Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

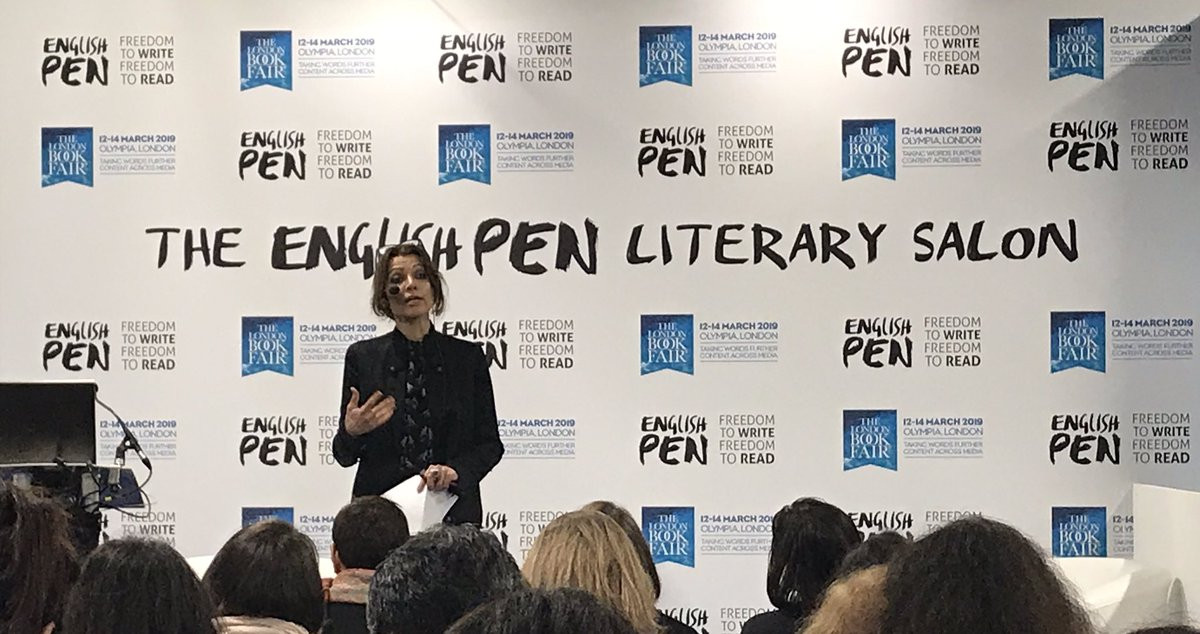

View all search results‘Extremists polarize humanity, storytellers do exact opposite’: Elif Shafak

The Jakarta Post talked to Elif Shafak on the sidelines of the London Book Fair, discussing politics and literature, gender discrimination in the publishing industry and Rumi.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

Elif Shafak has ticked all the boxes that make a writer a writer.

She has penned 17 books, in both English and Turkish, won numerous awards for her works and gained recognition as a person “who would make the world better” by Politico in 2017. She actively speaks out against persecution and oppression by authoritarian governments and, being a female, faces gender-based discrimination.

Shafak was at the London Book Fair for the launch of the International Literature Showcase (#LitShowcase) – a two-year partnership between the National Center for Writing and the British Council supported by the Arts Council England.

The Jakarta Post talked to Shafak about politics and literature, gender discrimination in the publishing industry and Rumi.

You talked about how identity politics affected the way stories were read, especially those written by non-Western authors. Have things changed?

The world we are living in today is deeply divided, polarized and shaped by tribalism. Art and literature need to move beyond political tribes. Beyond “information ghettoes” or “cultural islands”. Storytellers connect people and cultures across borders. To me, it is very important that writers refuse to be pigeonholed down into narrow identity politics. I do not have a single, monolithic identity. Instead, I have multiple belongings.

Your books and their readers are highly diverse. You said in the same talk about identity politics that a writer should be free to write beyond their own identity. How do you write beyond your own cultural identity without falling into the trap of cultural appropriation? What about political correctness?

I believe as human beings we all embody “multiplicity” inside. We have many layers, many sides. Literature is not always about telling your personal story to the world. Sometimes it is like that and I respect this.

But what excites me much more than “telling my autobiographical story” is understanding, feeling, hearing “the other”. For me, one of the most powerful aspects of literature is about transcending the boundaries of identity politics. In my books there is a consistent desire to bring the periphery to the center, to make the invisible more visible, to give more voice to the silenced.

This is why I am not only interested in stories, I am also interested in silences. I question taboos. I question the things we find difficult to talk about. All extremist ideologies polarize humanity and they “dehumanize” the "other", but a storyteller does the exact opposite: Stories rehumanize those who have been dehumanized. For a storyteller there is no “us” versus ‘them”. There is only human beings — East and West, we are all deeply connected.

Read also: 'London welcomes Indonesia': 2019 London Book Fair marks 70 years of Indonesia-UK bilateral relations

Do you think a writer must always be political? Or is it just inevitable?

If you happen to be a writer from a “wounded democracy”, such as Turkey, Egypt, Pakistan, Venezuela -- and the list of such countries is sadly getting longer -- you do not have the luxury of being apolitical. There is always a political edge to my writing. However, I do not like it when writers preach or try to teach. A writer’s job is not to give the answers, but only to ask the questions. In my books, I ask questions and I always leave the answers to the readers because every reader is different and unique and they will come up with their own answers. I respect that.

You faced criticism for writing in English since it is not your mother tongue. What do you think about this? What keeps you going?

I am very critical of ultranationalism and I am very critical of any ideology that divides human beings into antagonistic camps.

I do not think along nationalistic lines or tribalistic lines. Why can’t a poet or a novelist write in more than one language? Who decides? If we can dream in more than one language why shouldn’t we be able to write in more than one language?

For so many years now I have commuted between Turkish and English, just like I commute between cultures, between East and West. If there is sorrow, melancholy, longing in my writing I find it easier to express these in Turkish. When it comes to humor, irony, satire, I find it much easier to express them in English. So I feel attached to each language in a different way.

It is intriguing that you are one of the most widely read writers in Turkey and yet in my country Indonesia your works are hardly known. What are your thoughts about this?

I’d love my novels to reach readers, storytellers and book lovers in Indonesia. That’d make me happy. I am always intrigued by Indonesia’s history, culture and society. I find lots of similarities as a Turkish writer and I follow the debates in Indonesia about identity, faith, women’s rights and public space. There are so many overlapping themes. So it’s a country that’s close to my heart and I hope through stories and storytelling we can connect better.

As elsewhere, women in the publishing industry face discrimination and prejudice because of their gender. What is your experience? What is the most striking discrimination that you have personally faced? How do you fight against gender inequality as a writer?

The publishing industry looks “modern” and “very open-minded” at first glance. However, underneath it can be quite patriarchal. There is a big gap between the number of reviews for women writers and the number of reviews for male writers. The industry treats women differently, but it’s very subtle and we need to talk about it.

But I have faced so much discrimination in Turkey as a woman writer for so many years. In my motherland a male novelist is primarily a novelist. No one talks about his gender. But a female novelist is primarily a woman and then a writer. So you are treated differently from the very beginning. The elite are mostly conservative men and I was always belittled, looked down upon and slandered by many conservative and nationalist male elite. But what keeps me going is my love for the art of storytelling and the readers. Book readers are amazing! In countries where there is no freedom of speech perhaps books matter even more and when a reader likes a novel she shares it with her friends, with her aunt, with her sister-in-law. To me that is very precious. If books survive and thrive it is thanks to the love of their readers.

A must-ask question: Why Rumi?

Rumi has a special place in my heart -- ever since my youth, my university years. Also, Shams. I am interested in mysticism in general. I like mystical philosophy and I love reading mystical poetry. My work and my world combine Eastern and Western sources of knowledge and understanding. I also want to bridge oral culture and written culture. That, too, matters to me. (kes)