Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsNot our fate: Researcher unearths roots of racism against Chinese-Indonesians

Writer and researcher Widjajanti W. Dharmowijono looks into her country's history to understand racial tensions.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

D

uring the May 1998 riots and mass rape, Widjajanti “Inge” W. Dharmowijono received an urgent phone call from her colleague.

Inge was informed that a crowd – primarily demonstrators protesting the rule of then-president Soeharto – was already roaming the streets near her home.

"My colleague told me to beware," Inge recalled in a Zoom interview with The Jakarta Post on Wednesday (07/04). At the time, Inge, now 73 years old, was a lecturer and the head of the Dutch Department at Akademi Bahasa 17 Agustus 1945 in Semarang.

Inge looked out of her windows. No protestors. The usually busy street looked eerily deserted.

"Our house was located near the city center," she said. "Groups of protesters usually passed by our house, yelling and shouting their demands. Day by day, they were becoming more and more violent."

Inge had another reason to be afraid. A few weeks prior, she had received a bone-chilling email.

"I didn't recognize the sender of the email," the linguist said, "but the content was scary."

According to Inge, the email's anonymous sender wrote that they would rape all Chinese women and "destroy their [private parts]", so that they will never again bear children.

"We're no cowards, but we decided to get prepared," the mother of three said.

"The May '98 tragedy truly gripped me," the former lecturer said. "[Since then], I have looked into a lot of articles and books discussing the incidents, trying to understand what had happened."

She learned from an article by renowned economist Kwik Kian Gie that conflicts between Chinese-Indonesians and indigenous locals were a legacy of the Dutch colonial era. Inge also learned that, according to some, the racial hatred stemmed from the perception that Chinese-Indonesians took the Dutch's side during the colonial period.

Inge wanted to know how Chinese Indonesians were presented in the texts written during the colonial era and researched colonial-era Dutch documents and literary works for her doctoral study at the Universiteit van Amsterdam in 2004.

Over five years, Inge studied more than 200 official documents, dissertations, magazines, novels, poetry and travel journals produced by the Dutch government between 1880 and 1950 that are kept within the archives of the Universitaire Bibliotheek Leiden, Koninklijk Instituut voor Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde (KITLV) and Koninklijke Bibliotheek Den Haag.

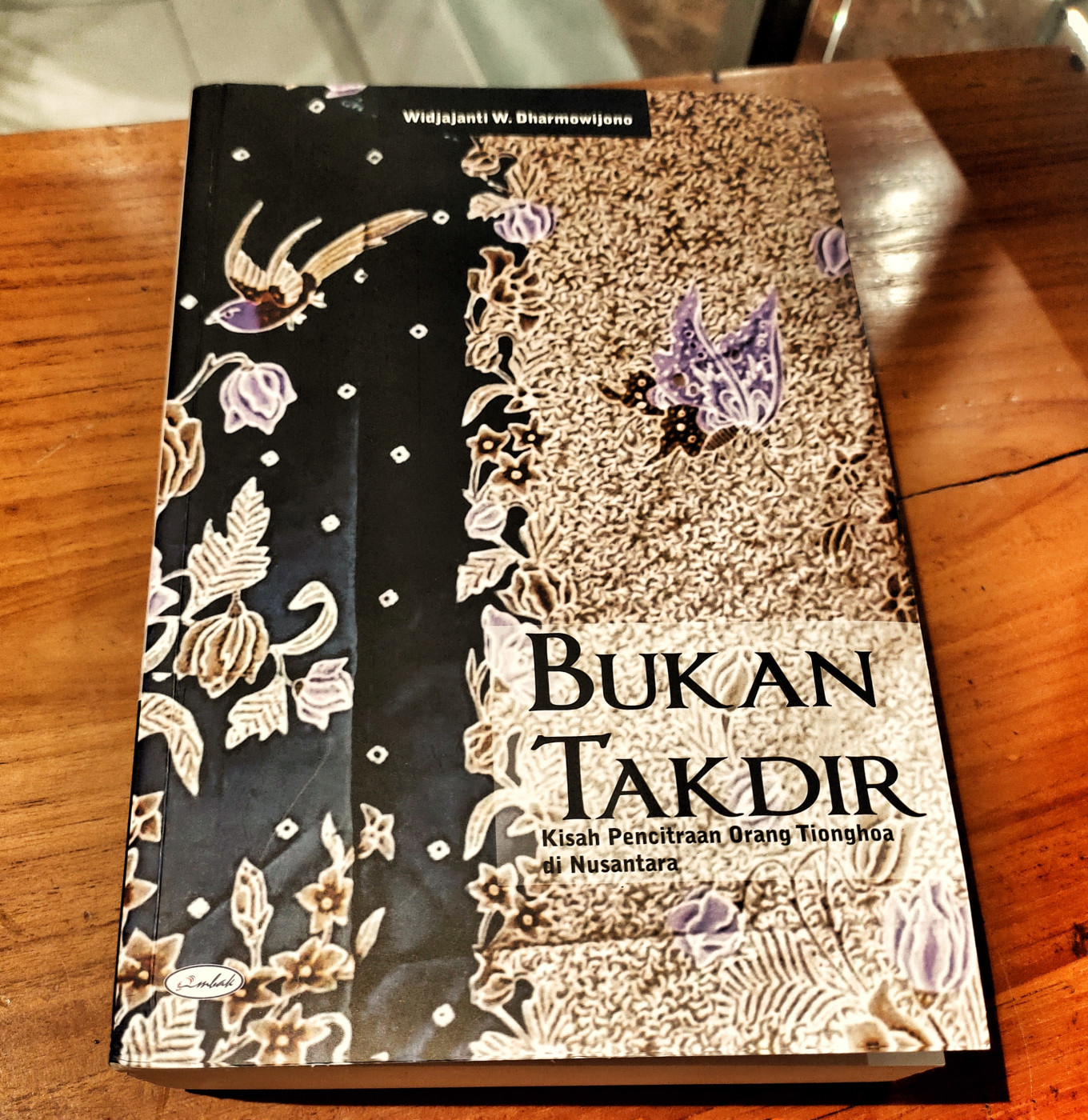

After graduating, Inge translated her dissertation into Indonesian. She published it as a book titled Bukan Takdir: Kisah Pencitraan Orang Tionghoa di Nusantara (Not Fate: The story of Chinese-Indonesian's image in Indonesia).

"Fate is something given that we cannot avoid, while prejudice and hate crimes against Chinese-Indonesians are not fate but the result of stereotyping and stigmatization during the colonial era," Inge said.

Published by Penerbit Ombak, the 663-page book offers factual records and excerpts of documents and literary works written by Dutch officials, historians and authors regarding Chinese-Indonesians.

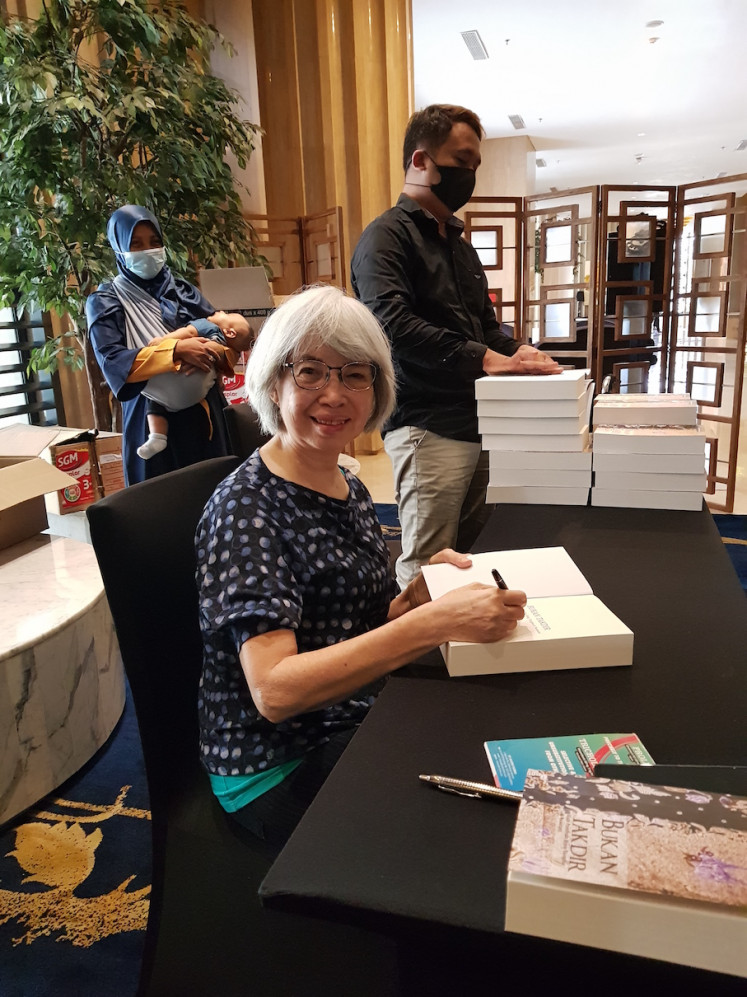

"It's an important and impressive study on the history of the Chinese in Indonesia, especially in the colonial times," professor emeritus Bert Paasman, a retired professor at Universiteit van Amsterdam and Inge's mentor during her doctoral study, said during the book launch on Zoom on Monday (05/04).

Feared and Needed

Inge's book reveals that, while it is not known when exactly the Chinese first came to Indonesia, historical records show that Chinese had lived among Indonesia's indigenous people since the 7th century, long before the Dutch arrived. Most were traders, escaping wars, natural disasters and famine in their own country.

At the time, women were forbidden to emigrate out of China, meaning that most of the first Chinese immigrants were men. They married local women, bore children and decided to stay in the archipelago.

When the Vereenigde Oost-Indische Compagnie (VOC) established its headquarters in the archipelago in the early 1600s, they invited more Chinese workers to help build cities and infrastructure.

Thousands of these immigrants were tricked into working in slave-like conditions at plantations and mines in Java and Kalimantan. They suffered from dire malnutrition. Many tried to escape and were flogged to death, while others died of beriberi, cholera and other diseases.

The Dutch believed that these Chinese workers deserved such treatment because they were already outcasts of their own country.

"In racism and other forms of discrimination, stereotypes are dominant," Paasman said. "Generalization of stereotypes often leads to animosity and hatred, and the results are dominance, exploitation, forced labor and slavery."

On the other hand, well-to-do people of Chinese descent in the cities were often visualized and described as snakes, hyenas or vultures in Dutch novels and travel journals. They were pictured as cunning and conniving. Their shops, for example, offered more varied merchandise at lower prices. Some believed that they could afford to do so because they obtained goods through illegal means.

"The Chinese were both feared and needed at that time," Inge said. "In any business, they always provided better and faster services at lower prices. They became tough competition for the Dutch."

Rumors circulated among the Dutch that the Chinese were plotting to overthrow and drive them away from the archipelago. In an attempt to control the growing Chinese population, the Dutch put heavy taxes on each of them and their belongings. The Dutch elected a "captain" from among the wealthy and well-connected Chinese families to make sure everybody paid.

The taxes grew and were exacted on every Chinese-Indonesian, regardless of economic standing, Inge explained in her book. Many poor went into hiding to evade tax collectors, but the Dutch organized raids to hunt them. Those captured were heavily punished and jailed.

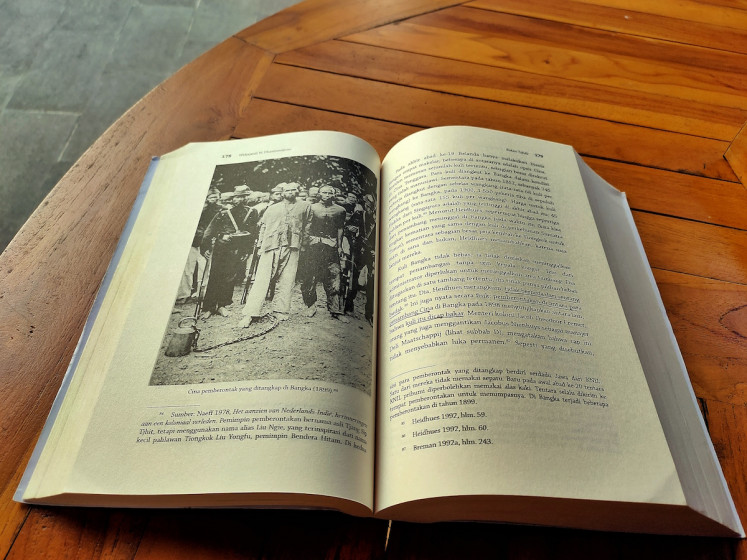

This situation resulted in the 1740 Batavia massacre against the Chinesein Ommelanden (now Tangerang and Bogor) instigated by Dutch soldiers alongside collaborating locals. This event is sometimes known as geger pacinan, resulting in the death of approximately 10,000 Chinese men, women and children.

The Dutch promised large sums of money to those that beheaded Chinese rebels. The colonial government also sent letters to sultans in Cirebon and ordered them to arm thousands of men and send them to Batavia.

Divide et impera

In the following years, the rules imposed by the Dutch on the Chinese became stricter. People of Chinese descent had to wear traditional Chinese attire, which included a pigtail for men.

Under the Wijkenstelsel rule, they were only allowed to build houses and live in the designated Pecinan (China Town). For every travel outside the Pecinan, they were required to have a permit that was hard to obtain.

Interracial marriages were strictly forbidden. "The Dutch did it to ensure their rule and supremacy in the country at that time," Inge said.

The divide et impera (divide and rule) tactic worked.

Over the centuries, people of Chinese descent became more and more separate from the locals. They were seen as "the other" that lived among them yet not with them. Misunderstandings and prejudices also grew rampantly, perpetuated by discriminating treatment of the colonial government.

The Chinese still had to pay the highest taxes of all, under the supervision of Chinese captains and their assistants. Recognized for their penchant for making money, the VOC also assigned influential Chinese to manage some ports and markets to increase the colonial government's income.

The way the locals saw it, the Chinese collaborated with the Dutch to oppress them. Hatred grew, Inge explained.

So deep was the hatred that, even after the Dutch had left and the Japanese had come to rule the archipelago in 1942, many Chinese houses were looted and Chinese attacked, because they were seen as Dutch collaborators, Inge's book explains.

Erasing the stigma

The original copy of Inge's dissertation is now being displayed at Museum Pustaka Peranakan Tionghoa (Chinese-Indonesian Literature Museum) in South Tangerang.

The museum also displays more than 40,000 photos, books and documents that showcase Chinese-Indonesians' support in fighting for independence and their other significant achievements.

"Chinese-Indonesians, such as [badminton players] Susi Susanti, Rudi Hartono and Liem Swie King, have many achievements that make us proud," Azmi Abubakar, founder and manager of the museum, said. "But even that has not erased the negative stereotypes attached to them."

According to Azmi, Chinese-Indonesian associations were among the first to help after the tsunami in Aceh.

"But their good deeds were soon forgotten, and the stigma remained as if they had never done anything at all," Azmi said.

"Thanks to (Inge's) research, we now understand that the hatred and discrimination against Chinese-Indonesians didn't just happen. It was not only caused by the New Order regime but was the result of a very long (stereotyping) process that had lasted for centuries."

Inge hopes that her book will help bring awareness.

"I translated my dissertation into Indonesian, so that Indonesians can read and understand its contents. I want the readers to realize the stereotyping process and its impacts," said the grandmother of five.

"Indonesia belongs to us all."