Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search results‘Had I known, I would have not gone this far’: Farmer fights politically wired mining firm

In 2017, he was accused of displaying a banner with a hammer and sickle logo on it during a rally in opposition to gold mining. The court later found him guilty and sentenced him to four months in jail.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

H

eri Budiawan had just returned to Sumberagung village in Banyuwangi, East Java around August 2010 after working in Saudi Arabia for 10 years, and he found that his hometown had changed much because of gold mining in the nearby Tumpang Pitu mountain range.

Before 2014, mining company PT Indo Multi Niaga had carried out exploration to find gold there. Everything changed around 2014 when the company struck gold and began the pre-construction phase for the gold mines. The permit also changed hands from Indo Multi to PT Bumi Suksesindo (BSI).

BSI, a subsidiary of PT Merdeka Copper Gold, took over mining operations in 2012. It has been running the mining operation ever since.

During the pre-construction phase in 2014, Heri, also known as Budi Pego, said residents spotted major changes to their environment’s landscape. He accused BSI of, among other things, flattening the mountain, clearing the forest and blocking the river that was the primary water source for the residents.

“That was the beginning of our protest to the mining company, as well as my fight for my hometown’s environment,” Budi told The Jakarta Post in a recent interview.

Read also: Activists call for postponement of environmentalist Budi Pego's imprisonment

BSI spokesperson Teuku Mufizar Mahmud dismissed such claims, saying the company had been working with the local administration to repair and construct roads leading to the mining complex. He added that the company had also implemented high water treatment standards to prevent the disruption of the local water supply.

“We have also done forest and land rehabilitation, both permanent and temporary, in areas we cleared previously to increase land productivity and prevent landslides,” Mufizar told the Post.

Before protesting the gold mining operation, Budi said he did not have much knowledge about the environment as he had not completed formal education in senior high school.

“I just don’t want people to get caught in an accident by using the roads that have been damaged by the company’s heavy machinery and trucks,” he said. Budi added that he later obtained knowledge about the environmental damage from a village head and fellow activists after getting involved in protests.

He said he was unintentionally seen as a leader of a protest movement by fellow residents because he headed several religious activities in the village. Budi said he was a member of Nahdlatul Ulama, Indonesia's largest Muslim organization, because he attended a madrasah tsanawiyah (Islamic junior high school).

Budi, who worked as a dragon fruit farmer after returning from Saudi Arabia, said the mining operation had also affected agricultural productivity in the area. After the gold mine began operation, he claimed there was a significant drop in the fruit yield during harvest.

This prompted him to get involved more in protests against the company, which ranged from demonstrations by residents and to a roadblock against BSI vehicles.

The fight, however, did not always end on good terms for Budi and fellow residents, as they were often slapped with criminal charges for their protests. In November 2015, eight residents were named suspects for allegedly damaging the company’s property. Four of them were found innocent, while the others are still appealing the case at the Supreme Court.

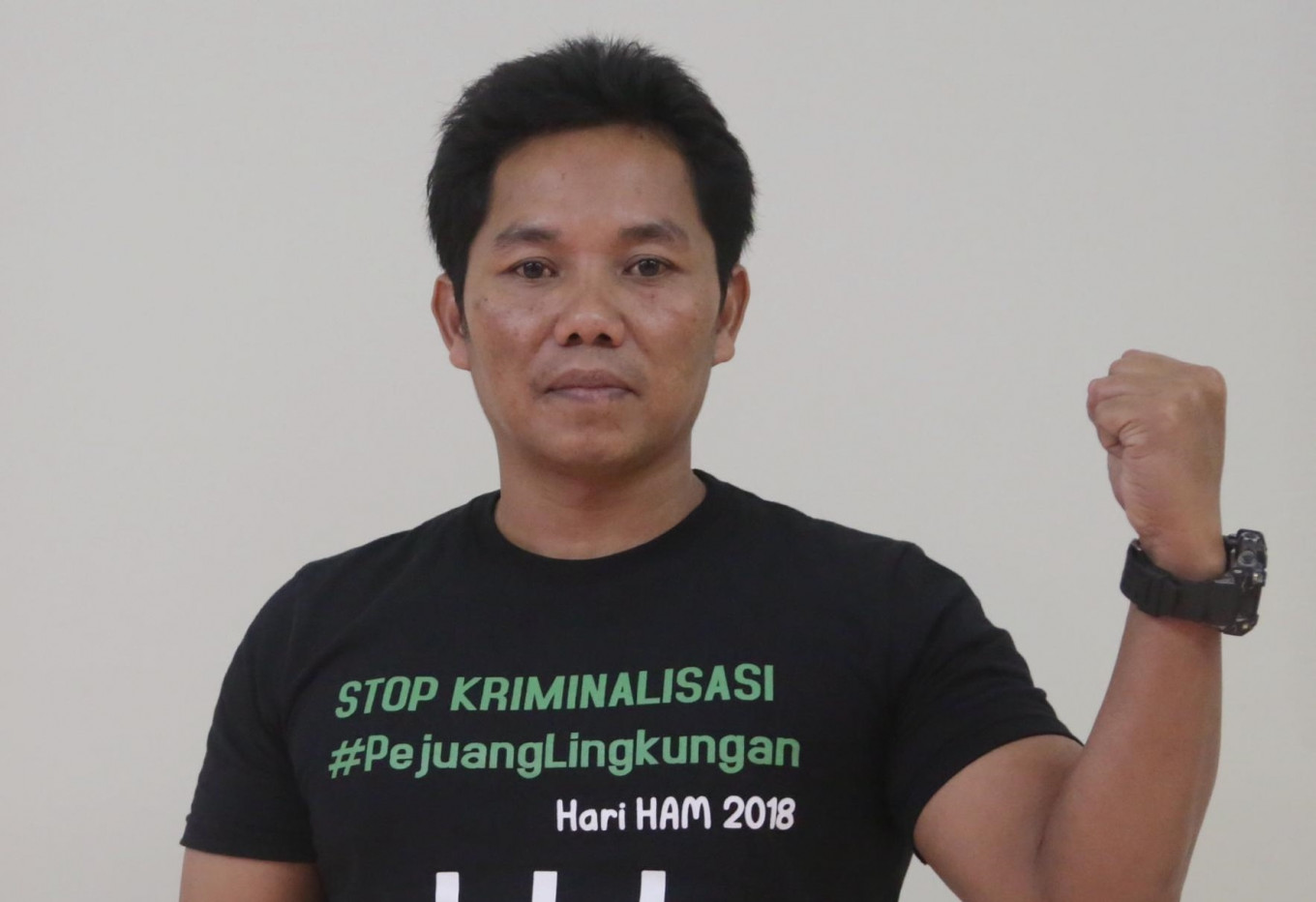

Budi was the latest to join the line. In 2017, he was accused of displaying a banner with a hammer and sickle logo on it during a rally in opposition to gold mining. The court later found him guilty and sentenced him to four months in prison.

It was the first time that Budi learned that BSI was a subsidiary of PT Merdeka Copper Gold, a publicly listed mining unit of investment firm PT Saratoga Investama Sedaya and PT Provident Capital Indonesia.

According to Merdeka Copper Gold's and Saratoga Investama Sedaya's websites, several people sitting on their boards of commissioners are connected to the country's top politicians.

Budi said he had no idea how politically wired the company was.

“I thought this was only a small mining company. I really didn’t know there were powerful people behind the company,” Budi said, laughing. “Had I known it from the first time I launched the protests, I would have not gone this far.”

Budi admitted his protest had affected his personal life, as well as his wife and two daughters. “Because of the protests, I couldn’t focus on tending to my dragon fruit farm. We only earn a small amount of money now.”

Upon being released from prison in July 2018, he said his family had suggested he cut his protest activity because of the effects inflicted on the family.

“However, I refuse to back down, because who else is going to fight for the environment?”

After being sentenced to the additional four years in prison by the Supreme Court in November 2018, Budi and other activists have been fighting to prove the former’s innocence in the case.

Budi was seen by many as an environmental defender thanks to his fight for “the human right to a healthy environment”, said Rere Christanto, the Indonesian Forum for the Environment director in East Java.

“This string of legal cases is not only a blow for Budi and his family and environmentalism that fights for the rights to a healthy environment, but also for the Indonesian civil movement in general. Unfortunately, this is not the only case in the country,” Rere said.

According to Protection International Indonesia, there were at least 104 cases of rights violations involving environmentalists and people defending their land from 2014 to 2018. Many of them have been sent to jail on what activists believe are dubious or legally flawed charges.