Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsShedding new light on Indonesia’s war of independence

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

A

n exhibition at Amsterdam’s Rijkmuseum uses posters, personal belongings and other objects exhibited for the first time to put a human face on Indonesia’s war of independence against the Dutch which lasted from 1945 to 1949.

Three young women walked down a street in Yogyakarta, the provisional capital of Indonesia during the country’s revolutionary war of independence against the Dutch. Dutch photographer Hugo Wilmar took a picture of the trio, who were members of the Service of Indonesian People from Sulawesi (KRIS) militia during the height of the conflict in December 1947, which he titled Three Young Indonesians on the Streets in Yogyakarta.

The trio’s stride reflected their confidence, while their carbines epitomized their determination to keep the country’s former colonial overlords from making a comeback.

Back in time: Three young Indonesians on the Streets in Yogyakarta, December 1947 by Hugo Wilmar. (Dutch National Archives/Spaarnestad Collection) (Dutch National Archives/Spaarnestad Collection)Putting a human face to the conflict

The photo is one of many taken of the conflict by photographers from around the world, among them legendary French photojournalist Henri Cartier-Bresson. “Often [the photographers] were thoroughly infatuated with the looks and swagger of the young Indonesian revolutionaries,” observed Amsterdam Rijksmuseum history curator Harm Stevens. “In their photos we see how an [extremely photogenic] Indonesian revolutionary self-image developed.”

The photo, which belongs to the Spaarnestad Collection of the National Archives of the Netherlands, is one of 230 objects shown at the Revolusi!: Indonesia Independent exhibition at Amsterdam’s Rijksmuseum until June 5. The event “explores subjects such as nationalism, youth, anti-colonialism, art, war and diplomacy, propaganda, renewal, the information war and refugees,” said the museum’s press release.

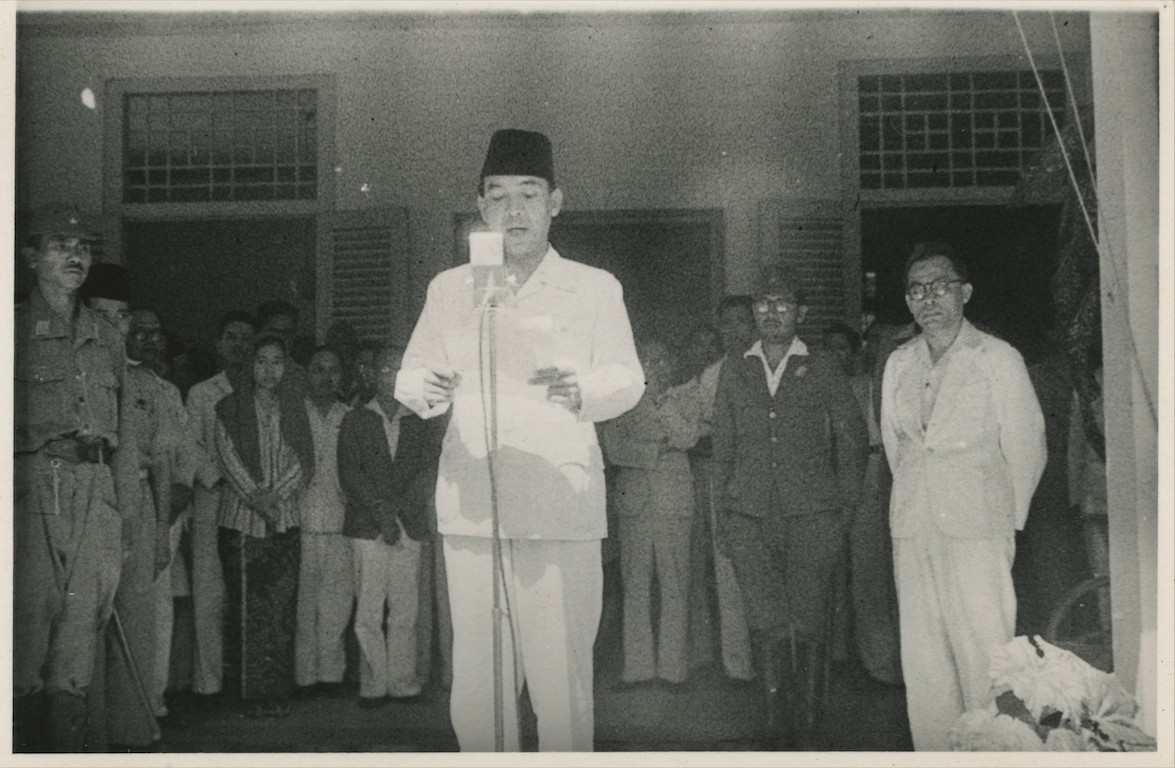

Curated by experts such as Indonesian historians Bonnie Triyana and Amir Sidharta, as well as their Dutch counterparts Harm Stevens and Marion Anker, Revolusi! started with Indonesian photojournalist Soemarto Frans Mendur’s Sukarno Reading the Text of the Proclamation, which depicted the Indonesian founding father and first president Sukarno declaring the country’s independence on August 17, 1945 in Jakarta. The exhibition ended with Cartier-Bresson’s photographs depicting Sukarno’s triumphant entry to the capital in 1949.

While Revolusi! touched on important events such as the Battle of Surabaya in November 1945 and the General Offensive on Yogyakarta in March 1949, the exhibition also highlighted other aspects of the struggle, such as the artistic renaissance inspired by the conflict. This surge in the arts ranged from painter Henk Ngantung’s firsthand observations of the Linggadjati Agreement to S. Sudjojono’s eclectic portrayal of Indonesian independence fighters. Most of all, the exhibition’s draw lies in personal objects of those caught up in the conflict.

“[Revolusi!] centers on the people in the revolusi: fighters, artists, diplomats, children, politicians, journalists and others […] via objects and eyewitness reports,” said Rijksmuseum general director Taco Dibbits of the event, which is the first of its kind in Europe. “The process of listening beyond the walls of the Rijksmuseum – the conversations with descendants of the people who went through the Indonesian revolution, and with historians and researchers in the Netherlands and Indonesia – brings the various points of view together.”

Fighting for the new nation

The role of the Indonesian Military (TNI) in securing Indonesia’s independence is seared in the collective memory of generations of Indonesians since 1945, not least through annual remembrances dating to that year such as Indonesia’s Independence Day on August 17 and Heroes Day on Nov. 10, which marks the Battle of Surabaya.

The hagiography of these events tends to obscure the role of servicemen such as Sutarso Nasrudin, a soldier who served with the TNI’s Siliwangi Division. He would have remained anonymous if not for a photo album captured by his Dutch foes. The black and white photos of himself, his comrades and their loved ones seemed to chronicle a young man growing up and making his way in a turbulent world. But a closer look dispelled that illusion.

“Nasrudin seems to have been conscious of the risk that the book and the identity of his friends might fall into the hands of the enemy, for the word pembakaran [burn] is written on the last pages,” Stevens said. “Whether this […] led to the arrest of the comrades of Nasrudin gathered in the book is unknown, but the possibility cannot be excluded.”

He left no doubts about Nasrudin’s fate. “The book’s cover bears a sticker, probably added years later, with the words "owner executed". Some words in pencil are still just visible under the sticker: "S. Nasrudin, executed by Capt. Janssen v E […]”

While Indonesian history texts might highlight the sacrifices of pribumi (indigenous people), such as unknown soldiers like Nasrudin, Indonesia’s first vice president and preeminent negotiator Mohammad Hatta and TNI commander General Sudirman, they overlooked the contributions of foreigners who embraced the nationalist cause. They include pioneering Indonesian diplomat and feminist icon Tanya Dezentje. Born into a family of Dutch and Indonesian descent, Dezentje broadcast radio messages advocating Indonesian independence to the outside world, before taking up the cause on the diplomatic front.

Unsurprisingly, the Dutch authorities did not think well of Dezentje. The Netherlands Forces Intelligence Service (NEFIS) described her as a “spy, collaborator, exotic figure […] belonging to the category of dangerous women.”

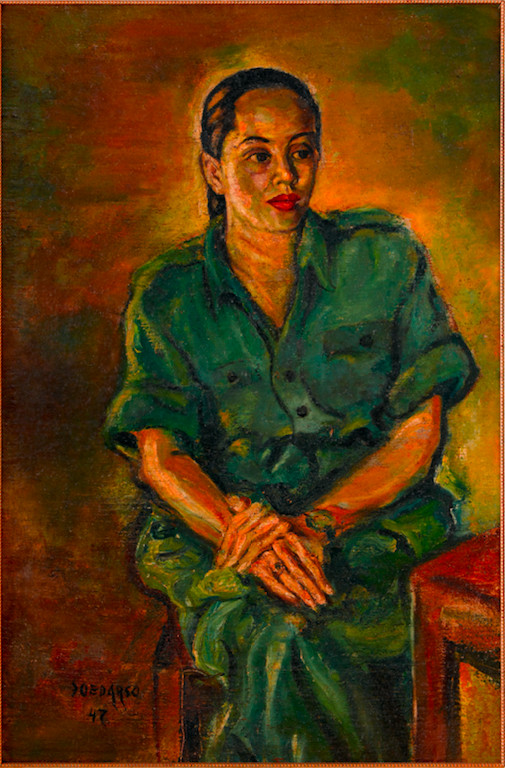

On display: A portrait of Tanja Dezentjé, 1947 by Sudarso. (Courtesy of Christin Kam) (Courtesy of Christin Kam/Courtesy of Christin Kam)On the other hand, Indonesian painter Sudarso’s portrait of Dezentje in military uniform showed her respected status among Indonesian revolutionaries. Painted in 1947, the work reflected her standing as a prominent figure in Indonesia’s Foreign Ministry and the country’s branch of the Red Cross. Dezentje’s life reflected the divided loyalties among Eurasians and other minorities, which contrasted her experiences with compatriot Jeanne van Leur de Loos and Letty Kwee.

Chronicles of displacement

While the Indonesian National Revolution symbolized a new era for Indonesians yearning for independence, the upheaval meant displacement for hundreds of thousands of Dutch nationals, Eurasians and members of Indonesian ethnic minorities deemed to collaborate with the Dutch. They include Jeanne "Peu" van Leur de Loos, who settled in Indonesia for years and was interned for more than three years by the Japanese after their takeover in 1942.

Like her compatriots and others fleeing the conflict, Peu returned to a land she barely knew with a few possessions, among them a handsewn house dress. Made from silk issued to British Royal Air Force crewmen, the outfit looks like an item sold by Banana Republic. But the dress perhaps chronicles her chaotic last days in Indonesia.

Gowns: Housecoat of silk maps, Jakarta 1945 by J. Terwen-de Loos, at Rijkmuseum, Amsterdam. (Courtesy of Rijkmuseum) (Courtesy of Rijkmuseum/Courtesy of Rijkmuseum)“Peu’s gown was composed of maps of […] ’Burma’, ‘French IndoChina’, ‘Siam’ [...] The escape map may have found, their way, probably via British soldiers, to one of the many passars [sic] [traditional markets] in Jakarta,” noted Stevens and Marion Anker. “Peu, possibly with the help of a middleman, must have bought a stack of [the maps in markets] […] Westerners have not been welcomed in tokos [stores] and passars for some time.”

Peu fled to the Netherlands during the Bersiap (be ready) phase of the conflict that lasted from October 1945 to early 1946. The period was marked by the killing of Dutch citizens, Eurasians and minorities who did not flee their colonial home in time.

Another refugee fleeing from the strife surrounding the Bersiap period of Indonesia’s war of independence was Laetitia "Letty" Kwee, who fled from Jakarta with her family in 1946. A member of a Chinese mercantile family with close ties to the Dutch colonial administration, Letty’s experience was similar to Chinese Indonesians who experienced the May 1998 riots more than 50 years later.

“The [Bersiap] violence was visible in broad daylight […] as shown by footage of the Molenvliet canal […] not far from the Kwee family home,” Stevens noted. “A man’s corpse floats by, carried by the canal’s slow current. The camera then swings upward towards the quay, where passersby […] observe the gruesome scene.” Stevens estimated that over 10,000 Chinese-Indonesians were killed by both sides during the war.

Leyden University academic Remco Raben estimated that the “number of victims in the Dutch and Eurasian population [during Bersiap] is unknown, but a realistic estimate would be around 5,500,” he observed. “Other groups associated with the colonial regime were also among the victims, such as the Chinese, the Ambonese and the former governing aristocracy.”

This phase of the Indonesian war of independence continues to strike a raw nerve with some in the Dutch public, as an organization called the Federation of Dutch Indonesians took legal action against the organizers of the Revolusi! exhibition for their views on the Bersiap period. Nonetheless, the Dutch Justice Ministry chose not to proceed with the case.

Dibbits hoped to “build on the good international working relationships” between Indonesian and Dutch experts who worked on the Revolusi!: Indonesia Independent exhibition, which runs until June 5. Whether his vision will come about or not remains to be seen. Until then, drop by to get these personal glimpses of the Indonesian war of independence that is not found in Dutch or Indonesian history books.