Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsThe painter behind 'pecel lele' banners

The ubiquitous paintings found in street food stalls did not arrive from nowhere; it came from one painter in East Java with big dreams

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

A

middle-aged man, with a flat cap on his head and a collared shirt, sat quietly as his eyes stared down the 12-square-meter banner in front of him. The flashy neon green fabric was still plain. There were only thin sketches of chickens, gourami fish and other drawings of animals recognizable on the banners of a pecel lele warung (deep-fried catfish food stall). Pecel lele is of course the popular Indonesian dish that originated in Lamongan, East Java, but now can be had anywhere across the country.

Many times he tried to land his brush to embolden the sketch lines, yet over and over again he refrained from doing so - inspiration was not with him today. His name is Teguh Wahono, the unsung maestro who created the iconic pecel lele banner, whose style is so ubiquitous that it is difficult to think of any other drawing style warung banners would employ.

“Hot days like this, all the ideas in my head evaporate. My head feels like it’s boiling. I'll just continue this in the afternoon. For now, let's have a cup of coffee," he said with a laugh.

Inside his studio, built in a large cement-walled room located in Bulutengger village, Lamongan, Teguh Wahono has created thousands of pecel lele banners. Warung, which are spread across Indonesia, are like open galleries that never fail to showcase Teguh's creations.

The pandemic has not helped business. Previously averaging 10-15 banners monthly, Teguh’s income has dwindled to half of what it used to be. The warung, his regular clients, are closing down. The banners cost an average of Rp 250,000 (US$17.74) per meter, with each warung averaging 3-4m, and the banners lasting for about six months before the weather and rain forces the warung to get a new one. But the pandemic has meant far fewer orders.

“Things are up and down [for the warung business]," Teguh says, “They’re lucky if they haven’t gone bankrupt," he continued.

Journey and dreams

Painting pecel lele banners is Teguh's only source of income. It has been his profession since the early-1980s when he was still in high school. His dreams of becoming an artist made him view formal education as nothing but a boring routine. Teguh made the decision to drop out during his final year of high school and move to Jakarta in 1983. After months, with little more than a brush and paint - and no art career on the horizon - Teguh offered his services to every warung he ran into, for whatever they were willing to pay him. He lived with various warung owners who were kind enough to let him sleep in their homes, making extra money selling soto Lamongan (a broth-based dish). But eventually it worked, and his style became the go-to illustration for the food stalls since then.

Teguh Wahono rests down in his studio, where students learn about drawing pecel lele banners before producing their own (Courtesy of Yongki Satria/Yongki Satria)After more than three years, Teguh, then 22-years old, was making a steady enough income to support himself and save money. He decided to return to his village to realize his dream of building a studio for village children who, like him, aspired to become artists.

“One of the things that bothered me the most when I wanted to be an artist was the location of [Bulutengger village] which is far from any art gallery. Our parents did not give us permission to become artists because they didn't understand what it was,” Teguh recalled. His own parents were not initially supportive but came around, with his father naming his studio.

"The name was ‘Caesar’. It stands for calon enak sampai akhirat [to live comfortably for eternity],” Teguh explained with a hearty laugh.

Before the days of lele, Teguh aspired to be an abstract painter. He idolized the legendary Indonesian painter Affandi, however he has now accepted his destiny.

"I had to put my ego aside first. I also wanted to exhibit in galleries. But if you think about it, we should just always be grateful for what we have," Teguh stated.

Teguh's dream to promote his village as the center of the pecel lele banner is slowly coming to fruition. It now has a number of students who have opened their respective banner studios.

The past year has been challenging.

"The coronavirus restrictions have caused people to turn to digitally printed banners. They’re cheaper and last longer. They don't really care that the picture doesn't look good, or how the printed banner material makes the warung look dark and shady. All they think about is that it's cheap,” Teguh said.

Moreover, raw materials such as paint and even the banner fabric, which are usually imported from abroad, have undergone drastic price increases. Smaller banner studios have gone bankrupt, forcing a change of career for the painters.

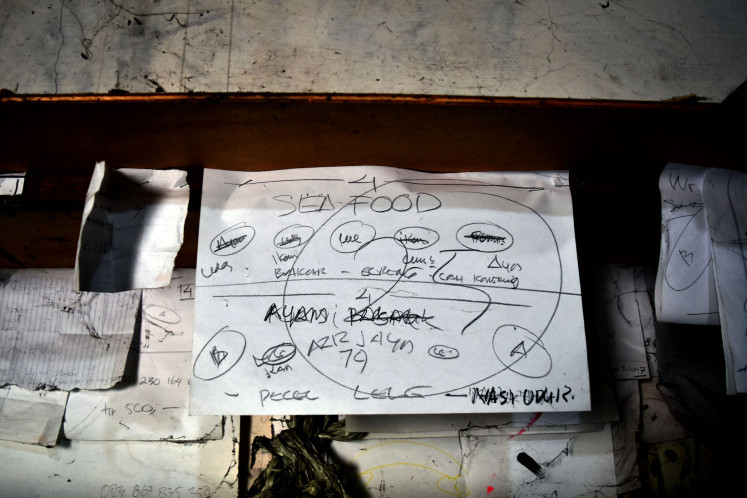

Teguh Wahono’s layout sketches (Courtesy of Yongki Satria/Yongki Satria)"I'm sometimes jealous,” he admits. “On television, Facebook, and many other platforms, there are many donation programs for musicians, the film industry, for professional painters, things like painting auctions. But for small artists like us - who cares about us? Nobody. Mostly because what we do is considered cheap art, right?" Teguh said.

Teguh jokingly said that even legendary artists would not necessarily be able to paint banners with such neat color gradations. "Even Pak Affandi or Basoeki Abdullah are not as good at painting ducks, chicken, or tempeh as I am," joked Teguh.

Making pecel lele the main dish

In Teguh's early days as an artist, most warung in Jakarta focused on soto Lamongan, with the pecel only acting as side dish. It was an aesthetic mindset that made it the center of Teguh’s posters and eventually, the main menu item in warung.

"The experiment was born out of my mischief. The Javanese would say that it's ngakal [experimenting with ideas]. What came into my mind was that the words 'pecel lele' only have four main letters, P, E, C and L. That made it easier for me to make a pattern. I also thought that the nine-letter composition looked good. It can be put right in the middle. It's easier to be painted. Now I have my works imitated by every other banner painter. Thank God, I’m a useful artist!” Teguh chuckled.

Experimentation —or what Teguh describes as an artist's mischief—has changed the street food trends over the ages. Pecel lele banners are spreading far and wide, and we can easily find them in every corner of all cities throughout Indonesia.

Said Teguh, “My goal is simple. I just hope that this pecel lele banner painting tradition will continue to exist even though printing is getting more sophisticated. So that if I were to pass away, I will have a memento - a legacy that will be carried on by every pecel lele banner painter in the future.”