Popular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsPopular Reads

Top Results

Can't find what you're looking for?

View all search resultsWhat I’ve Learned: Jessica Washington, journalist

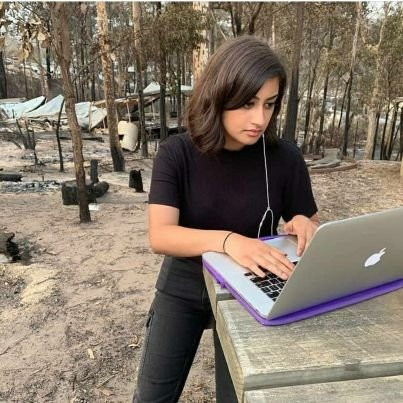

Al Jazeera’s Jessica Washington has reported everything from the measles outbreak in Samoa, the 2019 bushfires in Australia, the COVID-19 situation in Indonesia, and the Kanjuruhan stadium disaster.

Change text size

Gift Premium Articles

to Anyone

A

l Jazeera’s Jessica Washington lives and breathes the news. The Jakarta-based correspondent has reported on the measles outbreak in Samoa, the 2019 bushfires in Australia, the COVID-19 situation in Indonesia, the Kanjuruhan Stadium disaster, as well as various natural disasters. She joined Al Jazeera in 2019.

Today we talk with Jes about whether she sees reporting as a form of activism, what it is like to cover a tragedy on the ground in real time, and why she remembers everyone she has ever interviewed.

Journalists see situations and people in some dark times, and they approach us with the mindset that asks what we can contribute to a situation. I don’t know if that is activism so much as an amplification of voices.

We as international media can broadcast those voices. There are already activists out there, trying to make changes in their communities. International media can be a platform for discussing those issues in a nuanced way, and amplifying voices.

When we are covering a tragedy, we are likely meeting people on the worst day of their lives, and I am always aware of that. I like to approach things with this question in mind: “If this were my family, how would I want them to be treated?”

My role is to give a full picture of light and shade. Sometimes there are tragedies, yes. But it is the responsibility of journalists to show a balanced picture of what life is like here. It’s important to me to cover things that are beautiful, positive and meaningful, not just disasters. One of my favorite assignments last year was going to Miduana village in Cianjur, where we met residents who claim to live unusually long lives. They were seniors, who were extremely keen to show me their silat (martial arts) skills, and share their secrets to living a long, happy life. I had a lot of fun with that story.

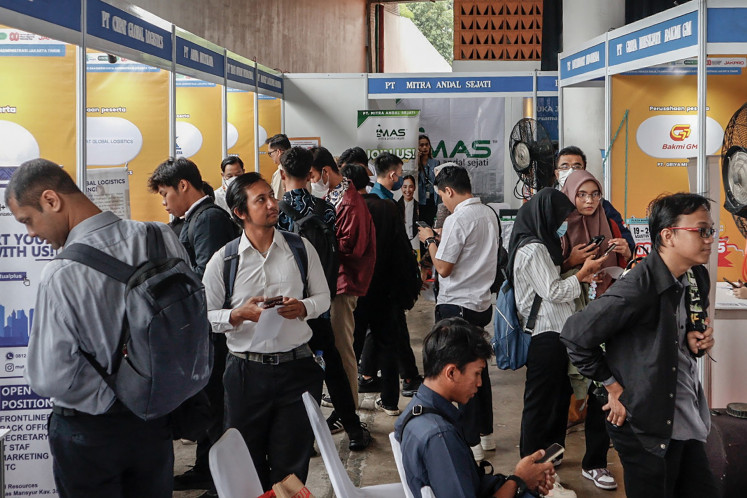

People do want to talk. When I think of the football stadium tragedy people were coming to us and saying “I was there that night. I want to tell you about my friend. I want to tell you what I saw.” They are keen to get some form of justice and we are a mechanism for that.

People are usually keen to seize the opportunity to share with the world a story about a person they love and now the world can remember them with them. There’s a difference between exploiting a tragedy and covering a story.

I’m quite an emotional person. I remember everyone we’ve met and spoken to.

When I was still a student one of my professors asked the class “What is the most important story you’ve ever worked on?” And everyone in the class was sitting there trying to think of an impressive way to respond. And he said, “The answer should be ‘the one I’m working on today’.”

You owe that to the people in your stories, the interviewees, they are front-and-center in your mind. I always try to remember that.

We are there to listen. Journalism is 90 percent listening. When I started, I was worried because I am quite quiet […] I don’t really have an outgoing personality. But it turns out that most of the job is listening. People just want someone to listen to their story and what has happened to them.

I think audiences will find news where they might already be. In Indonesia TikTok is one of the main sources of news, especially for young people. I don't think that’s necessarily a bad thing.

I think traditional news organizations have to think “Where can I meet people? And can I meet them where they already are?”

I’ve learned that it’s extremely hard to make predictions. You never know what’s going to happen here. And there’s still a lot of time before 2024.

As a reporter you are building nuance. It’s fine to talk about the potential of Indonesia, but your job as the reporter is to paint a more nuanced picture, showing the avenues for potential and the amazing things already being done on the ground.

I was recently speaking with some journalism students at a university, and I find that increasingly the new generation of journalists are thinking about mental health and physical health. I think it’s admirable that they have these questions, even before they start working as journalists.

You need to take a break from that 24-hour news cycle. So, time-off means time-off. But sometimes on a day off people are sending messages “Did you see this article? Did you see that article?” but I think it is important for everyone, not just journalists, to switch off if possible.

***

What I’ve Learned is a new column that presents candid interviews with policymakers, artists, activists and businesspeople on facing challenges and making a difference.