Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsTo veil or not to veil, Islamic women face tough choices

When Wina decided to shed her jilbab, the headscarf symbolizing, for most people, a woman’s commitment to Islam, her husband commented, “It’s up to you, but it’s degrading

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

W

hen Wina decided to shed her jilbab, the headscarf symbolizing, for most people, a woman’s commitment to Islam, her husband commented, “It’s up to you, but it’s degrading.”

She said some of her colleagues at work started gossiping and were cynical toward her following her decision to remove the scarf after three years wearing it.

Wina, a thirty something Jakarta resident, had been one of the subjects in the book “Psychology of Fashion”: Fenomena Perempuan Melepas Jilbab (Psychology of Fashion: The Phenomenon of Women Removing Their Jilbab), launched Tuesday in Jakarta.

The author, Juneman, a psychologist from the University of Persada Indonesia, interviewed three other women who also decided to shed their headscarves.

The choice was often met with shock and criticism — some soft and others openly harsh — from their friends and family.

Intan, a citizen from West Java, said she had a long argument with her mother after deciding to take off her veil and said her mother accused her of being “wishy-washy”.

In the book, Intan recalled her mother’s words: “See? I told you so. You didn’t have to [wear a jilbab] now you’re embarrassed, right?”

The book revealed that social institutions and peer groups often play a large part in influencing a woman’s decision to wear the Islamic head-scarf. And they are quick to react to women’s decision to remove it regardless of the fact that such a decision is a private one.

“I often get comments on my Facebook page, saying that I would look prettier in a jilbab ,” said Tia — not her real name — who attended the book launch.

The woman in her thirties said that despite similar nudges from friends and colleagues, she would still put off donning a scarf.

Four of the women in the book said they were encouraged to wear the head scarf by institutions such as religious organizations and schools, and by male figures.

Intan in particular recalled her public junior high school teacher teaching students that women who refused to wear the jilbab were bound to hell.

The women interviewed in the book shared their various reasons behind their decision to remove their jilbabs. Tari from West Java was disillusioned by the election process for the head of the women’s division of her campus’ religious group. She said rumor was rife that candidates had to wear the very conservative hijab, which covers more than just the head and shoulders.

“This is not right. How come a woman’s worth is judged by the size of her jilbab,” she said.

Lanni from East Java said that one of her reasons was having her heart broken by the man who encouraged her to wear a jilbab. While for Intan, studying Hindu and Buddhist philosophy during college had been one of the antecedents.

Juneman said the reason to shed the jilbab fell into two categories: the feeling that one is not “enlightened” or pious enough to wear one, or, on the contrary, feeling that they are already enlightened thus felt that the attire was unnecessary.

Three of the women said they felt more comfortable after taking off their jilbabs, and two said they may return to wearing the headscarf again in the future.

All of the four women had finished undergraduate degrees and were living in major cities when Juneman conducted the book’s research in 2007. When he first announced he needed subjects for the research over the Internet, more than 10 women expressed their interest over the one month waiting period.

“The nature of this research [qualitative], is not a representative one,” Juneman said.

Siti Musdah Mulia of the Conference For Religion and Peace said that it was only after the 1980s

that jilbabs became a major phenomenon in Indonesia, and the movement had grown more significantly in public schools rather than religious ones.

“For pesantren [Islamic boarding school] students, the headscarf was just considered as part of the uniform, there were no talks of hell for those not wearing jilbabs there,”

she said.

Siti added that there were other changing habits regarding how people viewed religion. For example, in the past there were no unwritten rules that lectures should pause during the call to prayer.

She illustrated less rigid methods of wearing jilbab that she encountered during her student days at a university in Cairo.

“Some female students only put on their scarves in class,” Siti said.

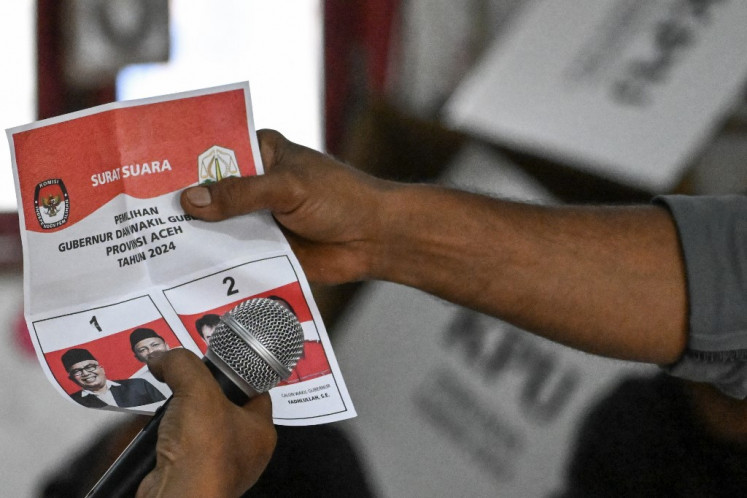

Some regions, which won autonomy since the fall of Soeharto’s centralist government, have imposed Islamic dress codes on women.

In some regions, such as several parts of Aceh, failure to adhere to these codes can lead to punishment under sharia law.