Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

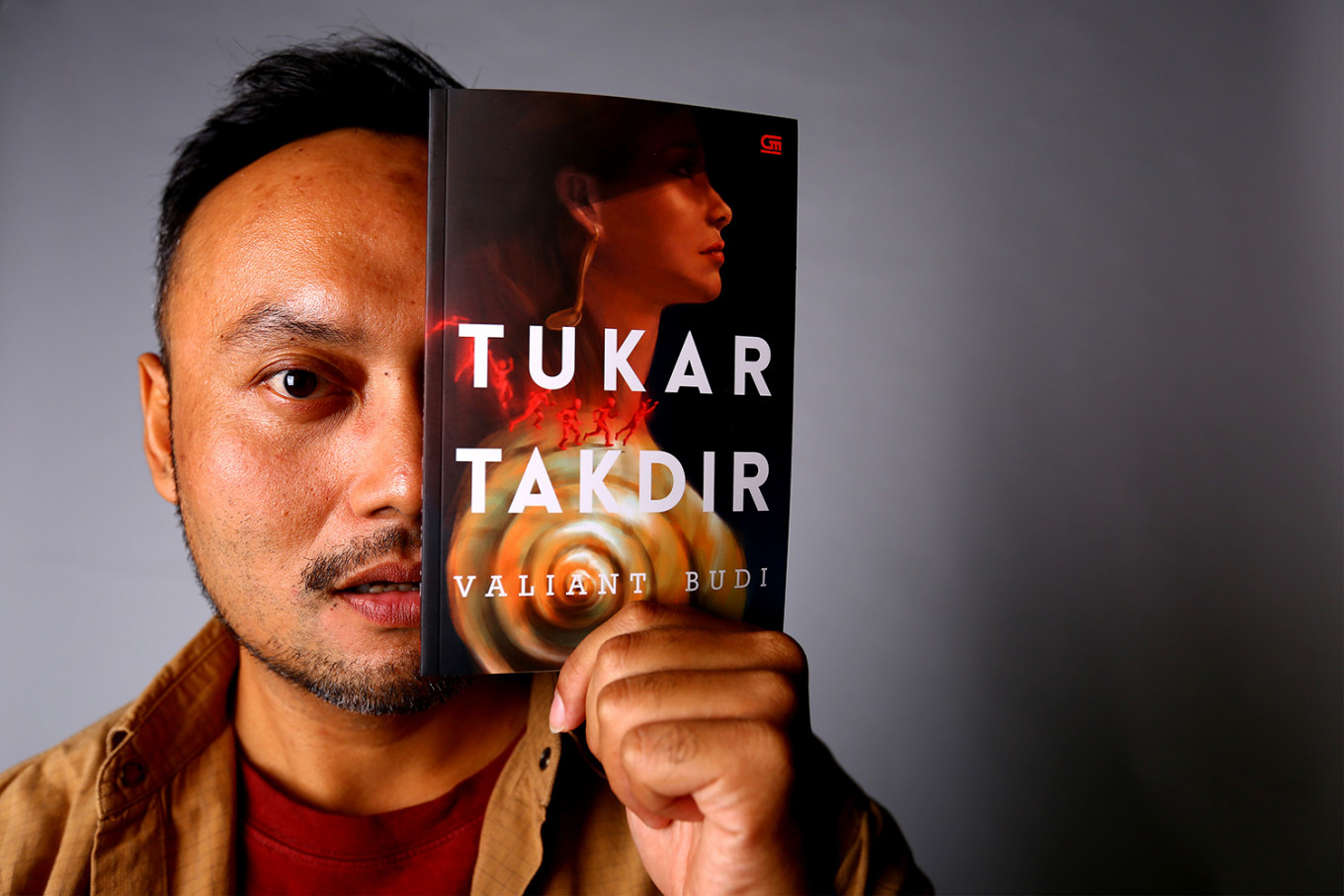

View all search resultsA twist of fate: Valiant Budi on 'Tukar Takdir', writing and life

Valiant “Vabyo” Budi Yogi plays with the idea of fate and humans in his latest book Tukar Takdir (Changing Fate).

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

W

hat is fate? What is it like to be in a doomed airplane before it crashes? Also, what is the similarity between an actor and a luwak (civet cat)?

Valiant “Vabyo” Budi Yogi plays with the idea of fate and humans in his latest book Tukar Takdir (Changing Fate). Launched last Friday, the book explores the inevitability of fate and the unexpected turn our actions can produce.

“There are two different definitions of fate, at least according to the Great Dictionary of the Indonesian Language [KBBI] and Wikipedia. According to the KBBI, fate is inevitable, while according to Wikipedia, fate depends on our actions,” Vabyo told The Jakarta Post during a visit on Thursday. “I like the latter definition better because it means that as humans, we still have the authority to decide our own life and fate.”

The concept of Tukar Takdir had been in the works since late 2015. However, the stories in the book could be traced back further than that. One story owes its origin to a draft of an unfinished novel that had existed since 2013 but was forgotten for a while.

“Now, I plan my stories ahead. Since suffering from a stroke, I’ve lived with cognitive problems that often make me forget about things,” he said. “Even while writing, the story might end up differently, without planning. I get lost in my own mind.”

A collection of 12 short stories, Tukar Takdir was written through the perspective of multiple narrators. One of the challenges Vabyo found in writing was how to stay true to the character and not to drown in himself.

“There are times when I have difficulties, when the character is too Valiant and not Mardikun, for instance,” he said. “When I’ve become comfortable with one character, comes the next challenge: To move on to the next one when starting another story.”

Read also: 12 Indonesian books you should add to your reading list

A common mistake in books that employ multiple narrators is when the author fails to craft distinguished voices for each one. Instead of richness, the book will feel dry. To avoid falling into this trap, Vabyo made a scheme for the characters. Small details, including language and vernacular, matter – especially when his cast of characters are highly diverse, ranging from a Sundanese man and a snail to a Betawi woman.

“There is this stall in Ubud [Bali] owned by a Betawi emak-emak [old lady]; she became the inspiration for my character. The original is much cruder than the fictional one,” Vabyo said.

This Betawi woman in Ubud is the only Betawi person he knows in real life, despite the fact that he lived in Jakarta for years before moving to Bali.

Of course, there is also a story that is based on Ubud, but in Vabyo’s version, gone is the romantic, soul-healing version of Ubud that has become a mecca for soul-searching tourists after Elizabeth Gilbert’s Eat, Pray, Love. Ubud in Vabyo’s world is a haunted place, both by ghost and memories.

One of his characters said it best: “I’ve seen many come here for romance, only to go home with a broken heart instead.”

This is one of the many jabs at the reality that Vabyo has included in his stories. He conceded that he could speak the truth better through fiction and humor.

The latter has become a key characteristic of his works. His first book, Kedai 1001 Mimpi (A Cafe of 1001 Dreams), which tells his story while working abroad as a barista in Saudi Arabia, is also rife with humor.

“There was a lot of pressure in my life back then, and humor became my source of strength. I was stressed and dramatizing the situation would worsen the pain. Through humor, there was something to laugh about,” he said.

Tukar Takdir was born out of a similar hardship, hence the humor.

“I learned about humor from Hergé, the author of The Adventures of Tintin,” he said, citing his influence, which also includes Enid Blyton and Alfred Hitchcock.

While he learned about the sense of youth and friendship from Blyton, he was greatly inspired by Hitchcock in writing his stories. It is no wonder that his readers start his stories with the expectation of a plot twist – which he discouraged.

“For the readers: Don’t go in hoping for a plot twist. Expectations can kill you,” he cautioned. “I never force a plot twist just for the sake of a plot twist. It’s automatic.”

Plot twist or not, one thing is sure: writing is fate.

“It’s a fate that I get to choose.” (wng)