Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search results‘No’ to R2P procedural resolution: Principled stance against all odds

Historically, such coercive action conducted under the R2P largely depended on the resources and capacities of superpowers and their coalitions.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

T

his article is a response to Lina Alexander’s opinion piece “Indonesia and R2P: Why so paranoid?”, which was published in The Jakarta Post on May 22. We need to address the false logic that translates a vote against a procedural resolution on the responsibility to protect into doubt over Indonesia’s full commitment to abolishing genocide and crimes against humanity.

Lina’s central criticism seems to rest on the notion that “Indonesia cannot be in the same club with countries that have rejected R2P substantively due to their human rights record”. This assertion, and the mischaracterization of Indonesia’s vote, fail on many grounds, factual as much as substantial, and contains logical fallacies.

Why is this a false logic?

First, our “no” vote on a R2P procedural resolution is by no means equal to our steadfast support for the just implementation of R2P elements.

The resolution, presented by Croatia on May 18, was a “short and procedural draft” to just include R2P in the annual permanent agenda of the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA). Unfortunately, certain quarters deemed Indonesia’s voting position a refusal to engage in the discussion, even though, during the consultation of Croatia’s draft, Indonesia was actively engaged in the negotiations.

The discussion of R2P procedures on May 18 was neither the first nor a towering event in the history of the R2P’s development. Since 2009, the discussion on the R2P has become less attractive among states, with participation shrinking from 92 states (representing 180 states) to only 70 (representing 104 states) in 2019. Despite the decline, Indonesia actively and constructively contributed to the informal meeting annually.

In fact, Indonesia was among the parties voicing support for the R2P concept to be stipulated in the 2005 World Summit’s Outcome Document. We could have voted against it during the summit.

One of Lina’s misconceptions is partly triggered by an inability to distinguish and understand differences between the procedural and substantial UN agendas, as shown in the R2P voting. She could have been more precise by highlighting the divergent views evolving throughout the UNGA’s annual considerations on the R2P from 2009 onward.

Discussion to make R2P a permanent agenda point within the UNGA, therefore, is very different from and must be distinguished from any discussion over the substantive aspects of R2P. Based on this reality, our recent vote was a principled stance, where we disagree to prematurely making the R2P debate a permanent agenda item within the UNGA.

Second, Indonesia’s “no” vote, in fact, was based on our deep-founded view of the importance of guiding the discussions about R2P moving forward. It should not be oversimplified to claim that Indonesia’s position reflects its paranoia and inconsistency in its efforts to fight for humanity and human rights causes.

Since long ago, Indonesia’s reluctance to make R2P a permanent agenda point of the UNGA has lingered around cautiousness over the immature content of the R2P. At the very core, in 2005, states agreed to include R2P in the World Summit’s outcome, because we had faith in the genuine spirit of R2P to guide human rights and humanity. However, as the discussions developed, debates over its concept continued to be muddied – mixing up the need to prevent genocide, war crimes, ethnic cleansing and crimes against humanity with the tendencies to allow intervention in other sovereign states.

One may consider R2P a good instrument to ensure betterment of human rights and humanity across the world, but one should never be fully complacent. The first and second pillars of R2P are genuinely good in nature to encourage and support states in their efforts to protect human rights.

However, there remains the third pillar of R2P that allow states to intervene in other states – in the name of human rights, while at the very same time disregarding the eminence of respecting the local people’s dignity and rights.

Libya was the very first case of a “successful” R2P scenario playing out, in which 331,000 people found themselves in a humanitarian emergency, 100,000 people fled to neighboring countries and 287,000 people were internally displaced – after a military campaign under R2P flagship.

Historically, such coercive action conducted under the R2P largely depended on the resources and capacities of superpowers and their coalitions. Importantly, it is worrisome that R2P action is primarily aimed at weak states, while it is very unlikely be applied against powerful ones.

With this in mind, we have been consistent in our stance that the pillars of the R2P concept should be clarified before it enters the UN system as a permanent agenda point – which is political in nature. Before it enters the political battlefield, UN member states should fixate answers to the remaining questions on “selectivity”, who will conduct, how will it be conducted, when it should be conducted, and how to avoid the politicization of its use.

With these questions remining unresolved, many have warned that R2P is prone to be misused or misunderstood as a political justification for intervention, once it permanently enters the UN political arena.

Dominant states hastily intertwine the failure of prevention efforts with a need to implement more action-oriented policies; having early-action measures at their hands and disposal. More fundamental questions and proposals pertain to the issue of dragging so-called perpetrators to the International Criminal Court, a question of the accountability mechanisms that is hardly gaining consensus among UN member states.

With the current global humanitarian snapshots, such political action to endorse an unclear concept of R2P and its implementation is premature and dangerous. What if the argument for action is based on false grounds, such as in the case of the Iraq War?

Against this background, we have decided to stand our ground and express our view that discussion on the R2P should be maintained in a fair, constructive, unpoliticized and just manner before it eventually enters the UN system permanently.

Third, against all the dynamics behind the R2P procedural resolution, it is utmost valid for Indonesia to uphold its free and active foreign policy. Our position to suggest to all member states to have more patience in constructing a just and genuine R2P concept is based on our vision mandated by the Constitution.

R2P, as a future instrument to pursue world’s peace, should always be discussed in a productive way that is constructive to all states and that unites – rather than divides – the UN member states.

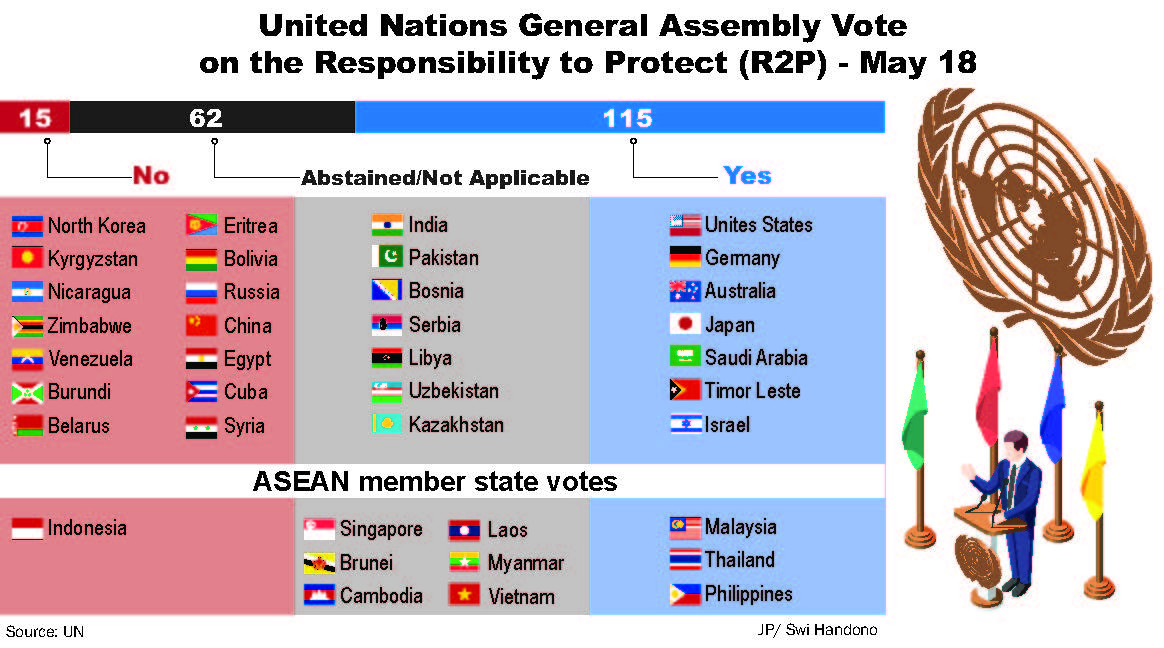

Therefore, one must not in an act of oversimplification misconstrue the 115 votes “in favor” as the absolute righteous vote of the UNGA. Among 193 member states of the United Nations, 78 remained unsure about the notion by voting “no”, “abstain”, or not voting at all. This shows that making R2P a permanent UNGA agenda item is anything but an issue producing consensus among member states – and it may be one causing division.

***

The writer is director for human rights and humanitarian affairs, Ministry of Foreign Affairs.