tree must stay. Conversely, as long as it is still standing, procreation must continue.

The blood that had been spilled while giving birth to Boneo could not be removed. From the onset, Harmunik’s marriage was opposed by everyone. Harmunik, the daughter of a serabi kuah (Javanese rice pancake) vendor was fortunate to marry a man with a royal bloodline. Harmunik’s marriage went forward without her in-laws’ blessings, and, as a result, she was not allowed to use the family’s royal surname. She was an offshoot that had been deemed incompatible with the parent tree.

“That’s why I chose the pu tao,” Harmunik remembered her husband saying. “The pu tao may be worthless, but it is a prolific producer of plums.”

***

Just like Harmunik, who couldn’t hold back the aging process, the pu tao tree was getting older and losing its vigor. A strong wind broke some of its branches, and Harmunik’s yard was filled with broken, tangled branches and rotting leaves. Even though it was past the Duha praying time — around nine in the morning — Harmunik had no intention of cleaning up. She was waiting for Boneo to return from an out-of-town business trip. Harmunik was filled with turmoil; she felt as if she was pounding water in a mortar. After he returned from his business trip that afternoon, Boneo asked, “Mom, should I just cut down the pu tao tree?”

Harmunik remained silent.

“Mom, I promise I will marry someone next year. It’s just that I haven’t found the right one yet.”

“I don’t care; it’s up to you,” Harmunik did not feel like responding.

“All right, then I’ll cut down that old pu tao tree.”

Boneo sprung to his feet and went to fetch an ax. With a few strikes, he felled the pu tao. Boneo stripped the branches and cut them into pieces of equal size. He piled the wood on the edge of the porch. It could be used as firewood or charcoal to roast corn. Boneo wiped the sweat off his forehead and shoulders, then went inside to cool off.

Harmunik was still sitting silently in her chair. Her wedding photo lay on her lap. Her eyes were closed. A few moments earlier, when she heard the thud that the old tree made as it hit the ground, Harmunik had called the name of Allah repeatedly, in a weak voice.

The light of dusk broke through the window lattice and formed a pattern on Harmunik’s skin. The pu tao tree that used to shade the room was gone now.

“Mom, our house is brighter now. Nothing is blocking the sunlight,” said Boneo as he reached for a glass of cold water. “You know what, Mom? Yesterday I met with Amhar, a college friend, who’s also still single,” he went on, smiling. “Tomorrow, I will introduce Amhar to you,” he said.

“Mom, you better take a nap in the bedroom,” he went on, approaching Harmunik’s limp body.

Boneo approached Harmunik’s limp body.

The pu tao tree had been cut down, and Harmunik no longer worried about him.

***

Teguh Affandi is an award-winning short story writer whose works have appeared in Femina, Republika, and other publications. Translated from Bahasa Indonesia by Laura Harsoyo.

________________________________

We are looking for contemporary fiction between 1,500 and 2,000 words by established and new authors. Stories must be original and previously unpublished in English.

The email for submitting stories is: shortstory@thejakartapost.com

We are no longer accepting short story submissions for both online and print editions. New submissions to shortstory@thejakartapost.com will not be published.