Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsHeat may curb COVID-19 spread in Indonesia. But don’t count on it, scientists say

A study points out several attributes and patterns of COVID-19 that are similar to other coronaviruses, such as SARS and MERS, which have proven to be sensitive to higher temperature, to back up its argument that the virus may be at its most active and potent in lower temperatures, particularly during the winter.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

An Indonesian health official checks body temperature of a foreign tourist arriving from Bali island heading to tourist area Gili Trawangan at the Bangsal port in Pemenang Lombok island on February 12, 2020. - The COVID-19 coronavirus that emerged in central China at the end of last year has now killed more than 1,100 people and spread around the world. (AFP/Moh El Sasaky )

An Indonesian health official checks body temperature of a foreign tourist arriving from Bali island heading to tourist area Gili Trawangan at the Bangsal port in Pemenang Lombok island on February 12, 2020. - The COVID-19 coronavirus that emerged in central China at the end of last year has now killed more than 1,100 people and spread around the world. (AFP/Moh El Sasaky )

Could its tropical climate prevent Indonesia from descending into a major COVID-19 outbreak as seen in South Korea, Iran and Italy?

It’s possible, scientists say, but cautioned that governments should not rely on weather to fight the virus.

At least two newly published studies have suggested that the viral transmission rate of the 2019 novel coronavirus, which causes COVID-19, may be linked to temperature and seasonal fluctuations across different regions.

Like SARS and MERS?

One such study — which has not been peer-reviewed yet — finds that higher temperatures may render the virus less potent and ultimately inactive, which may explain why countries with consistently warmer climates, such as Indonesia, have reported fewer COVID-19 cases than temperate regions where temperatures vary between 5 to 11 degrees Celsius and 47 to 79 percent humidity.

Indonesia has reported 34 confirmed cases of COVID-19 as of Thursday, far below the numbers reported by neighboring Malaysia (149) and Singapore (178). While the official figure given by Indonesia seems implausible, the numbers reported by Malaysia and Singapore are also far below those of South Korea (7,869), Iran (9,000) and Italy (12,462).

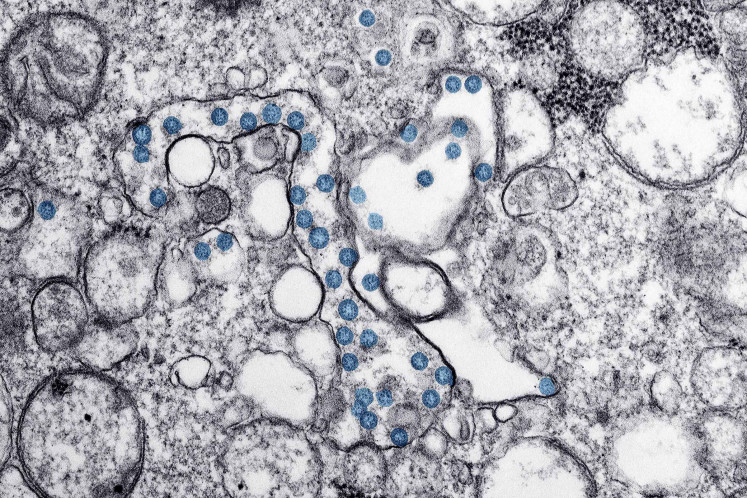

An isolate from the first U.S. case of COVID-19, formerly known as 2019-nCoV or novel coronavirus, is seen in a transmission electron microscopic image obtained from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) in Atlanta, Georgia, U.S. March 10, 2020. (Reuters/CDC/Hannah A Bullock and Azaibi Tamin)

Conducted by a team of scientists from the Institute of Human Virology at the University of Maryland in the United States in conjunction with the Global Virus Network, the study suggests that, based on the number of reported cases across the globe, COVID-19 may become less potent and, therefore, result in fewer casualties in the tropics.

The study points out several attributes and patterns of COVID-19 that are similar to other coronaviruses, such as Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS), which have proven to be sensitive to higher temperatures, to back up its argument that the virus may be at its most active and potent in lower temperatures, particularly during the winter.

Furthermore, the study predicts that hardest-hit countries situated within the more temperate corridor of the planet’s climate – which, at the time of writing, includes outbreak epicenter China, Iran and Italy – are likely to report fewer COVID-19 cases in the months leading up to summer.

“Although it would be even more difficult to make a long-term prediction at this stage, it is tempting to expect COVID-19 to diminish considerably in affected areas [within the temperate regions] in the coming months,” the report said.

Iranian firefighters disinfect streets in southern Tehran to halt the wild spread of coronavirus on March 11, 2020. - The novel coronavirus outbreak in Iran is one of the deadliest outside of China and has so far killed 291 people and infected more than 8,000. (AFP/Atta Kenare)

Another study, conducted by a team from Sun Yat-sen University in Guangzhou, China, finds that COVID-19 may be at its most active at a particular temperature.

The analysis, which is based on the team’s study on every novel coronavirus cases confirmed around the world between Jan. 20 and Feb. 4, including in over 400 Chinese cities and regions, indicates that the number of reported cases have been congruent with average temperatures up until they peaked at 8.72 degrees.

The number of reported cases subsequently declined at the same time temperatures continued to rise, the study claimed.

Bayu Krisnamurti, former head of the now-defunct national committee for avian flu in Indonesia, shared the optimistic outlook on the correlation between the transmission rate of the novel coronavirus and temperature fluctuations.

The viruses that cause influenza are known to be sensitive to temperatures, he said.

“It is customary for people in countries with four seasons to take flu shots in the fall,” Bayu said, explaining that past flu pandemics have shown a pattern of peaking before stagnating and finally slowing down.

Bayu said he did not know whether the novel coronavirus, which caused an influenza-like illness, would behave the same way as the flu, but added that “we could assume it would have the same behavior”.

People stand in a long queue to buy face masks at a post office, after a shortage of masks amid the rise in confirmed cases of the novel coronavirus disease COVID-19, in Daegu, South Korea, March 4, 2020. (REUTERS/REUTERS/Kim Kyung-Hoon)

Despite the optimistic findings, however, the study still calls for immediate adoption of “the strictest control measures” to prevent future outbreaks in countries and regions with lower temperatures.

Contradicting results

The caution is not unwarranted.

A separate study conducted by a group of researchers, including epidemiologist Marc Lipsitch from Harvard’s T.H. Chan School of Public Health, yielded contradicting results, claiming that “sustained transmission and rapid growth of cases are possible over a range of humidity conditions ranging from cold and dry provinces in China”.

It went on to note that changes in weather alone would not necessarily lead to immediate declines in the number of confirmed cases without “the implementation of extensive public health interventions”.

Panji Hadisoemarto, an infectious disease control expert from Padjajaran University, also conveyed his skepticism regarding studies that claimed the novel coronavirus’ transmission might be linked to temperature fluctuations, arguing that heat might only “slow down transmission, but very likely not enough to stop it”.

Pigeons gather on Piazza del Duomo by Milan's cathedral on March 10, 2020 in Milan. - Italy imposed unprecedented national restrictions on its 60 million people on March 10, 2020 to control the deadly coronavirus, as China signalled major progress in its own battle against the global epidemic. (AFP/Miguel MEDINA)

“There has yet to be any proof that [the virus] could be transmitted through the air. It can be transmitted directly through close physical contact, via droplets, such as when an infected individual coughs in front of an otherwise healthy person,” he said.

That said, he explained that indirect transmission — when an individual contracts the virus after coming into contact with an object that contains traces of infectious droplets — could be affected by shifts in temperature, as this type of transmission relied on the virus’ survival outside of its host.

“Therefore, the impact of temperature depends on the contribution of indirect transmission to the spread of the virus. Unfortunately, we have yet to know for sure, but I’m confident that direct transmission plays a bigger role in the outbreak, especially in densely populated areas,” Panji said.

Tourists sit at a table at a largely empty Chinatown district as tourism takes a decline due to the coronavirus outbreak in Singapore February 21, 2020. Picture taken February 21, 2020. (REUTERS/Edgar Su)

Mohammad Sajadi, the lead author of the University of Maryland’s paper, defended his research, saying that while he did not know the situation in Indonesia or whether its government was hiding its statistics, the country might yet see a massive outbreak.

“Based on my personal knowledge of COVID-19 in other countries with known high case numbers, when there is significant community spread, it is not subtle, and the hospitals get overrun, and it’s near-impossible to hide,” he said in an email.