Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsTackling HIV stigma amid LGBT+ ‘moral panic’

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

A

head of World AIDS day, Indonesian LGBT+ rights activists warn that escalating “moral panic” is discouraging vulnerable populations from accessing HIV prevention and treatment.

For HIV-positive activist Acep Gates, the increasing discrimination in his hometown, Cianjur in West Java, has forced him to go to Jakarta each month to get treatment. In Cianjur, the local government distributed warnings to schools and mosques about the “dangers of LGBT+”, one of the dangers listed was HIV.

This deterred Acep from seeking healthcare in his town. He was only tested when he noticed he had similar symptoms to what he had read about HIV online.

“I think most people in Indonesia who are HIV positive try to hide their status because of stigma and discrimination,” he said.

HIV, the virus which leads to AIDS, is now treatable and preventable for those who get advice early enough. In wealthier countries, an HIV diagnosis does not affect average life expectancy.

In Indonesia, there are barriers to preventing and treating HIV. It is one of the few countries that has seen an increase in new cases of HIV in the last few years.

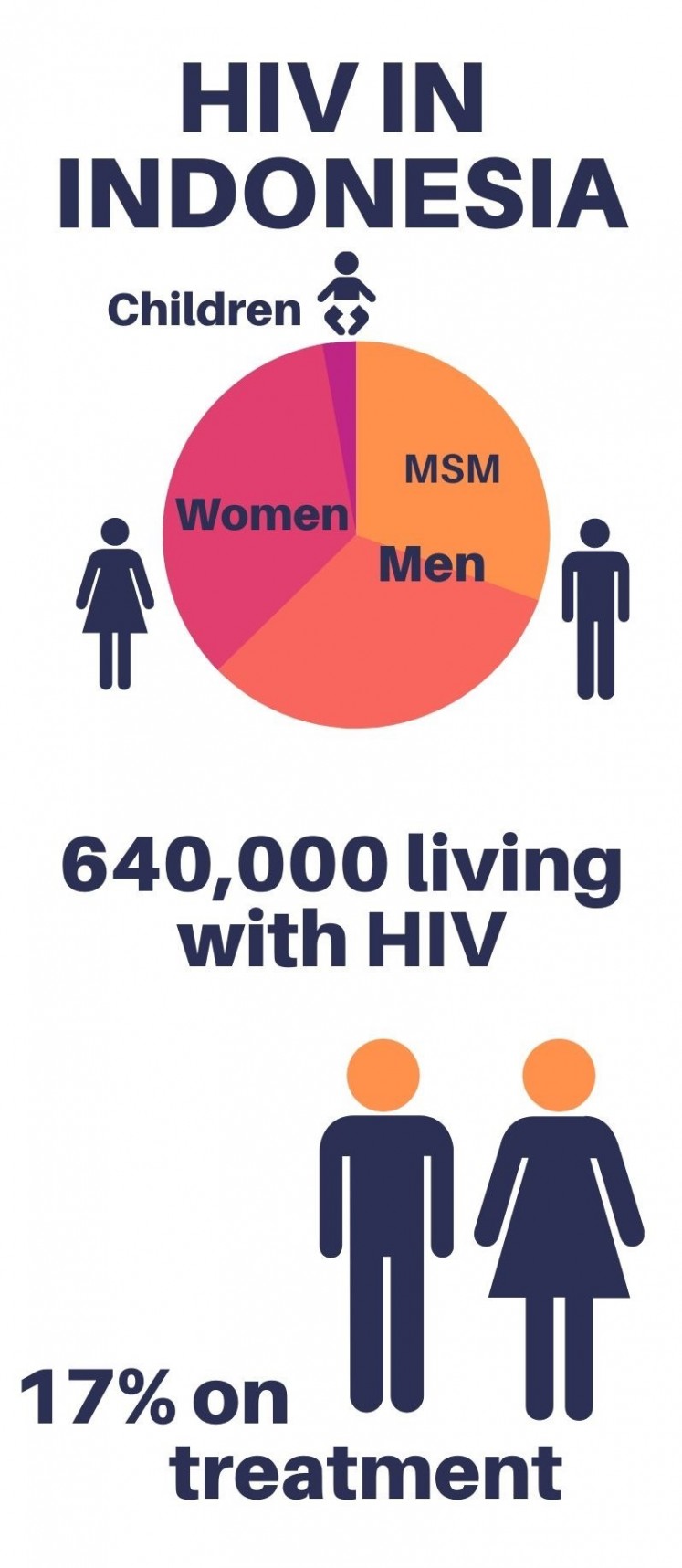

This infographic shows the gender, sexuality and treatment breakdown of people living with HIV in Indonesia. (UNAIDS/-)A 2018 United Nations report found that 25.8 per cent of Indonesian men who have sex with men (MSM) had HIV, up from 8.5 per cent in 2011. It also found that 24.8 per cent of Indonesian transgender people had HIV.

The higher number of cases of HIV in the queer community has fueled stereotypes about LGBT+ people.

With increasing religious fundamentalism, negative perceptions of LGBT+ people are increasing, said Dede Oetomo, LGBT+ rights activist for GAYa Nusantara.

“Indonesian society has become more and more polarized now. People [....] cannot tolerate other people who are different from them,” he said.

Likewise, Amahl S. Azwar, an HIV positive blogger and writer, often sees intolerance spread online.

“[Some Indonesians] have already made up their mind; if you’re LGBT+ – if you’re queer – then you’re HIV positive because that’s what you deserve, basically,” Amahl said.

Religious attitudes also block public discourse about sexual issues, said Ignatius Praptoraharjo, Senior Researcher at the AIDS Research Centre at Atma Jaya Catholic University. This produces a vicious cycle: the more queer people are driven underground, the more likely they are to contract HIV.

A display of Antiretroviral (ARV) medicine (AFP/Adek Berry)“This is the trend that will make sexuality more hidden [….] and restrict the government from ensuring prevention measures are available [….] We are focusing on providing services without considering how people can access them freely, without fear, without stigma and without discrimination,” Ignatius said.

Limits on accessing HIV prevention have worsened since raids on LGBT+ social venues in 2017, according to Dede.

An example is the Criminal Offences Draft Bill, which would make it a crime for HIV outreach workers to distribute boxes of condoms to at-risk communities.

Another prevention measure, PrEP, Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis, a medication that can prevent people at risk of HIV from being infected, is not widely available. Although the Indonesian government committed to a PrEP pilot program in June, there has been little progress since then.

Some clinics import PrEP from abroad at the patient’s request, and it can be bought online, but this is expensive, and the amount is restricted. Due to the risk of gay men being prosecuted for having sex with other men, PrEP suppliers are hesitant to provide the medication because it could jeopardize the well-being of those they are trying to help.

Despite policy researchers advocating for PrEP to be made more accessible, it is strongly associated with men who have sex with men (MSM), so the government is reluctant to even discuss it, Praptoraharjo said.

Amahl agreed.

“How are you supposed to talk about PrEP when the very idea of sex outside of marriage and non-heterosexual sexual relations is so frowned upon?” Amahl said.

While the LGBT+ community is stifled and access to HIV health care limited, queer people are attempting to tackle stigma by strengthening their online community.

Acep uses YouTube and Instagram to dispel misconceptions and educate people about HIV issues.

“I think social media is one of the best ways to promote awareness of HIV because it’s easier for people to find information.”

That is powerful because millennials have a higher risk of contracting HIV, and the internet is their primary source of information.

Social media has become an essential platform for HIV education. It allows LGBT+ people to remain anonymous, meaning they don’t have to “come out” to get advice.

Sharing personal stories can also be very empowering to LGBT+ and HIV positive individuals, Amahl said.

“The more I talk about it – the more I try to help people realize I’m ok – the more I’m helping myself as well,”

Grace Desoe and Shelley Cheng traveled to Indonesia with the support of the Australian Government’s New Colombo Plan Mobility Scheme.