Pancasila a ‘religious laicity’ for the world ?

A seminar recently organized by the French Embassy and the Leimena Institute brought together Muslim scholars from various institutions around the ambassadors of France, Germany and the European Union

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

A

seminar recently organized by the French Embassy and the Leimena Institute brought together Muslim scholars from various institutions around the ambassadors of France, Germany and the European Union.

Entitled “Pancasila and the European models: Toward mutual inspirations,” this event highlighted ways to overcome harsh opposition between secularism and Islamic governance which often ends in deadlock.

As an illustration Pancasila could be a source of universal inspiration and that it is possible to draw a fruitful parallel between the religious ideology of the Indonesian state and French laicity.

The first argument that comes to mind when thinking about the potential universality of Pancasila is the fact that it is the product of multiple influences including foreign ones.

Unlike most Muslim-majority countries that had to choose urgently, and sometimes painfully at the time of their independence, between a secularized regime and the adoption of Islam as the state religion, Indonesia is one of the rare cases in which in-depth political debates were held on the relation between religion and the state.

If one wants to have an idea of the diversity of references mobilized in the collective debate and deliberation which led to the adoption of Pancasila, one needs only to read the famous speech of Sukarno later called “the Birth of Pancasila”.

Indonesia’s founding father proposed to adopt five principles of Pancasila with reference to Negarakertagama. He acknowledged the influence of Sun Yat Sen, the founder of the Republic of China, quoted Ernest Renan, the French historian of national identity, and also Mahatma Gandhi.

He was also influenced by modernist Islamic thinkers, whom he had discovered during his stay in Surabaya with Tjokroaminoto, the leader of the Sarekat Islam.

The extremely clever combination of Javanese, Muslim, Western and oriental influences ofPancasila can also be read in the manner in which the first principle was enunciated, especially its first principle.

To use Sanskrit (maha esa) to express a strong tribute to the Islamic belief in God is the symbol of Indonesian ingenuity that acknowledges a diversity of influences, refuses to occult any part of Indonesian history, and which aims to formulate a common basis for all spiritualities.

Why use the term “laicity” to refer to the Indonesian approach to the place of religion within the state? The first reason is semantic: it allows us to avoid using the term secularism, which, especially in Indonesia, would risk distorting the debate due to its semantic proximity to the terms “secularize” and “secularization.”

The second reason is related to the universality: If the term “laïcité” is a French linguistic invention, the founding fathers of laicity in France have never conceived of it as a “French exception”.

The third reason is that the comparison between these different approaches to the place accorded to religion within the state, invites us to distinguish between what is essential and must remain intangible and what is more cultural and may be subject to debate.

As for the intangible, the aspiration in both countries is identical: the state should allow its citizens, regardless of their religion, to cohabit harmoniously. Beyond these general principles, to understand the peculiar complexion of laicity in France and in Indonesia, we have to keep in mind their very different historical contexts.

Laicity was established in France to keep Catholic Church at bay, because of its role in an unjust authoritarian regime (the monarchy).

In Indonesia things were very different, since the values of freedom, equality and fraternity claimed by the motto of the French Republic were supported by the whole nationalist movement and in particular by the Muslim organizations which were an essential pillar of the mobilization against colonization.

Islam, the majority religion, was therefore not associated with an earlier authoritarian regime. Consequently there was an early widespread consensus that the state should be religious and discussions focused on the form this recognition should take; laicity in Indonesia rested on a close collaboration with Islam but without exclusive recognition.

Laicity has a different history in our two countries but with the same purpose and it is based on comparable principles. But neither are fixed models and to compare them help us to understand the evolutions they have undergone but also the factors which can threaten the social harmony that they intend to promote.

Such a comparison can above all shed light on the debates, often very heated in our two countries, surrounding the role of religion within the state. These debates are not only legitimate but they are also desirable since the consensus about these essential values of living together must be constantly renewed.

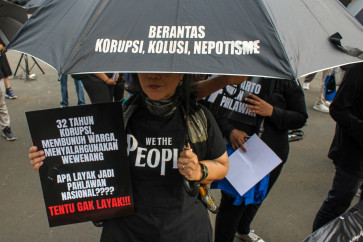

The French philosopher Paul Ricoeur defined laicity as a “space of reasonable disagreement,” framed and guided by reason. Debates about the place of religion must therefore be based upon knowledge, intelligence and respect. These debates cannot be reduced to empty slogans, insults, street demonstrations and political manipulations.

Three institutions therefore have a special responsibility in this respect: Religious and social organizations in order to represent diverse sensibilities; universities to provide knowledge and reason necessary for these debates, and finally the state to guarantee the freedom of expression and the rights of minorities and to prevent violence, intimidation and instrumentalization.

____________________________

The writer is a senior researcher at the French National Center for Scientific Research (CNRS) and member of the European research project CRISEA.