Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsRethinking the role of technology in elections

Sirekap is merely a system to assist with the counting process and publicize the results, not a system to establish the official outcome.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

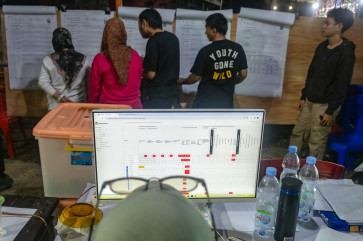

to Anyone

District Polling Committee (PPK) officials input vote counting data into the Tabulation Information System (Sirekap) in Palu, Central Sulawesi on Feb. 21, 2024. The vote-counting at the district level in Palu uses Sirekap application despite an instruction from the General Elections Commission (KPU) to suspend the tabulation using the app as the commission synchronize data in the platform with the one from the manual C1 vote tabulation form. (Antara/Basri Marzuki)

District Polling Committee (PPK) officials input vote counting data into the Tabulation Information System (Sirekap) in Palu, Central Sulawesi on Feb. 21, 2024. The vote-counting at the district level in Palu uses Sirekap application despite an instruction from the General Elections Commission (KPU) to suspend the tabulation using the app as the commission synchronize data in the platform with the one from the manual C1 vote tabulation form. (Antara/Basri Marzuki)

This year's election was probably the most technologically advanced one the country has ever held. Technology influenced the landscape and dynamics of the election, with some finding it beneficial and others not so much.

On the campaign trail, for instance, technology assisted the reinvention of Prabowo Subianto, the presumptive winner of the presidential race based on quick count results. Using generative artificial intelligence, his image was transformed from the controversial 72-year-old ex-Army general into a gemoy (adorable) grandpa. This indicator demonstrates the power of technology in altering the substance of the message, something so successful that it was unthinkable during the previous presidential election five years ago.

The technology-use case further showed its usefulness in significantly increasing the campaign's coverage. On TikTok, one of Indonesia's fastest-growing social media platforms, posts labeled with the #Prabowo hashtag received up to 19 billion views, demonstrating how short-form mobile videos with catchy music could be the future of political campaigns in Indonesia.

As in the election process itself, the General Elections Commission (KPU) initiated the use of technological innovations in the form of optical mark recognition (OMR) and optical character recognition (OCR) within its input process in Sirekap, though the efficiency has yet to be proven due to current controversies arising from the incorrect conversion of the numbers.

Even in that regard, technology shows its might. Some recurrent initiatives, such as KawalPemilu.org, act as crowdsourcing platforms for netizens to independently tabulate votes using real-count technology, basically matching the data to that provided by the KPU. What is different about this year's election is that netizens live-streamed the vote-counting process at their polling stations using TikTok, revealing the process' transparency in real-time.

Aside from those encouraging advances, it is apparent that Indonesia still has a long way to go in terms of effectively utilizing technology in its democratic process. Most people look an example to Estonia in this regard, where more than half of the ballots in the 2023 parliamentary (Riigikogu) election were cast electronically (e-voting), 19 years after the system was adopted in the country.

As Indonesia has had a bit of a taste of technology in the 2024 election, some people have already found it to be rather problematic. Social media is believed to have raised the gimmickry campaigns in the 2024 elections, and the technology employed by KPU in the vote-counting process, which has been made public, is possibly misleading because the public discovered several mistakes in the input.