Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsShort Story: Mariana

I don’t know how Mariana, my classmate, could have sat still when the entire classroom bullied her.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

I

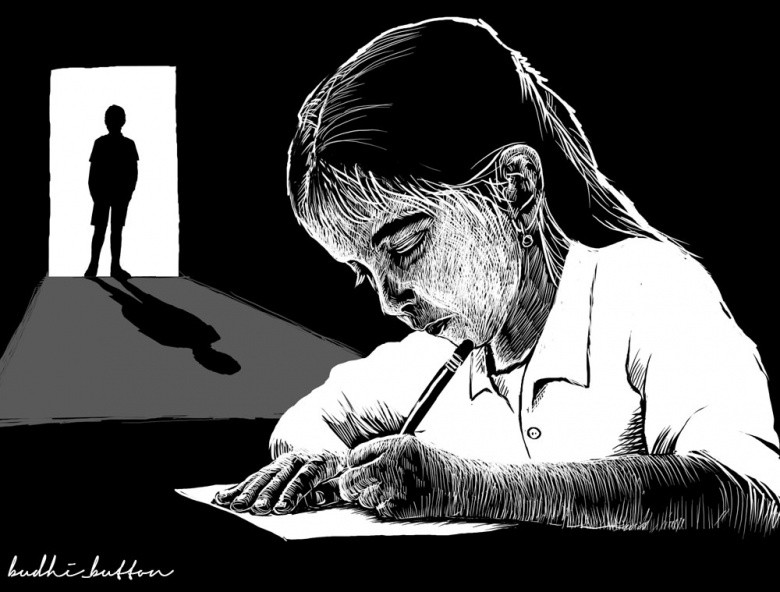

don’t know how Mariana, my classmate, could have sat still when the entire classroom bullied her. She stood still when Lan, a polio-ridden boy, hit her upper arm seven times — I counted. Because I sat two rows behind her, each blow felt like it had been aimed at me too. I cringed, while rubbing my own upper arm, somehow sharing her pain.

The teacher had been absent during that particular period, so everyone in my classroom was busy teasing each other. The subject of that day’s tease was Lan. He was said to be in a relationship with Keti Clara. Upon hearing this Lan threw a rage and asked: “Who told you that?” As a joke, nearly everyone pointed at Mariana, who kept her head down and who seemed preoccupied with her own writing. She was finishing a story titled “A Sad Tiger in the Forest” — or so I assumed, because several times during recess I had caught her scribbling in a notebook, and at the top of the page was the title of the story. It upset me that Mariana would not stand up for herself. Why didn’t she tell the classroom it wasn’t her who started the rumor about Lan and Keti Clara? Why would she let everyone play a joke on her like that? Her silence aggravated me. There was another time when Keti Clara — the daughter of our PE teacher — said, “Hey, Mariana, why don’t you write a story titled ‘The School Janitor’?” and the classroom erupted in a mocking laugh. Still, Mariana kept her mouth shut. My ears burned at each comment thrown by our classmates; and I felt like I should have stood up for her, but I was afraid they would assume I had feelings for her.

Mariana’s father was the custodian of our elementary school on Kalipokan Island. My father worked at the same school teaching Bahasa Indonesia. We came from Donggala, but my father accepted the offer to be stationed on Kalipokan Island, so we all moved there and lived in a residence provided by the government. Mariana’s family also lived in the same complex, but the house she lived in was old and in need of significant repairs while the house my family lived in had recently been renovated. All the teachers who were not native to the island lived in these new homes, and you could easily spot them because their walls were painted bright green. Mariana’s home stood out because it looked dilapidated compared to the other houses in the complex. She couldn’t even use the restroom in her house to defecate. So, every morning at five I would look out the window and find her walking down the road with an oil lamp in her hand, heading for the school to use the public toilet at our school.

One day, while I was rinsing and feeding my pet turtles on the terrace, I caught Mariana raising the national flag in the school yard and unlocking each classroom door. She would also unlock the teacher’s lounge and sweep every inch of the room, before mopping the terrace outside the lounge to clear away the dirt. She had been doing this for a week because it was the dry season and dust is a common issue during this particular season. After Mariana had completed her tasks, she would return home to shower before coming back to school. The distance from our classroom — the fifth graders’ classroom — from my house was approximately 53 steps, and it would take another 39 steps to go from my house to Mariana’s house. I calculated the distance quietly one Sunday morning when no one was around. Other teachers and their families were off having a picnic; and Mariana’s family had got on a boat to visit Padal Island. When they returned from the visit, Mariana’s mother brought my family a basket of sea slugs, which my mother happily turned into a delicious dish infused with coconut milk.

I never talked to Mariana, not because I didn’t want to be friends with her, but because we were not of the same gender, and I wouldn’t feel right going up to her and asking her why she had been taking over her father’s work at school. One evening, while my mother was helping me finish my homework, I asked my mother the question that had been nagging at me for some time. She said perhaps Mariana was simply helping to ease her father’s burden; she also explained to me how Mariana’s father was taking on several jobs to make ends meet. He not only worked as the school custodian; he also worked as a farmer and a fisherman. My mother often bought fish from Mariana’s father — and it was Mariana’s task, as well as her sister’s, to sell their father’s catch. The two sisters would go around the village with a shoulder yoke full of fish, hoping to sell them to the villagers. They would do this in the evening, or in the afternoon. There were moments when I really wished I could spend time with Mariana and take her to the beach or to the forest on the outskirts of the village, looking for wild passion fruit. But it was only in my mind. I didn’t have the guts to ask her to play with me; besides, I don’t think she had the time.

Out of all the school subjects we had to study, only math and PE would land Mariana in trouble. Personally, I couldn’t care less about PE lessons, or Bahasa Indonesia, or social sciences; however, I loved math — even though I wasn’t crazy about our math teacher. I didn’t like our Bahasa Indonesia lessons, either; but because my father taught the subject, I had no choice other than to pretend as though I loved it. When my Bahasa Indonesia score fell to an average level, my father would say, “Look at Mariana. She always aces her homework and exams. Why don’t you study with her?” It was a question I had never attempted to answer.

Still, Mariana’s achievements in my father’s class didn’t extend to our math class. Somehow, she always received a punishment from our teacher. Sometimes, the punishment was for her to crawl under the chairs; other times, she would get her ear tweaked by our classmates. This was Encik Nayi Tanse’s rules: she would ask a student to solve a problem on the blackboard, and if the student couldn’t solve it, she would call on another student to solve it. If the second student got it right, she would ask that student to tweak the ear of the student who got it wrong the first time. Nearly half of our classmates had tweaked Mariana’s ear during math class. Encik Nayi Tanse often asked me to do the same when I happened to get the solution right after Mariana’s failed attempt to solve the problem on the board, but I didn’t have the heart — so I would simply touch her ear lightly and fake-tweak it. I didn’t like Encik Nayi Tanse because she always gave us punishments that I thought were strange and senseless, such as hitting the wall a hundred times, or dabbing chalk powder on each other — and if the powder got into your eyes, it stung. Pipi Nari once suffered from itchy skin after she was dabbed with chalk powder. On the back of my math notebook, I scrambled the teacher’s last name from “Tanse” to “Setan”, which means “the devil”.

One Wednesday in 1997, a photographer came to our school to take our headshots, for which our parents had to pay around Rp 3,500 each. The sessions were held for fifth and sixth graders only; and Encik Imani Asnum — our PE teacher — Keti Clara’s mother, called us into the teachers’ lounge one by one. Once inside the lounge, we were asked to stand in front of a solid blue backdrop stretched from one end of the room to another, before the photographer took our picture. When it was the fifth graders’ turn to join the session, Mariana’s sister was absent. Although she was called to attend the session repeatedly, Mariana’s sister refused to leave her seat. Unable to persuade Mariana’s sister to join the photo session, Keti Clara’s mother stood in the doorway of the teacher’s lounge and shouted at the custodian: “Hey, your daughter refuses to be photographed. Perhaps we should withhold her report card, as well — and her graduation certificate — so she’ll follow in your footsteps when she grows up!”

Hearing this, Mariana’s father rushed toward the school storeroom and grabbed a large bamboo pole often used to water the plants. Then he entered the fifth graders’ classroom and dragged Mariana’s sister by the arm, taking her out into the yard where everyone could see what came next. Swinging the bamboo stick repeatedly in the air, Mariana’s father struck his daughter’s head, back and hips without mercy. Mariana wailed in tears — it was the first time I had seen her cry for help, begging for someone, anyone, to separate her father from her sister. Yet, as expected, no one came to the rescue. Everyone simply watched the entire event unfold as if it were a circus show.

I ran into the teachers’ lounge, searching for my father, but he wasn’t there — so I rushed back home to look for him, yet Mother told me he was performing his midday prayers. I grew anxious: it seemed to me as though my father took forever to pray.

By the time I went back to the school, Mariana and her mother were doing everything they could to protect the little girl from further beatings. They used their own bodies as shields against the blows. A little while later, my father came from his midday prayers, along with my mother. He wrapped his arms around Mariana’s father’s body and used all the strength he had to pull him away from the poor girl. My mother helped Mariana’s mother carry the little girl inside the classroom, where they washed and cleaned her body. In the evening, I accidentally overheard the conversation between my parents about what happened that afternoon.

“The custodian hit that child until she wet and soiled her pants,” said my mother. “It’s not that she didn’t want her picture taken by the photographer, but she was embarrassed.”

“Why was she embarrassed?” my father asked quietly.

“She was having her first period,” said my mother. “And it leaked through her skirt.”

I wondered what it meant to have a period.

The next day, Mother spotted Mariana seated under a ketapang tree behind the house where her family lived. She was all alone. Mother asked me to bring her a bowl of diced papayas. Because the roads were clear and there didn’t seem to be anyone around, I summoned my own courage to approach her.

“My mother asked me to give you this,” I said.

“Thanks,” said Mariana, accepting the bowl of diced papayas.

“Mariana, what does it mean to have a period?”

She turned to me, “It’s bleeding that all women receive each month.” I nodded, as if I understood what that meant. Even though my head was now filled with more questions than anything else: why would blood come each month? Does it come from the mouth or ears? However, I didn’t want her to think of me as a stupid boy, so I didn’t ask these questions.

“I’m not angry at my father, but I hate what he does,” said Mariana. “My grandmother used to beat him, too, when he was little. My father had to learn how to take care of himself from when he was seven years old. He’d work odd jobs to make ends meet—draw water from a well to fill the bathtubs in other people’s homes; climb coconut trees and pick their fruit; as well as repair fishermen’s boats. One day, when he was 15, my father fell from a coconut tree and hit his head against a rock. Ever since then, he has always struggled to control his anger. He takes medicines for it, to calm himself down. My mother told us all this.”

It was the first time Mariana had spoken more than a few sentences to anyone.

I don’t know what sort of books she had read that would allow her the space and discipline to talk in this way, or to write a story called “A Sad Tiger in the Forest” at the age of 12. However, as in any story, time also passed in this story, our story, and the next thing we knew we were graduating from elementary school. Everyone in our class graduated to junior high school, except Lan. My father was reassigned to a different island, Togean Island, which was an eight-hour boat ride and a five-hour car ride from Mariana’s village. Mother said Kalipokan Island wasn’t the best place for us to live in as a family; and not the best place for me to grow up in.

After that period, I lost all contact with Mariana.

***

Erni Aladjai is an Indonesian writer born and raised in the Banggai Islands, Central Sulawesi. She runs Bois Pustaka, a chapter of Pustaka Bergerak Indonesia, in her village.

______________________________________________

We are looking for contemporary fiction between 1,500 and 2,000 words by established and new authors. Stories must be original and previously unpublished in English.

The email for submitting stories is: shortstory@thejakartapost.com