Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsBattling stunting in East Nusa Tenggara: Healthcare and knowledge access

In the second part of our story about childhood stunting in East Nusa Tenggara, we look at how infrastructure and training are critical to reducing the prevalence of stunting.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

This is the second article of a two-part story. Read part one here.

The prevalence of childhood stunting in East Nusa Tenggara (NTT) has been ascribed to low public awareness, especially among caregivers and health workers. But the shortage in local food supplies, lack of sanitation and insufficient healthcare are also contributing factors.

A public health emergency, stunting underlines the reality that our health is not entirely in our own hands and is influenced by societal, environmental and cultural factors. More crucially, the success (or failure) of the authorities in providing sufficient public health care for all citizens is an indispensable contributor to maintaining health.

The puskesmas (community health center) is a cornerstone of the national health system, but according to a Databoks article on the Health Ministry’s 2015 Puskemas Basic Data report, a single puskesmas was serving the health needs of 26,000 people that year. This indicates the disproportionate number of registered health facilities that serve the naitonal population.

Difficult access

Albertus Hadat, a 69-year-old grandfather, recalls the long journey it once took to get a check-up at a public healthcare facility. Decades ago, traveling from his house in Liang Ndara village to the nearest puskesmas in Labuan Bajo took an entire day, although it is less than 28 kilometers from the village to the capital of West Manggarai regency, NTT.

"If we left early in the morning, we would arrive at Puskesmas Labuan Bajo in the evening. The road was bumpy and muddy, not to mention it could be a bit too dark, as we needed to cut through some forests to finally arrive at Labuan Bajo," Albertus told The Jakarta Post in May.

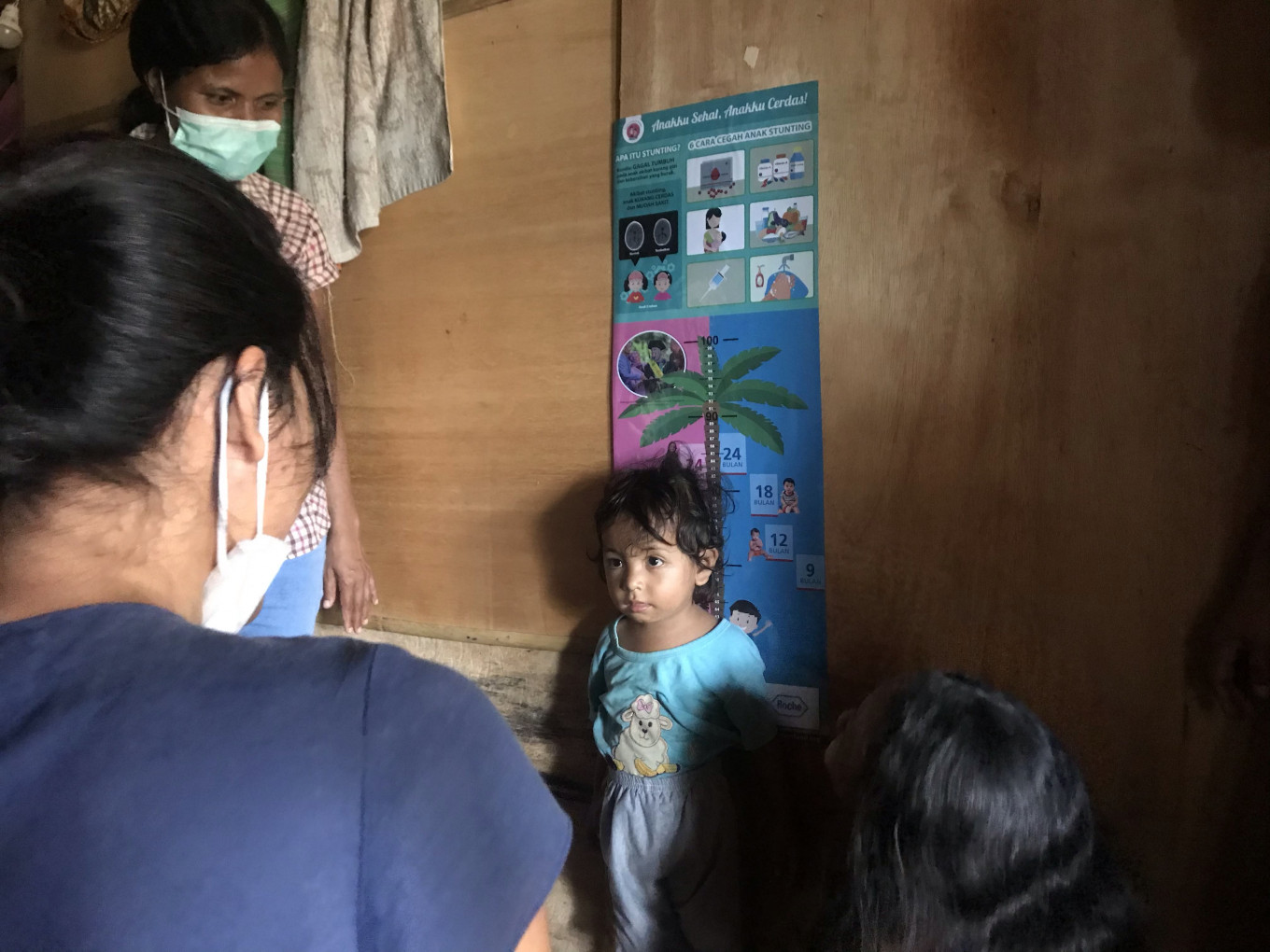

Direct education: Members of the 1000 Days Fund visit a family in Surunumgbeng village, 89 kilometers from West Manggarai regency's capital of Labuan Bajo. The NGO's stunting prevention program includes door-to-door awareness campaigns. (JP/Vania Evan)But things are looking up, as a puskemas pembantu (auxiliary health center) now stands just 500 meters from Albertus' house. While the availability of local healthcare facilities is no longer an issue for the residents of West Manggarai, their reluctance to make the trip still is.

A visit over two days in Liang Ndara as well as the villages of Tondong Belang and Lengkong Cepang on Flores Island, respectively situated around 45 minutes and 2.5 hours by car from Labuan Bajo, found that the road that connected them passed over very rocky terrain.

Irma, a 27-year-old mother of one who lives in Munting village near Lengkong Cepang. told the Post that most people still traveled on foot. The only available road to the local puskesmas passed through the hills, she explained, so this only weakened peoples’ drive and sense of urgency in visiting the puskesmas whenever they had a health issue.

As midwife Yosephina Kurnia told the Post, "Some [people] prefer home births because of the distance from their house to healthcare facilities. This could be dangerous for [both] the baby and the mother. Plus, they wouldn't get the postnatal care and education that they need. This could also lead to a higher risk of stunting."

Direct outreach

While healthcare facilities were growing in number and access was improving, the gap in local knowledge still needs to be filled in. This is where the 1000 Days Fund comes in, a Jakarta-based NGO pushing toward achieving zero childhood stunting in Indonesia by 2030.

Health workers Yosefina Berti and Emiliana Manul at Puskesmas Lengkong Cepang told the Post that they did not have proper onboarding training.

"If you are a mother in a village in eastern Indonesia, odds are you are taking your child to a posyandu (integrated health post) operated by kader [volunteer health workers] who have never had any training, which is something that keeps [my] team and me up at night. This is unacceptable, and we are doing everything to change that," stressed Zack Petersen, lead strategist at 1000 Days Fund.

Community effort: Health workers install a Smart Chart for measuring children's physical growth at a resident's home in West Manggarai regency, East Nusa Tenggara. (JP/Vania Evan)Equipping frontline health workers with the proper training goes a long way, as they hold one-on-one consultations with mothers in their own homes, a two-way conversation that helps build trust.

The NGO also makes and distributes “Smart Charts” in easy-to-understand language that is tailored for health workers, mothers and families. It is designed to be hung on walls as a daily reminder to measure a child’s height and assess their nutritional needs. According to its website, the NGO has distributed 43,000 Smart Charts across 28 islands to date.

However, delivering factual, science-based information to people with different education levels remains a challenge. Senior program manager Sisi Arawinda of 1000 Days Fund says that the main obstacle is simplifying the information for easy comprehension.

"It is very natural for people to forget the information they have heard just once, so we need to keep repeating the same information until it sticks in their mind," she said.

The organization does this alongside regular monitoring, as it believes that frequent small campaigns will have more far-reaching, long-term impacts than major one-off campaigns. Despite the challenges, 1000 Days Fund finds fulfillment in the measurable results of their work.

"My reward comes from every 'Ah, I see!' that I have received over time. Knowing that you can give people information that they haven't been aware of before, it is worth more than money," Petersen said.

In the same vein, finance and project officer Velo Theresia said what was most rewarding was when mothers and health workers engaged in the conversation by asking questions, showing that they were paying attention.

Continuous training: Members of the 1000 Days Fund run a training program on childhood stunting for 'kader' (volunteer health workers) in West Manggarai, East Nusa Tenggara. (JP/Vania Evan)Still, aiming for Indonesia to be totally free from stunting seems an ambitious goal. According to Petersen, however, the aim is not to eliminate stunting, as other factors can sometimes stand in the way.

"Here's my finish line: Ninety percent of all pregnant women in Indonesia is examined six times during their pregnancy, and 90 percent of all kids below five years old are measured," he said.

As the saying goes, “What gets measured gets managed.”

According to the World Bank, stunting prevalence contributes losses amounting to 2-3 percent of Indonesia’s GDP, but for families, preventing stunting is more than just statistics.

"My granddaughter Septi is not only the hope of our family, but also the hope of our neighbors, the hope of [our] kampung, the hope of [the island] and ultimately, the hope of Indonesia," said Albertus.