The man who introduced Wonogiri chicken noodles to the rest of Indonesia

Vendors pushing wooden carts and selling Wonogiri chicken noodles have become a common sight in Indonesia. Their stories begin with one man.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

R

atiman first arrived in Jakarta in 1963. It was President Sukarno's final years in power, and slums and poverty quickly became a familiar scene for the then-22-year-old.

Still, the city promised a better future for Ratiman. He left behind his home, Tunggulrejo in Wonogiri, Central Java, the mountainous landscape of which caused endless droughts and resulted in a monoculture dominated by cassava. Working on cassava fields for the rest of his adult life was something Ratiman dreaded, and he saw Jakarta as a way out.

Once in the capital city, Ratiman spent almost a decade working any odd jobs he could find, before landing his first steady job, that of a noodle maker in a factory owned by a Chinese-Indonesian businessman. The factory was located on Jl. Belustru at Pasar Market in central Jakarta. The market was the country’s largest at the time.

With his newfound noodle-crafting skills, Ratiman began selling his own chicken noodles during his off hours. These noodles were made Wonogiri style, which is now arguably the most common type of “chicken noodle” in Indonesia. It uses plenty of white and fried onion and garlic, pieces of chicken and chicken skin, and seasoning made from elements of ginger, coriander and turmeric – among other ingredients.

Ratiman wandered around the market area and beyond, pushing his wheeled wooden cart, trudging through the muddy fields north of Glodok, West Jakarta. His boss didn’t mind, since Ratiman proved himself to be one of the strongest workers at the factory. He was working his way up.

The boss’ wife

When his boss passed away, Ratiman was kept on board by the boss’ wife and played an increasingly key role in the factory. As he became more involved in the business, he married his deceased boss's wife. This ostensibly made him the factory’s new head.

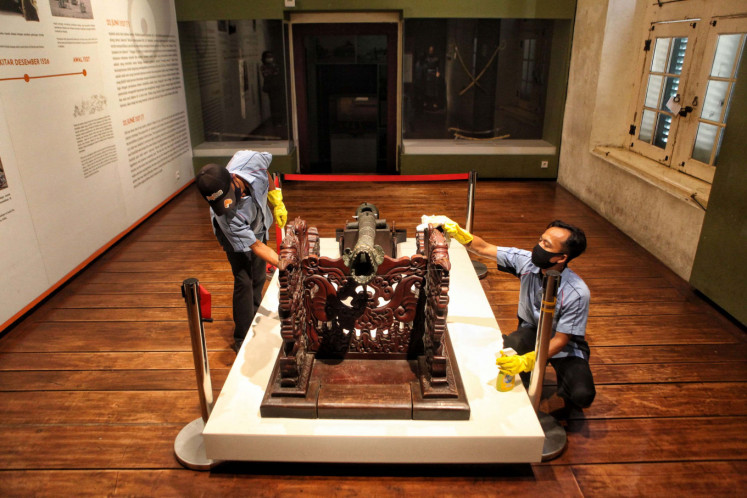

Ratiman came up with an idea to expand the noodle factory’s reach. He invited his family and relatives to Jakarta to support the business. Ratiman made most of them sell bowls of chicken noodle on carts – something that he himself was no longer doing, as his responsibility in the factory had increased.

This was the start of wooden-cart chicken noodle sellers, a tradition still seen today in the streets, in front of offices and schools, and in neighborhoods. Mie Ayam Wonogiri remains ubiquitous.

Ratiman died in 2003 at the age of 62. His daughter, Tri Murtini, 50, recalls how, as a child, she had seen her father’s business grow rapidly. Tri was one of three children Ratiman had with his second wife (Ratiman was a polygamist).

By the 1980s, Ratiman was managing around a thousand carts covering Jakarta and its neighboring cities like Bekasi, Bogor and Tangerang. Within a day, his factory would grind 150 sacks, each consisting of 23 kilograms of flour, to make the noodles.

Keep it in the family

His brothers also found success. They opened other factories in Manggarai and Sunter (both in Jakarta) and Cipadu in Tangerang, to help cover the ever-growing need for noodle supplies.

Ratiman moved his factory from Pasar Atom to Jembatan Tiga in Central Jakarta, right behind his house. Tri inherited the house and succeeded the factory.

Though the business had slowly shrunk as other noodle factories grew, Tri has kept her company running.

Just like her father, she continues to support people who want to start their own chicken noodle business.

"I make them the carts. All the cooking utensils, such as bowls, stove and crockery, are from me. It is not cheap. It costs Rp4 million for one cart," she said.

These days, the factory supplies noodles for 300-400 Mie Ayam carts around Tangerang, Bekasi and Jakarta. It grinds 800-900 kilograms of flour a day.

Tri remains proud of her father. She said that many a villager from Wonogiri who joined the business had become successful. Many have started their own Wonogiri noodle businesses in provinces like North Sumatera, Lampung and Riau Islands.

Even the government recognized Ratiman's role in helping develop small industries. In 1990, then-president Soeharto awarded him the Upakarti Award, a prize given to “successful figures” who have played a part in developing small industry.

His words of wisdom have gone around, too. Ichsanudin, author of the motivational book The Secret Business of Success, Smart Way to Make Money, quoted Ratiman’s saying: "I didn't have any education. I didn't have any money, so what else could I do besides working diligently?"

Agus Suparyanto, the chairman of Paguyuban Wonogiri Manunggal Sedya (Wonogiri Manunggal Sedya Association) told the Post that Ratiman was a “pioneer” and that his story had paved the way for people from Wonogiri to seek fortune in Jakarta as chicken noodle sellers.

Boyimin, a 49-year-old man, was also inspired by Ratiman's story of leaving Wonogiri for Jakarta. He began pushing his noodle cart around the Glodok area, just like Ratiman did, in 1994.

"Alhamdulillah, I moved here [to Jakarta] with nothing but intention, [recklessness] and a willingness to leave [home].”

Though he suffered through the financial crisis of the late 90s, Boyimin today owns four carts, operating around West and Central Jakarta. He has hired staff to help with his business.

He now lives in a three-story house in Kembangan, West Jakarta, with his wife and three children – a far cry from his early years in Jakarta, where he lived in a rented house with his brother.

"In Wonogiri, there is a motto: Success can be achieved," said Boyimin.

Tri often hears from the people her father has influenced and helped.

She beams with pride.

"Dad has created many jobs. Though he lacked education, he became a businessman. Alhamdulilah, I am proud to have a father like him," said Tri

--Additional reporting by Aryo Bhawono.