Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsEntrusting fate of turtles to millennials

Sungai Belacan Beach is part of the 63-kilometer long Paloh Beach in Sambas regency, West Kalimantan. It is the longest beach for nesting sea turtles.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

I

n the mists of an early dawn on Oct. 7 at Sungai Belacan Beach, the waves rolled and crashed onto the shore. Prints of creatures are visible on the wet sand, from the shore up to the higher, greener areas.

Each spans about 90 centimeters, the width of a nesting sea turtle whose carapace is more than 1 meter in length.

Sungai Belacan Beach is part of the 63-kilometer long Paloh Beach in Sambas regency, West Kalimantan. It is the longest beach for nesting sea turtles, one of the oldest reptilians known to have existed almost 300 million years ago.

A camp and hatchery were established in the area in 2012, employing three enumerators who patrol the beach every night. They are busiest from May to October, as it is nesting season for sea turtles.

Aside from monitoring the nesting turtles, the enumerators are also assigned to take their eggs to the hatchery, saving them from seawater, predators or poachers.

“Please be patient, make no noise and don’t turn on the lights. Otherwise, the turtles are distracted, refrain from nesting and return to the ocean,” said Andi Priansyah, an enumerator who is escorting 19 youngsters to witness the event.

The youngsters are participants of Bujang Dare Penyu, which is part of Festival Pesisir Paloh (Paloh Coastal Festival) 2018.

Andi, is all ears. The sound of scraping sand signals that turtles are done nesting and have buried their eggs in the sand.

The finalists of Bujang Dare Penyu 2018 explore Sungai Belacan Beach in Paloh district, Sambas regency, West Kalimantan on Oct. 7. (JP/Severianus Endi)“Come on, you can see the turtles now. Be silent and keep the lights to a minimum,” said Andi.

A turtle came to our sight. It is a green turtle (Chelonia mydas), one of four species who regularly nests in the area.

Yuniarti, 18, a ninth grader at a state vocational school in the Paloh district, cries tears of joy. She embraces the turtle’s carapace of the turtle.

“This is my first time seeing a turtle. What a surprise,” said Yuniarti.

Andi reminds everyone to stay calm and to avoid pointing the lights in the turtle’s face, as it can become blind.

After the nesting is done, the turtles return to the ocean. The youngsters follow the slow-moving turtles while documenting the moment.

It takes two-and-a-half to three hours for a turtle to reach the beach, nest and return to the ocean. Following the ritual, enumerators would dig up the nest and take the eggs, around 120, to the hatchery. Within 40 to 50 days, the eggs hatch and the baby turtles are ready to be released into the ocean.

Yuniarti is the daughter of a fisherman. Her father told her that sometimes turtles get stuck in fishermen’s nets, but he always releases the turtles as he was aware of the turtles’ status as an endangered species.

“My father told me that if there are turtles stuck in the net, he will carefully lift them so that they would not stress out, and then my father would release the turtles back into the sea,” said Yuniarti.

Not all fishermen have the same awareness as Yuniarti’s father, unfortunately. Many are unaware that turtles may be on the brink of extinction.

An outdoor activity, which is part of the quarantine event for the finalists of the turtle ambassador program, was held at Sungai Belacan camp, West Kalimantan. (JP/Severianus Endi)“I am inspired by my father’s story, that is why I became member of nature lover group and spread awareness at schools,” said Yuniarti, adding that among her group’s activities are cleaning up the beach and participating in turtle monitoring.

Read also: Indonesia, home to six rare turtle species

Another story was told by Dono Rianto,19, a ninth grader from a fisheries vocational school in Pemangkat district.

When he was still unaware or the turtles’ status, he had to eat turtle eggs on a ship during a storm.

“I would like to make up for what I’ve done by spreading awareness at schools on the importance of protecting these animals. We conducted a long march along the beach, carrying sacks to collect plastic waste,” said Dono.

A small function hall at Sungai Belacan camp in West Kalimantan has walls made of used plastic bottles found on the nearby beach. (JP/Severianus Endi)The West Kalimantan program administrator of WWF Indonesia, Maria Theresia, believes that social media savvy millennials’ involvement in the program is important to ensure the delivery of messages about conservation.

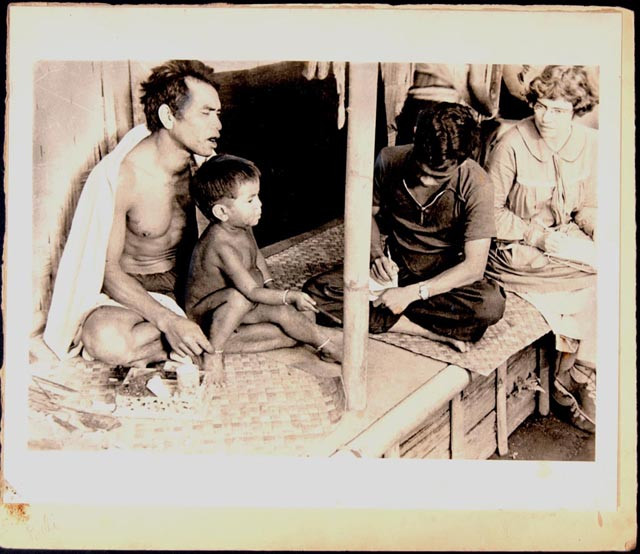

West Kalimantan Program Administrator of WWF Indonesia, Maria Theresia (center) gives a presentation on nature conservation to the 19 finalists of Bujang Dare Penyu on Oct. 6 at Sungai Belacan camp, West Kalimantan. (JP/Severianus Endi)“Their backgrounds are pretty promising. Many of them are activists of students’ organization (OSIS) at school and members of nature lover groups. They conduct activities independently, and this gives us hope,” said Theresia.

Challenges still exist, nevertheless. Some participants did not get permission from their families to take part in the event, because apparently the families are still linked to hunting and selling turtle eggs.